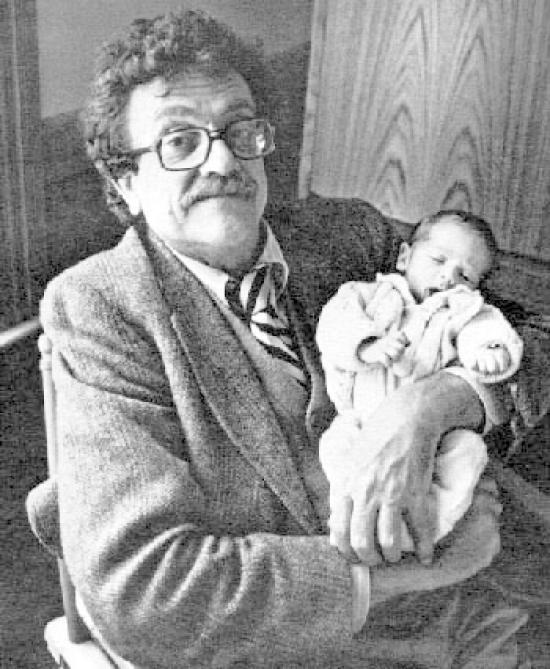

Kurt Vonnegut, who was pained by the inequalities of life–both the natural and man-made varieties–raises the specter of mass extinction during a 2005 interview with Jon Stewart.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Books category.

Tags: Jon Stewart, Kurt Vonnegut

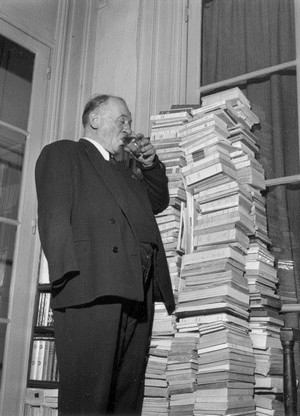

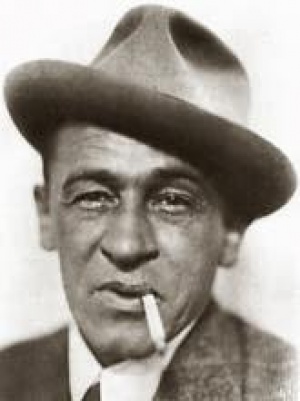

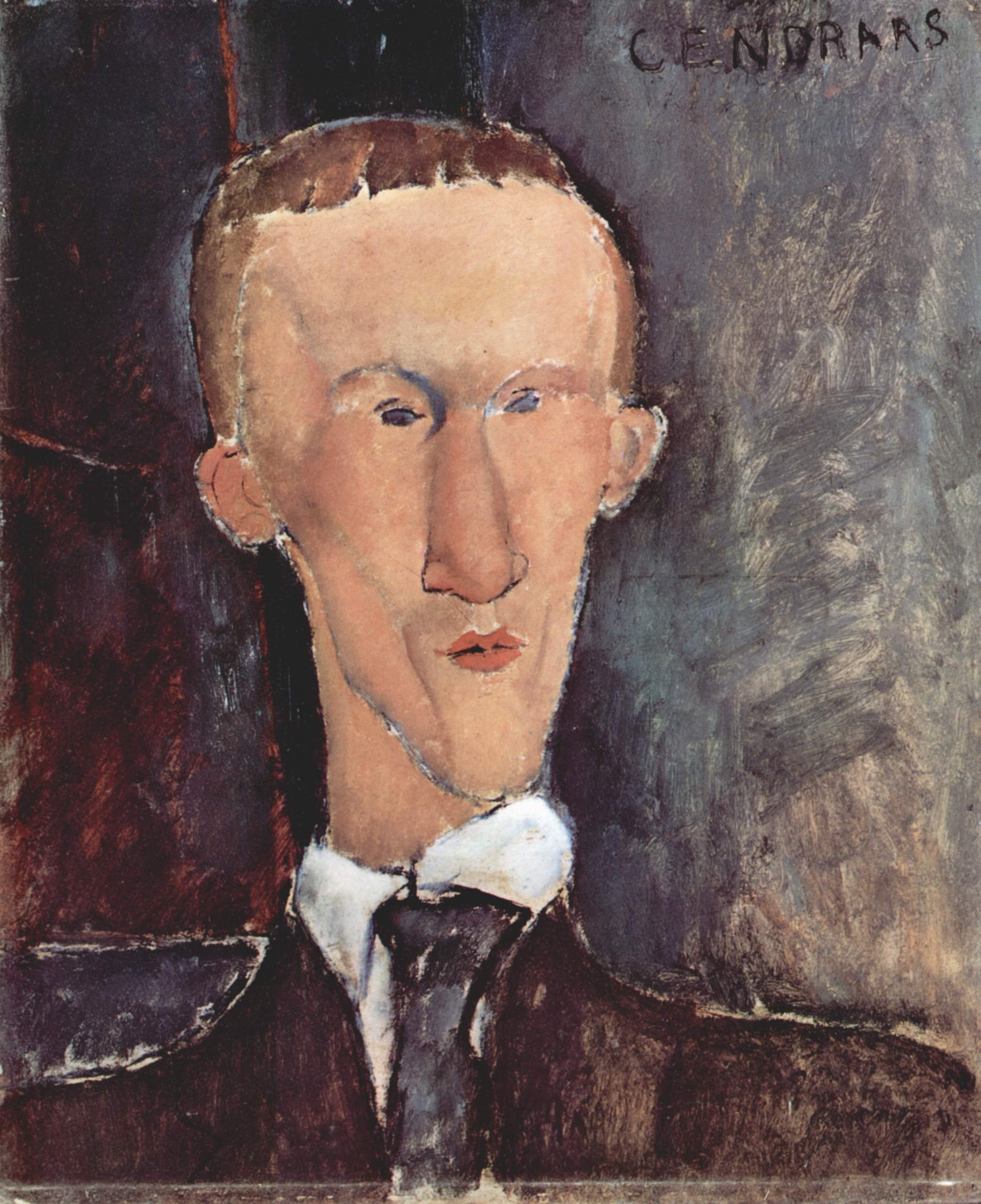

That wonderful Luc Sante contributes brief descriptions of his creative heroes to the HiLoBrow site. Click on any of the links below to read them. And see an example, a piece about Blaise Cendrars, below.

