Long before we used electricity to create friends (and make monsters) on Facebook, Mary Shelley jolted to life a new pal in Victor Frankenstein’s laboratory. Was her creature inspired by the terror of childbirth, or was he delivered due to a radically odd weather event? Perhaps both. From Hannah Gersen at The Millions:

“In winter of 1814, British sailors recorded seeing ‘clouds of ashes’ at the peak of Mount Tambora, a volcanic mountain in the East Indies. A few months later, in the spring of 1815, Tambora exploded with huge, jet-like flames, a column of fire known as a ‘Plinian’ eruption, after Pliny the Younger, who witnessed the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. But Tambora burned hotter than Vesuvius, and it was so powerful that it ejected rock, ash, and other materials into the stratosphere, where they remained suspended, wreaking havoc on global weather patterns for the next three years. 1816 was known as ‘The Year Without Summer’—a relatively mild title for a year that brought famine, disease, and poverty. In the United States, there was snow in June, destroying crops and bringing the country’s first economic depression. In Ireland and China, unremitting rains flooded fields; while in India, monsoon season never arrived. Bacteria flourished in these stagnant, impoverished conditions, and outbreaks of typhus and cholera can be traced back to that dreary, volcanic winter.

I learned these and many other historical details from Gillen D’arcy Wood’s Tambora: The Eruption That Changed The World. Tambora is a new book, but one I discovered haphazardly, through that great portal of haphazardness: Wikipedia. I was fact-checking an overwrought simile (re: procrastinating) and landed on the Wikipedia entry for Frankenstein, where I learned that the great fictional monster was the indirect result of “The Year Without Summer.” I’d never heard of “The Year Without Summer” and in its addictive way, Wikipedia provided a link to an article on the subject, which in turn provided a link to the 1815 Eruption of Mount Tambora, which in turn provided a link to the Pacific Ring of Fire, which in turn led to an article about plate tectonics, which in turn led to a page about super-Earths, which in turn led me to wonder about the origin of the universe and what is the meaning of life on Earth, which I believe is that state of existential confusion to which all Wikipedia rabbit holes eventually lead. I am grateful that on this particular foray, it only took six steps—and also, of course, that it led me to read Tambora, which gave me a glimpse into a startlingly dramatic period in history.

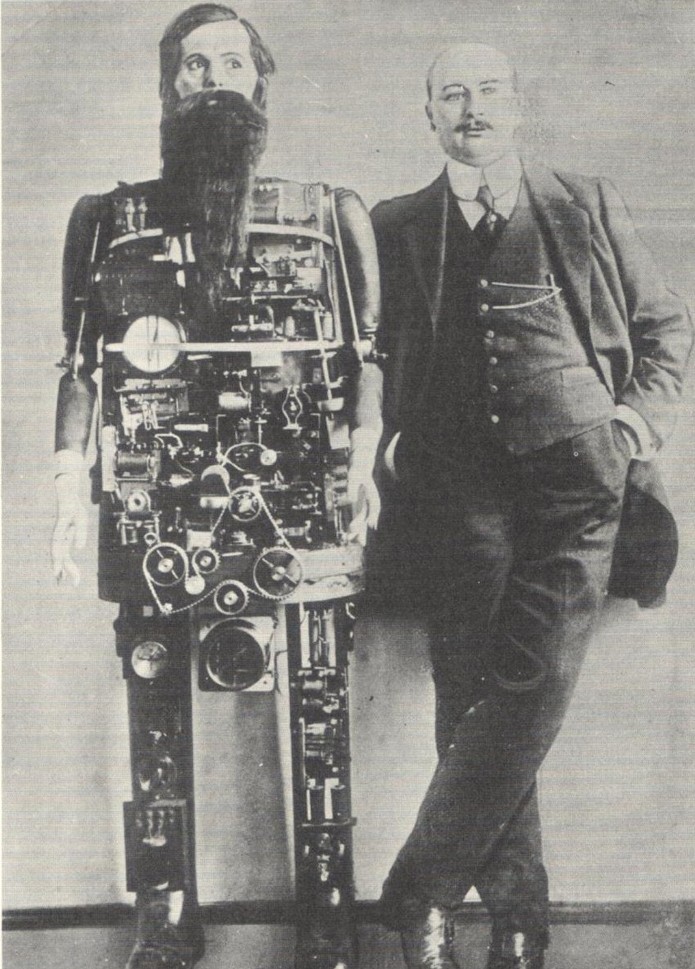

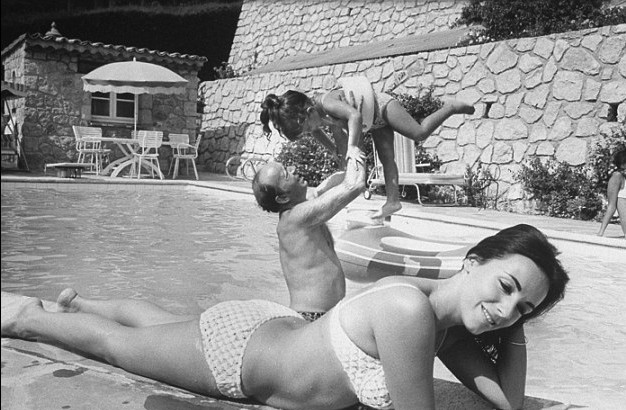

To get back to ‘The Year Without Summer’ (which at this point in July sounds like a marvelous situation) and the creation of Frankenstein, you must transport yourself to a storm-lashed villa on Switzerland’s Lake Geneva. There, sitting in front of a roaring fire, is Percy Shelley, Mary soon-to-be-Shelley Godwin, Mary’s stepsister, Claire Clairmont, Lord Byron, and also, Lord Byron’s doctor (whose presence is somewhat irrelevant, but who I will include, anyway, in the spirit of Wikipedia). This privileged, literary bunch has been driven indoors by unseasonably cold weather, driving rain, and spectacular thunderstorms—all due to Mount Tambora, although of course they don’t know it. Bored and perhaps tired of reciting poetry, they decide to have a contest for who can tell the best ghost story. Mary’s late entry is a tale about a student, Victor Frankenstein, who discovers how to bring life to inanimate material. Frankenstein uses this power to create an eight-foot tall “creature” who is never given a name, but who eventually kills Frankenstein’s wife and escapes to the North Pole. It’s not a ghost story but a monster story, one inspired by Shelley’s extensive readings into science and myth.

Wood argues that Frankenstein was also inspired by the stormy, Tambora-induced weather, and that ‘the pyrotechnical lightning displays’ raging outside Shelley’s villa windows were written into the novel.”