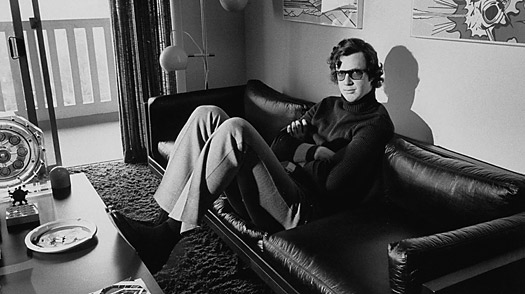

Michael Crichton was one of the more unusual entertainers of his time, a pulp-ish storyteller with an elite education who had no taste–or talent?–for the highbrow. He made a lot of people happy, though scientists and anthropologists were not often among them. The following excerpt, from a 1981 People portrait of him by Andrea Chambers, reveals Crichton (unsurprisingly) as an early adopter of personal computing.

_____________________________

At 38, he has already been educated as an M.D. at Harvard (but never practiced), written 15 books (among them bestsellers like The Andromeda Strain and The Terminal Man), and directed three moneymaking movies (Westworld, Coma and The Great Train Robbery). He is a devoted paladin of modern painting whose collection, which includes works by Frank Stella and Robert Rauschenberg, recently toured California museums. In 1977, because the subject intrigued him, Crichton wrote the catalogue for a Jasper Johns retrospective at Manhattan’s Whitney Museum. “Art interviewers tend to be more formal and discuss esthetics—’Why did you put the red here and the blue there?’ ” says Johns. “But Michael was trying to relate me to my work. He is a novelist and he brings that different perspective.”

Crichton’s latest literary enterprise is Congo (Alfred A. Knopf), a technology-packed adventure tale about a computer-led diamond hunt in the wilds of Africa. Accompanied by a friendly gorilla named Amy, Crichton’s characters confront everything from an erupting volcano to ferocious apes bred to destroy anyone who approaches the diamonds. The novel has bobbed onto best-seller lists, despite critical sneers that it is “entertaining trash.” (A New York Times reviewer called it “literarily vapid and scientifically more anthropomorphic than Dumbo.”)

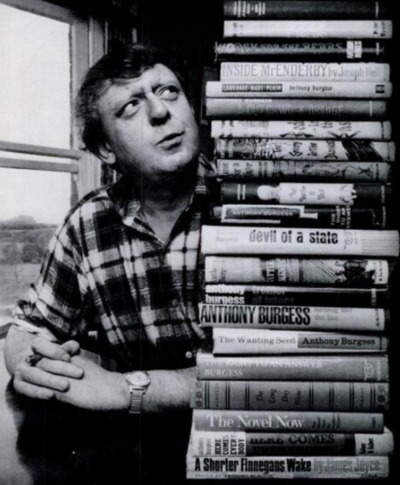

Crichton cheerfully admits that Congo owes more than its exotic locale to Sir Henry Rider Haggard’s classic King Solomon’s Mines. “All the books I’ve written play with preexisting literary forms,” Crichton says. A model for The Andromeda Strain was H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. The Terminal Man was based on Frankenstein’s monster. Crichton’s 1976 novel Eaters of the Dead was inspired by Beowulf. “The challenge is in revitalizing the old forms,” he explains.

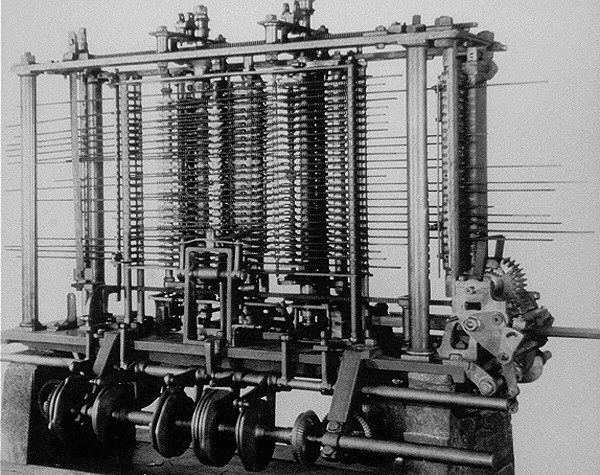

Crichton taps out his books on an Olivetti word processor (price: $13,500) and bombards readers with high-density scientific data and jargon, only some of which is real. “I did check on the rapids in the Congo,” he says. “They exist, but not where I put them.” His impressive description of a cannibal tribe is similarly fabricated. “It amused me to make a complete ethnography of a nonexistent tribe,” he notes. “I like to make up something to seem real.”•