Dashiell Hammett | Pancho Villa | James M. Cain | Georges Bataille |Félix Fénéon | Émile Henry | A.J. Liebling | Jim Thompson | Joe Hill | Nestor Makhno | Hans Magnus Enzensberger | Captain Beefheart | William Burroughs | Ring Lardner | Lee “Scratch” Perry | Serge Gainsbourg | Kathy Acker | Arthur Cravan | Weegee | Alexander Trocchi | Ronnie Biggs | George Ade |Georges Darien | Zo d’Axa | Petrus Borel | Blaise Cendrars | Alexandre Jacob | Constance Rourke | Damia |J-P Manchette | Jean-Paul Clebert | Pierre Mac Orlan | Comte De Lautreamont | Robert Desnos | Arthur Rimbaud |

“BLAISE CENDRARS (Frédéric Sauser, 1887-1961) was five writers in succession. First he was a poet, whose ‘Prose of the Transsiberian’ (1913) was the first to apply Cubist principles of cut-up and simultaneity to verse, and whose Kodak (retitled Documentaires at the insistence of the Eastman Co.; 1923) was much later shown to have been extracted line by line from Gustave Le Rouge’s science-fiction epic The Mysterious Doctor Cornelius. Then he was a screenwriter and sometime director, best known for his work on Abel Gance’s J’Accuse (1919) and La Roue (1923). After that he was the author of novels that run the gamut from a kind of cinematic documentary montage (Sutter’s Gold, 1925) to hallucinatory yarns that suggest Jules Verne on laudanum (Moravagine, 1926; Dan Yack, 1927). He shone as an imaginative reporter in the 1930s, investigating crime, Hollywood, and the beginnings of World War II in a series of lapidary works that haven’t been translated into English. Finally he was a memoirist of an unusual sort, mixing up time and place in favor of subjective or perhaps cubistic recall, as in The Astonished Man (1945) and Planus (1948). He alternated all his life between wild flights of language and pellucid visual and factual description, consciously constructing parallels between literature and film, photography, and painting. He had a face that looked like it was bashed out of granite, in a corner of which lived a perpetually smoldering hand-rolled cigarette butt. He lost an arm at the Navarin Farm offensive in the Champagne, 1915, and always made a point of displaying his empty sleeve.”

Tags: Blaise Cendrars, Luc Sante

I’ve written before that I don’t think it’s clear how we reconcile an automated society and a capitalist one. We managed to reinvent work in America during the Industrial Revolution by throwing ourselves into new information businesses (marketing, public relations, advertising, etc.). Perhaps such alternatives will emerge again. If not, we need to reconfigure our economic model, maintaining free markets but sharing the wealth somehow. Otherwise inequality will reach traumatic levels. At the New Yorker blog, Joshua Rothman interviews Tyler Cowen about these issues and others. I have questions about Cowen’s vision of America’s future, but he always makes intelligent points. The interview’s opening:

“Question:

In Average Is Over, you argue that inequality will grow in the U.S. for the next several decades. Why?

Tyler Cowen:

There are three main reasons inequality is here to stay, and will likely grow. The first is just measurement of worker value. We’re doing a lot to measure what workers are contributing to businesses, and, when you do that, very often you end up paying some people less and other people more. The second is automation—especially in terms of smart software. Today’s workplaces are often more complicated than, say, a factory for General Motors was in 1962. They require higher skills. People who have those skills are very often doing extremely well, but a lot of people don’t have them, and that increases inequality. And the third point is globalization. There’s a lot more unskilled labor in the world, and that creates downward pressure on unskilled labor in the United States. On the global level, inequality is down dramatically—we shouldn’t forget that. But within each country, or almost every country, inequality is up.

Question:

You think that intelligent software, especially, will make the labor market more unequal. Why is that the case?

Tyler Cowen:

Because of the cognitive requirements of working with smart software. And it’s also about training. There’s a big digital divide in this country.”

Tags: Joshua Rothman, Tyler Cowen

I don’t pay attention to a lot of celebrity news, but I believe a new book recently revealed that Johnny Carson used to do the Tonight Show monologue with a loaded gun stashed in his underpants. Good for him. In 1994, Johnny, now in retirement and a little heavier, made a wordless appearance with David Letterman (after a brief Larry “Bud” Melman fake-out). Carson would never turn up again on television, falling into a complete silence. Letterman still gave a crap at this point. I always try to pinpoint when he exactly stopped caring, and I think it was 1998 or thereabouts. Still a great interviewer, though.

Tags: David Letterman, Johnny Carson

Paper will survive the Digital Age, but publishing will never be the same business again. From Carolyn Kellogg at the L.A. Times:

“Ninety-eight British publishers closed their doors in the year ending August 2013. The cause? E-books and online discounts.

Closures were up 42% over the previous year, according to the Guardian. The companies that folded included the 26-year-old healthcare publisher Panos London, and Evans Brothers, which published popular children’s book author Enid Blyton for 30 years.

During 2012, e-book sales in Britain rose by 134% to more than $346 million. While print sales still dominate the bottom line in Britain with more than $4.6 billion in sales, that total was a 1% drop from the year before. The trend is toward e-books, and that trend has not been good for publishers.”

Tags: Carolyn Kellogg

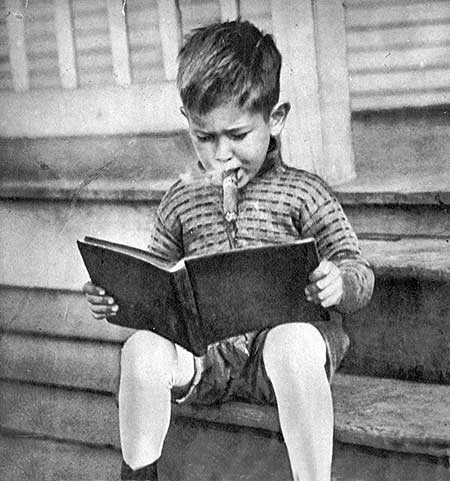

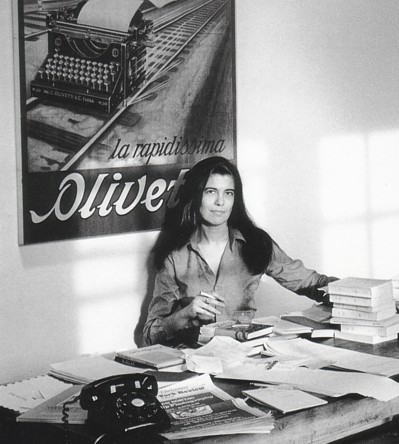

The 1978 Rolling Stone interview of Susan Sontag by Jonathan Cott has just been published in unexpurgated book form. Her short-story collection, I, Etcetera, was released the same year that the Q&A was conducted, and sometimes for no reason I find myself thinking about the selection “Baby,” wondering how much of who we are comes from the time we’re born into. How much can we resist?

From Mark O’Connell’s Slate piece about the RS book:

“Intense seriousness, of course, always has a tendency to verge on the comic. Sontag was the Platonic ideal of the intellectual, and so she could also come across as a not-too-subtle parody of the very idea of such a person. At one point, she tells Cott that the first book that really thrilled her was a biography of Marie Curie by Curie’s daughter Eve, which she recalls reading at age 6. The interviewer is impressed that a child of that age would go in for material of such relative heft. ‘I started reading when I was 3,’ she expands, ‘and the first novel that affected me was Les Misérables—I cried and sobbed and wailed. When you’re a reading child, you just read the books that are around the house. When I was about 13, it was Mann and Joyce and Eliot and Kafka and Gide—mostly Europeans. I didn’t discover American literature until much later.’ What to do with such a claim but both laugh at it and marvel at it? I thought of how my mother likes to remind me of my own alleged precocity by mentioning how she once came across me, age about 5, peering into a Jeffrey Archer blockbuster as though it contained the secret of life. By that age, Sontag would have been rolling up her sleeves and getting into Cervantes.

But this long and largely genial portrait of the (not always quite so genial) intellectual in middle age also amounts to a strong and deeply personal argument about what it means to be cultured—an argument for why a middle-aged intellectual might be something worth being in the first place.”

Tags: Jonathan Cott, Susan Sontag

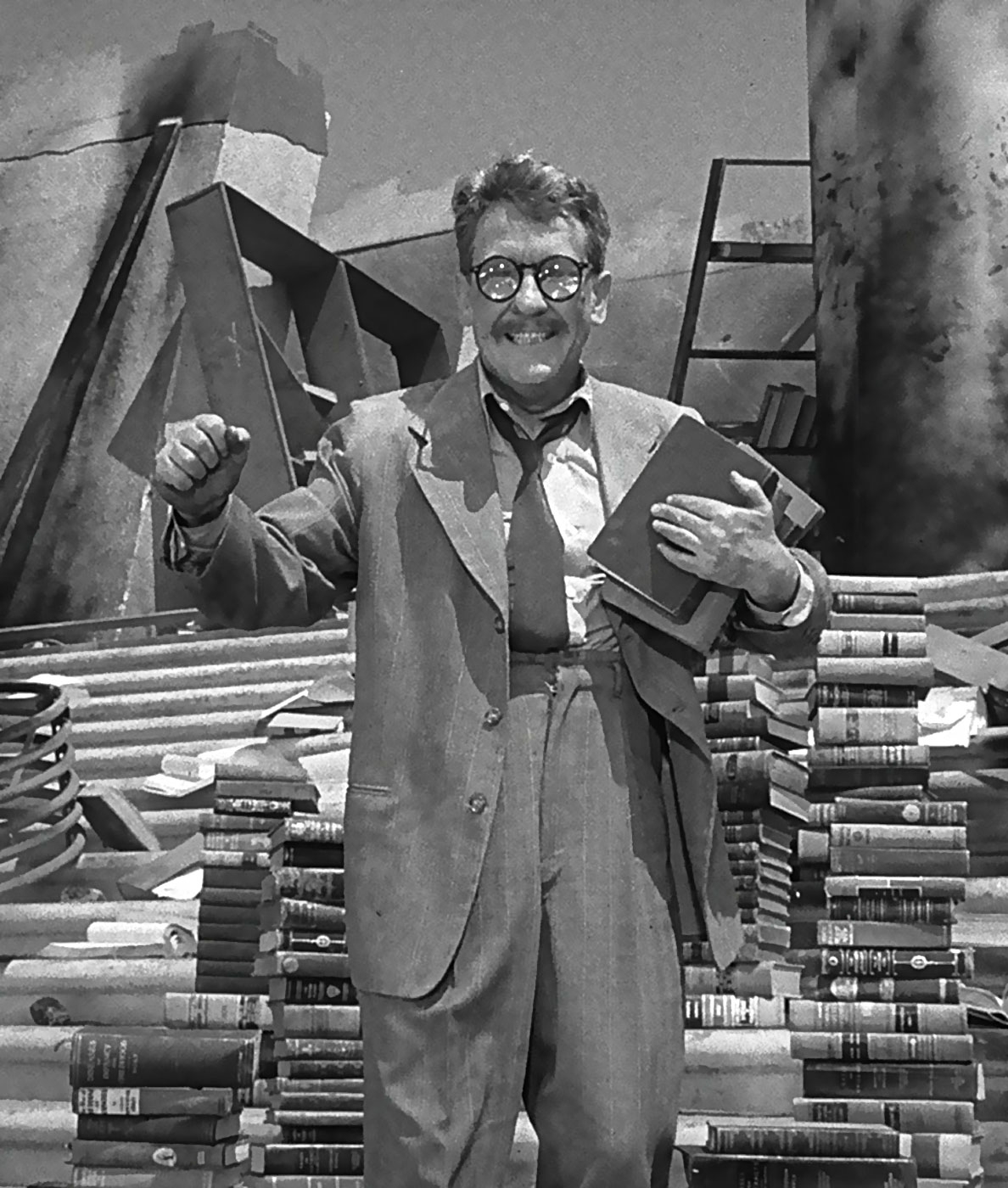

Some more predictions from Norman Mailer’s 1970 Space Age reportage, Of a Fire on the Moon, which have come to fruition even without the aid of moon crystals:

“Thus the perspective of space factories returning the new imperialists of space a profit was now near to the reach of technology. Forget about diamonds! The value of crystals grown in space was incalculable: gravity would not be pulling on the crystal structure as it grew, so the molecule would line up in lattices free of shift or sheer. Such a perfect latticework would serve to carry messages for a perfect computer. Computers the size of a package of cigarettes would then be able to do the work of present computers the size of a trunk. So the mind could race ahead to see computers programming go-to-school routes in the nose of every kiddie car–the paranoid mind could see crystal transmitters sewn into the rump of ever juvenile delinquent–doubtless, everybody would be easier to monitor. Big Brother could get superseded by Moon Brother–the major monitor of them all might yet be sunk in a shaft on the back face of the lunar sphere.”

Tags: Norman Mailer

There are fewer postcards and hand-written notes today, but I don’t think anyone would argue against the idea that more people in the world are writing more in the Internet Age than at any moment in history. What we’re writing is largely bullshit, sure, but not all of it is. It’s really the full flowering of democracy, like it or not. From Walter Isaacson’s New York Times review of Clive Thompson’s glass-half-full tech book, Smarter Than You Think:

“Thompson also celebrates the fact that digital tools and networks are allowing us to share ideas with others as never before. It’s easy (and not altogether incorrect) to denigrate much of the blathering that occurs each day in blogs and tweets. But that misses a more significant phenomenon: the type of people who 50 years ago were likely to be sitting immobile in front of television sets all evening are now expressing their ideas, tailoring them for public consumption and getting feedback. This change is a cause for derision among intellectual sophisticates partly because they (we) have not noticed what a social transformation it represents. ‘Before the Internet came along, most people rarely wrote anything at all for pleasure or intellectual satisfaction after graduating from high school or college,’ Thompson notes. ‘This is something that’s particularly hard to grasp for professionals whose jobs require incessant writing, like academics, journalists, lawyers or marketers. For them, the act of writing and hashing out your ideas seems commonplace. But until the late 1990s, this simply wasn’t true of the average nonliterary person.'”

Tags: Clive Thompson, Walter Isaacson

A paragraph from Margaret Atwood’s New York Review of Books’ review of Dave Eggers’ The Circle about the malignant undercurrent of technotopia:

“Some will call The Circle a ‘dystopia,’ but there’s no sadistic slave-whipping tyranny on view in this imaginary America: indeed, much energy is expended on world betterment by its earnest denizens. Plagues are not raging, nor is the planet blowing up or even warming noticeably. Instead we are in the green and pleasant land of a satirical utopia for our times, where recycling and organics abound, people keep saying how much they like each another, and the brave new world of virtual sharing and caring breeds monsters.”

Tags: Dave Eggers, Margaret Atwood

When he wrote about the coming computer revolution of the 1970s at the outset of the decade in Of a Fire on the Moon, Norman Mailer couldn’t have known that the dropouts and the rebels would be leading the charge. An excerpt of his somewhat nightmarish view of our technological future, some parts of which came true and some still in the offing:

“Now they asked him what he thought of the Seventies. He did not know. He thought of the Seventies and a blank like the windowless walls of the computer city came over his vision. When he conducted interviews with himself on the subject it was not a despair he felt, or fear–it was anesthesia. He had no intimations of what was to come, and that was conceivably worse than any sentiment of dread, for a sense of the future, no matter how melancholy, was preferable to none–it spoke of some sense of the continuation in the projects of one’s life. He was adrift. If he tried to conceive of a likely perspective in the decade before him, he saw not one structure to society but two: if the social world did not break down into revolutions and counterrevolutions, into police and military rules of order with sabotage, guerrilla war and enclaves of resistance, if none of this occurred, then there certainly would be a society of reason, but its reason would be the logic of the computer. In that society, legally accepted drugs would become necessary for accelerated cerebration, there would be inchings toward nuclear installation, a monotony of architectures, a pollution of nature which would arouse technologies of decontamination odious as deodorants, and transplanted hearts monitored like spaceships–the patients might be obliged to live in a compound reminiscent of a Mission Control Center where technicians could monitor on consoles the beatings of a thousand transplanted hearts. But in the society of computer-logic, the atmosphere would obviously be plastic, air-conditioned, sealed in bubble-domes below the smog, a prelude to living on space stations. People would die in such societies like fish expiring on a vinyl floor. So of course there would be another society, an irrational society of dropouts, the saintly, the mad, the militant and the young. There the art of the absurd would reign in defiance against the computer.”

Tags: Norman Mailer

A very raw Rolling Stones performance of “Sympathy for the Devil” on a David Frost show in 1968. I’ve never read any books about the Stones so I always wondered if this song was inspired by Rasputin’s legend or if Mick Jagger had read Blaise Cendrars’ novel Moravagine, which has a similar storyline. But it actually sprang from Baudelaire and Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. I’m definitely in the minority, but I like Moravagine more than The Master and Margarita. The former cuts me to the core.

Tags: David Frost, Mick Jagger, The Rolling Stones

Google is chiefly interested in accurately answering your requests because your questions have monetary potential, with predictive powers labeling you someone who likely is (or likely to become) a vegan or a yoga enthusiast, or, perhaps, a criminal. And so much the better if Big Data can figure this out before your first salad or downward dog or burglary. You aren’t just what you do but what the algorithms say you are likely to do. So, now, questions are treated like answers. From Sue Halpern in the New York Review of Books:

“The social Web celebrated, rewarded, routinized, and normalized this kind of living out loud, all the while anesthetizing many of its participants. Although they likely knew that these disclosures were funding the new information economy, they didn’t especially care. As John Naughton points out in his sleek history From Gutenberg to Zuckerberg: What You Really Need to Know About the Internet:

Everything you do in cyberspace leaves a trail, including the ‘clickstream’ that represents the list of websites you have visited, and anyone who has access to that trail will get to know an awful lot about you. They’ll have a pretty good idea, for example, of who your friends are, what your interests are (including your political views if you express them through online activity), what you like doing online, what you download, read, buy and sell.

In other words, you are not only what you eat, you are what you are thinking about eating, and where you’ve eaten, and what you think about what you ate, and who you ate it with, and what you did after dinner and before dinner and if you’ll go back to that restaurant or use that recipe again and if you are dieting and considering buying a Wi-Fi bathroom scale or getting bariatric surgery—and you are all these things not only to yourself but to any number of other people, including neighbors, colleagues, friends, marketers, and National Security Agency contractors, to name just a few.”

Tags: John Naughton, Sue Halpern

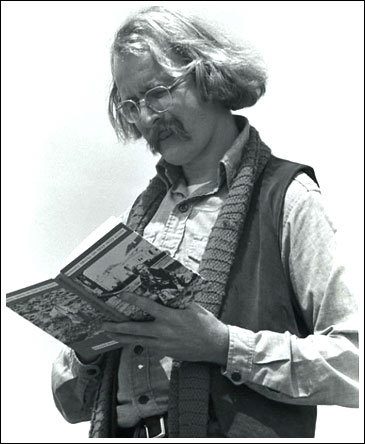

Richard Brautigan, who died in 1984 despite being all watched over by machines of loving grace, in interviewed a year before his passing on German TV.

Tags: Richard Brautigan

In his speculative 1974 novel, Ecotopia, Ernest Callenbach imagined an America disrupted by a West Coast secession led by environmentalists. Stanford’s Balaji Srinivasan has a different dream: a techno-utopia built in the aftermath of a Silicon Valley exit. Sounds terrifying. Google’s Larry Page has actually offered a soft-core version previously, suggesting we create physical space for conducting experimentation that is beyond laws or regulation. Equally scary. From Nick Statt at Cnet:

“Cupertino, Calif. — Balaji Srinivasan opened his Y Combinator startup school talk with a joke: Is the US the Microsoft of nations? The question was received warmly by the crowd of more than 1,700 and did in fact have a logical conclusion: Larry Page and Sergey Brin, co-founders of Google, were exactly what Bill Gates feared when he said in 1998 that two people in a garage working on something new was Microsoft’s biggest threat.

What ties those two seams together? The idea of techno-utopian spaces — new countries even — that could operate beyond the bureaucracy and inefficiency of government. It’s a decision that hinges on exiting the current system, as Srinivasan terms it from the realm of political science, instead of using one’s voice to reform from within, the very way Page and Brin decided to found their search giant instead of seek out ways in which the then-current tech titans could solve new problems.

Calling his radical-sounding proposal ‘Silicon Valley’s Ultimate Exit,’ Srinivasan thinks that these limitless spaces, popularly postulated by Page at this year’s Google I/O, are already being created, thanks to technology and a desire to exit. Ultimately, the Stanford lecturer and co-founder of Counsyl, a genetics startup, thinks Silicon Valley could lead the charge in exiting en masse because, eventually, ‘they are going to try and blame the economy on Silicon Valley.'”

Tags: Balaji Srinivasan, Larry Page, Nick Statt

Two videos of that wonderful Harpo Marx, the first comedian I adored. The initial one is a 1958 Person to Person “interview” a studio-bound Edward R. Murrow conducted via long distance with the mute comic and his talkative family in their Palm Springs home. The second is a 1961 appearance on the Today show to promote the release of his now-classic biography, Harpo Speaks!

Tags: Harpo Marx

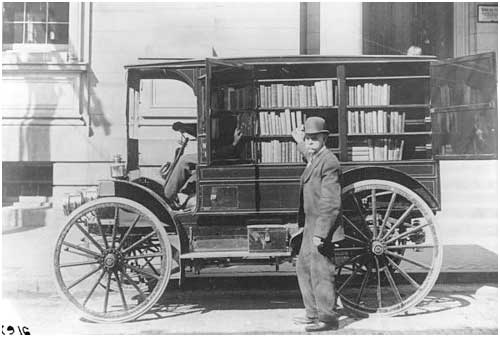

Even though it wasn’t particularly cost-efficient, early airplanes (or “aeroplanes”) were sometimes utilized to deliver newspapers. While physical textbooks are a questionable commodity in an age when the Encyclopedia Britannica can be put on the head of a pin, an Australian company is using drones to deliver them. From Emily Keeler in the Los Angeles Times:

“Imagine the book you need to ace the exam showing up at your door, care of your friendly neighborhood drone.

A textbook rental company is trying to mimic the instantaneous speed of e-book delivery for printed books by utilizing civil drones in Sydney, Australia. Zookal, a service that rents textbooks to university students, has partnered with Flirtey, an outfit specializing in unmanned aerial vehicles, to aerially deliver print books to customers within minutes after an order is placed.

The Age reports that the service uses the GPS coordinates of a user’s smartphone to make textbook deliveries, a win for cramming students who have left studying to the very last minute and and need to save all the time they can. After one of six Sydney drones has been dispatched, students will be able to track the realtime journey of their unmanned textbooks on a Google-powered map.”

Tags: Emily Keeler

There’s now a large industry of writers and speakers telling you bullshit narratives about how you can think counter-intuitively, how you can see hidden patterns if you look through their eyes, how you too can become a creative thinker. Maddeningly, many of them do it supposedly supported by science and math. Taking aim with a cash register (just a Square is necessary, really) at the creative mind during the the dying days of the Industrial Revolution might be a good business model, but that doesn’t make it useful. From “TED Talks Are Lying to You,” Thomas Frank’s Salon essay about the sad state of the creative class and the lacking literature aimed at it:

“Those who urge us to ‘think different,’ in other words, almost never do so themselves. Year after year, new installments in this unchanging genre are produced and consumed. Creativity, they all tell us, is too important to be left to the creative. Our prosperity depends on it. And by dint of careful study and the hardest science — by, say, sliding a jazz pianist’s head into an MRI machine — we can crack the code of creativity and unleash its moneymaking power.

That was the ultimate lesson. That’s where the music, the theology, the physics and the ethereal water lilies were meant to direct us. Our correspondent could think of no books that tried to work the equation the other way around — holding up the invention of air conditioning or Velcro as a model for a jazz trumpeter trying to work out his solo.

And why was this worth noticing? Well, for one thing, because we’re talking about the literature of creativity, for Pete’s sake. If there is a non-fiction genre from which you have a right to expect clever prose and uncanny insight, it should be this one. So why is it so utterly consumed by formula and repetition?

What our correspondent realized, in that flash of bathtub-generated insight, was that this literature isn’t about creativity in the first place. While it reiterates a handful of well-known tales — the favorite pop stars, the favorite artists, the favorite branding successes — it routinely ignores other creative milestones that loom large in the history of human civilization. After all, some of the most consistent innovators of the modern era have also been among its biggest monsters. He thought back, in particular, to the diabolical creativity of Nazi Germany, which was the first country to use ballistic missiles, jet fighter planes, assault rifles and countless other weapons. And yet nobody wanted to add Peenemünde, where the Germans developed the V-2 rocket during the 1940s, to the glorious list of creative hothouses that includes Periclean Athens, Renaissance Florence, Belle Époque Paris and latter-day Austin, Texas. How much easier to tell us, one more time, how jazz bands work, how someone came up with the idea for the Slinky, or what shade of paint, when applied to the walls of your office, is most conducive to originality.”

Tags: Thomas Frank

In the end matter of a New York Times profile of Johnny Knoxville’s bruised, aging balls, I read this:

“Dave Itzkoff is a reporter at The Times. His book, Mad as Hell, about the making of the movie Network, will be published in February.”

This news is exciting because of my feelings for that film, arguably America’s best film satire, and because Itzkoff is such a good reporter and graceful writer, one of the few journalists who can interest me in reading about popular culture. The following video is one I’ve previously posted in which Paddy Chayefsky appears on a talk show in the 1970s to discuss Network and the coming global, technocratic, interconnected culture.

____________________________

Paddy Chayefsky, that brilliant satirist, holding forth spectacularly on the Mike Douglas Show in 1969. It starts with polite chatter about the success of his script for Marty but quickly transitions into a much more serious and futuristic discussion. The writer is full of doom and gloom, of course, during the tumult of the Vietnam Era; his best-case scenario for humankind to live more peacefully is a computer-friendly “new society” that yields to globalization and technocracy, one in which citizens are merely producers and consumers, free of nationalism and disparate identity. Well, some of that came true. All the while, he wears a fun, red lei because one of his fellow guests is Hawaii Five-0 star Jack Lord. Gwen Verdon, Lionel Hampton and Cy Coleman share the panel.

Chayefsky joins the show at the 7:45 mark.

Tags: Dave Itzkoff, Paddy Chayefsky

A couple of excerpts from a very entertaining New Republic interview that Laura Bennett conducted with literary agent Andrew Wylie, who disdains popular fiction, Amazon and most of the American public.

___________________________

Laura Bennett:

Do you feel as hostile toward Amazon as you used to?

Andrew Wylie:

I think that Napoleon was a terrific guy before he started crossing national borders. Over the course of time, his temperament changed, and his behavior was insensitive to the nations he occupied.

Through greed—which it sees differently, as technological development and efficiency for the customer and low price, all that—[Amazon] has walked itself into the position of thinking that it can thrive without the assistance of anyone else. That is megalomania.

Laura Bennett:

That sounds different from the attitude you had in 2010.

Andrew Wylie:

I didn’t think that [in 2010] the publishing community had properly assessed—particularly in regard to its obligations to writers—what an equitable arrangement would look like.

And I felt that publishers had made a huge mistake, because they were pressured by Apple and Amazon to make concessions that they shouldn’t have made.

These distribution issues come and go. It wasn’t so long ago that Barnes and Noble was this monster publishing leatherette classics, threatening to put backlists out of print. Amazon will go, and Apple will go, and it’ll all go.

I think we’d be fine if publishers just withdrew their product [from Amazon], frankly. If the terms are unsatisfactory, why continue to do business? You think you’re going to lose thirty percent of your business? Well, that’s OK, because you would have a thirty percent higher margin for seventy percent of your business. You have fewer fools reading your books and you get paid more by those who do. What’s wrong with that?

____________________________

Laura Bennett:

Are you really as relaxed about the future of the industry as you sound?

Andrew Wylie:

I am as calm as I’ve ever been in my life. I was concerned for a while. I think everything’s going to work out.

Laura Bennett:

What would you like to see happen?

Andrew Wylie:

The biggest single problem since 1980 has been that the publishing industry has been led by the nose by the retail sector. The industry analyzes its strategies as though it were Procter and Gamble. It’s Hermès. It’s selling to a bunch of effete, educated snobs who read. Not very many people read. Most of them drag their knuckles around and quarrel and make money. We’re selling books. It’s a tiny little business. It doesn’t have to be Walmartized.•

Tags: Andrew Wylie, Jeff Bezos, Laura Bennett

Philip K. Dick wasn’t widely thought of as an important novelist during his brief life, even though he was speaking as profoundly about the human condition as any of his contemporaries. And he was saying things about consciousness that most of us hadn’t even begun considering. What great things in the culture are we missing right now? Who is being undervalued?

A 1977 interview in France with the author.

Tags: Philip K. Dick

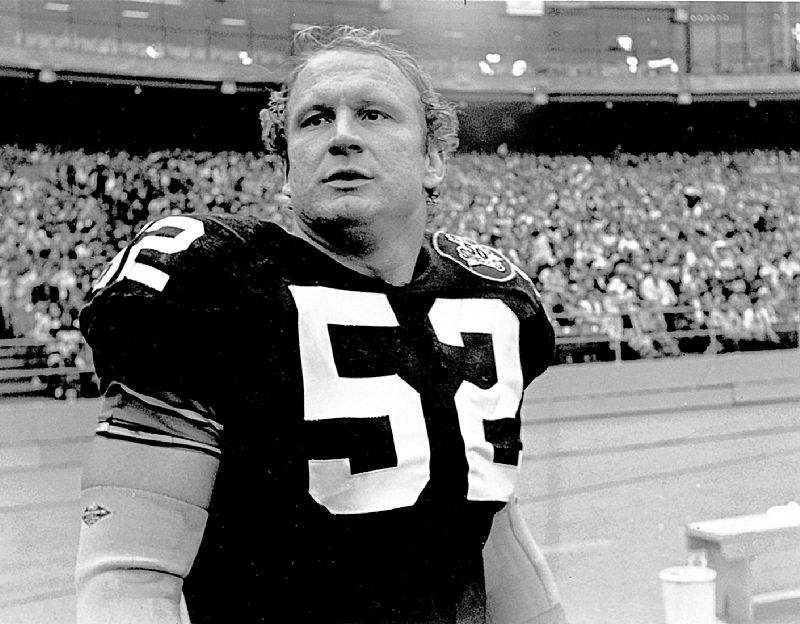

I know it makes me a killjoy, but I feel like any adult who plays in a fantasy football league has failed on some level, has never fully matured. Whenever I hear someone excitedly discussing “their team,” I feel sad. What makes it so bad, of course, is that the players suffer devastating brain damage (and other serious injuries) as part of this entertainment. And the “fantasy” aspect of the game, where teams are imaginary and players merely statistics, has moved us a further distance from this horrifying reality. The NFL has marketed the car-crash violence on Monday Night Football, in video games, and in every way imaginable, only feigning concern for its on-field personnel occasionally for PR purposes, attacking the credibility of those who’ve spoken the truth, like neuropathologist Dr. Bennet Omalu.

Make sure to watch the Frontline episode, “League of Denial: The NFL’s Concussion Crisis,” which takes its impetus from the new book by Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru about the NFL’s terrible record in regard to brain injuries. That it focuses in part on the Pittsburgh Steelers team of the 1970s makes it that much more poignant. It was those Steel Curtain teams partly responsible for pioneering steroid abuse in the NFL.

Tags: Mark Fainaru-Wada, Steve Fainaru

Just as good as Russ Roberts’ EconTalk episode with David Epstein is his recent show with economist Tyler Cowen, whose new book, Average Is Over, looks at life in a more-autonomous future. The guest sees the coming years being increasingly meritocratic, though with merit having shifted from those who are great to those who great at interfacing with machines. On that point is an exchange about freestyle chess, in which a human and computer team up to challenge another computer. Cowen points out that the best human players usually don’t fare too well in these competitions, and are often outdone by lesser players who are superior at knowing when to trust their non-human partner. Cowen guesses at future population distribution in the U.S. and how cities will change, and explains why he thinks income inequality is rising at the same time that crime rates are falling. He’s optimistic about life in 50-70 years, but believes the next few decades will be a painful mix of positives and negatives.

I doubt we’ll ever really be a meritocracy. Even if we were, the idea that a small number of us, 15% or so, will flourish and have tremendous advantages and the rest will be second-class citizens with very nice toys and tools, just makes me sad. Even if it means that we’re wealthier in the aggregate, I still feel depressed about it. Beautiful cities where no poor people can afford to live doesn’t sound Utopian to me. Listen here.

Tags: Russ Roberts, Tyler Cowen

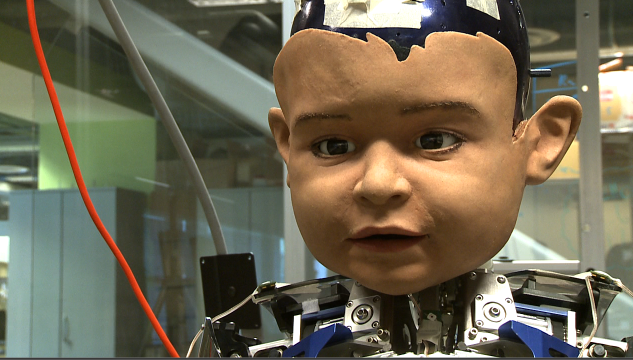

Craig Venter who says outlandish things and makes them seem possible–like here and here–thinks we’ll soon be able to print alien life forms. From the Telegraph:

“Dr Craig Venter, who helped map the human genome, created the world’s first synthetic lifeform, using chemicals and inserting DNA into the cell of a bacteria.

He believes scientists will soon be to do the same, designing basic organisms to include features useful in farming or medicine, as well as sending robots into space to read the sequence of alien life forms and replicate them back on Earth.

Writing in his latest book, Life at the Speed of Light: From the Double Helix to the Dawn of Digital Life, he says: “In years to come it will be increasingly possible to create a wide variety of [synthetic] cells from computer-designed software.'”

Tags: Craig Venter

Have you smelled any good books lately?

The worst argument against ebooks is the sensory one, that dead trees are more pleasing. That you miss how the paper and binding smell. You shouldn’t have been smelling your books anyhow. That’s disgusting. But there are some good points to be made against the digitization of books, in terms of privacy, memory and economics. For some thoughts in the latter category, here’s the opening of Art Brodsky’s new Wired article:

“This is not one of those rants about missing the texture, touch, colors, whatever of paper contrasted with the sterility of reading on a tablet. No, the real abomination of ebooks is often overlooked: Some are so ingrained in the product itself that they are hiding in plain sight, while others are well concealed beneath layers of commerce and government.

The real problem with ebooks is that they’re more ‘e’ than book, so an entirely different set of rules govern what someone — from an individual to a library — can and can’t do with them compared to physical books, especially when it comes to pricing.

The collusion of large ebook distributors in pricing has been a public issue for a while, but we need to talk more about how they are priced differently to consumers and to libraries. That’s how ebooks contribute to the ever-growing divide between the literary haves and have-nots.”

Tags: Art Brodsky

In Felix Salmon’s critique of Dave Eggers’ new novel, he writes glowingly of “It Knows,” Daniel Soar’s 2011 London Review of Books piece about three volumes regarding Google and the place of the Plex in our world. (Or is it our place in the Plex’s world?) A passage about the late GOOG-411 service:

“Levy tells the story of a new recruit with a long managerial background who asked Google’s senior vice-president of engineering, Alan Eustace, what systems Google had in place to improve its products. ‘He expected to hear about quality assurance teams and focus groups’ – the sort of set-up he was used to. ‘Instead Eustace explained that Google’s brain was like a baby’s, an omnivorous sponge that was always getting smarter from the information it soaked up.’ Like a baby, Google uses what it hears to learn about the workings of human language. The large number of people who search for ‘pictures of dogs’ and also ‘pictures of puppies’ tells Google that ‘puppy’ and ‘dog’ mean similar things, yet it also knows that people searching for ‘hot dogs’ get cross if they’re given instructions for ‘boiling puppies’. If Google misunderstands you, and delivers the wrong results, the fact that you’ll go back and rephrase your query, explaining what you mean, will help it get it right next time. Every search for information is itself a piece of information Google can learn from.

By 2007, Google knew enough about the structure of queries to be able to release a US-only directory inquiry service called GOOG-411. You dialled 1-800-4664-411 and spoke your question to the robot operator, which parsed it and spoke you back the top eight results, while offering to connect your call. It was free, nifty and widely used, especially because – unprecedentedly for a company that had never spent much on marketing – Google chose to promote it on billboards across California and New York State. People thought it was weird that Google was paying to advertise a product it couldn’t possibly make money from, but by then Google had become known for doing weird and pleasing things. In 2004, it launched Gmail with what was for the time an insanely large quota of free storage – 1GB, five hundred times more than its competitors. But in that case it was making money from the ads that appeared alongside your emails. What was it getting with GOOG-411? It soon became clear that what it was getting were demands for pizza spoken in every accent in the continental United States, along with questions about plumbers in Detroit and countless variations on the pronunciations of ‘Schenectady’, ‘Okefenokee’ and ‘Boca Raton’. GOOG-411, a Google researcher later wrote, was a phoneme-gathering operation, a way of improving voice recognition technology through massive data collection.

Three years later, the service was dropped, but by then Google had launched its Android operating system and had released into the wild an improved search-by-voice service that didn’t require a phone call. You tapped the little microphone icon on your phone’s screen – it was later extended to Blackberries and iPhones – and your speech was transmitted via the mobile internet to Google servers, where it was interpreted using the advanced techniques the GOOG-411 exercise had enabled. The baby had learned to talk. Now that Android phones are being activated at a rate of more than half a million a day,4 Google suddenly has a vast and growing repository of spoken words, in every language on earth, and a much more powerful learning machine.”

Tags: Daniel Soar, Dave Eggers, Felix Salmon