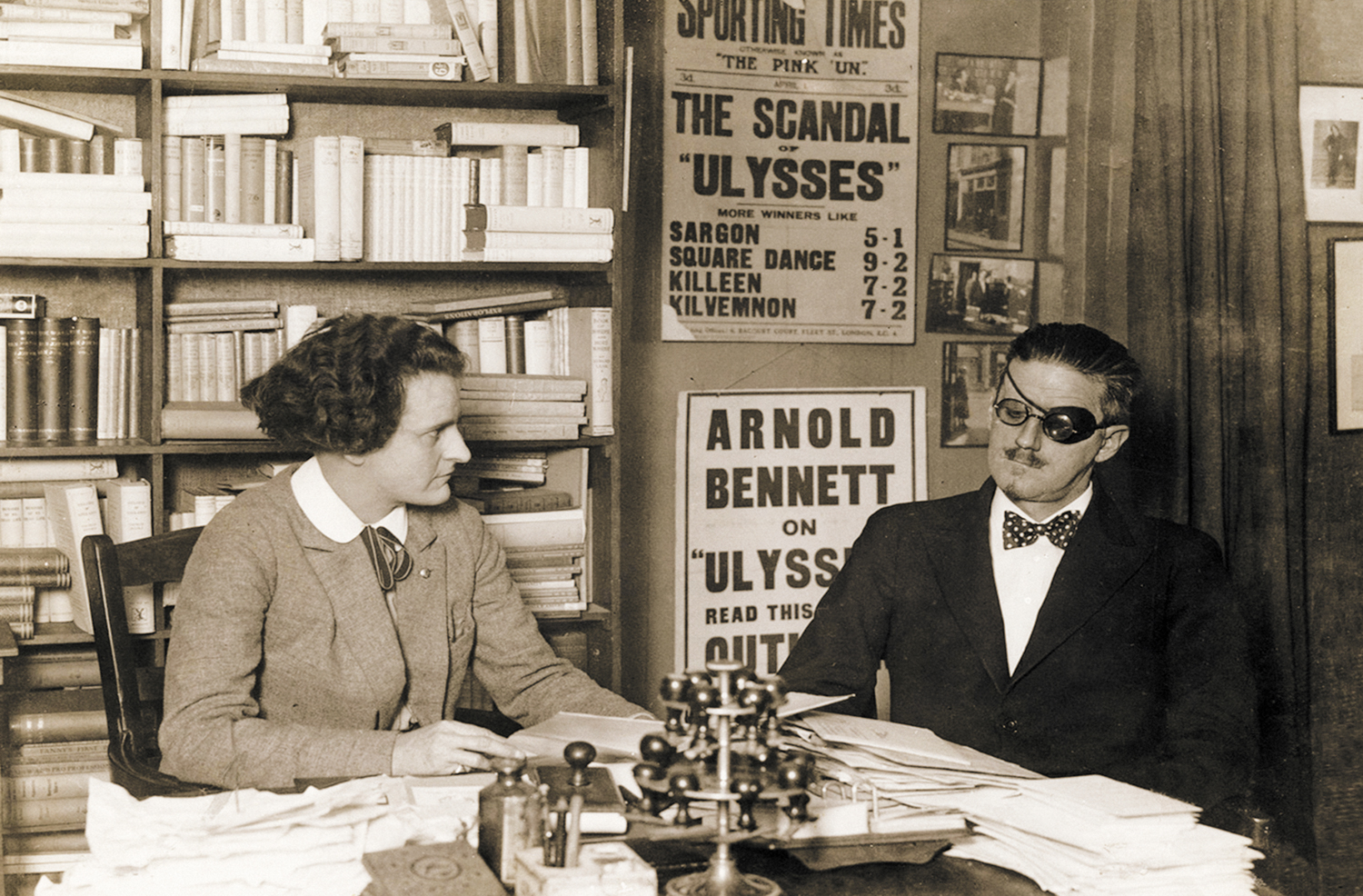

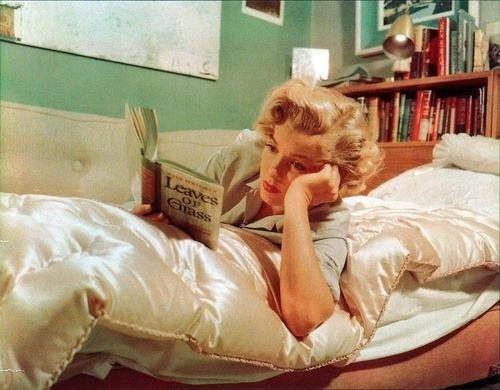

I can’t guarantee there will always be Broadway, but I’m sure there will always be theater. I feel the same way about books, even if brick-and-mortar stores are (sadly) in a steep decline. There will permanently be a hunger for written stories.

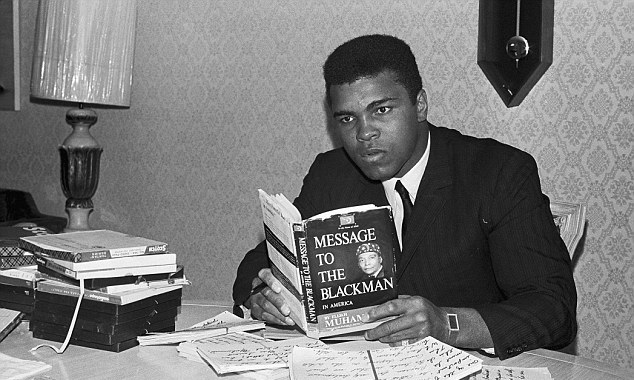

Of course, it takes some training to take advantage of the endless supply of volumes now available to us, and James Patterson is concerned that reading is an endangered species. He’s right to question what an Amazon monopoly on book pricing might mean, though I think the money he’s allocating to TV ads encouraging reading might be better spent on simply buying comic books for low-income families with young children. Having grown up in very modest circumstances and having learned to read on Mad magazine, I can vouch for such a plan. Based on his interview with Erin Keane of Salon, Patterson is certainly aware of the power of pleasure reading early in life. An excerpt:

“Question:

What’s the goal here? More independent bookstores, more book sales?

James Patterson:

I think the goal is just more people reading. And to do that, a lot of things have to happen. Actually, to me, the group that can do the most good here is Amazon. Amazon could actually dedicate itself to saving books and literature in this country. It really could. And that would be the easiest fix, directionally.

I think they probably think they’re doing that, but they’re not, at least not yet. Yes, they want to lower prices, and you know, theoretically that’s fine, but I don’t know how we’d do that on a practical level and keep stores… You know, in terms of evolving the system as opposed to fracturing the system, [Amazon is] in a position to do something. The government is in a position to do something. Ironically, you know, we have a very liberal president, and he doesn’t seem terribly interested in the subject, unfortunately. I know he’s got a lot on his plate already, but you know. I mean, look, all over Europe you have governments who protect the publishers and protect books.

Question:

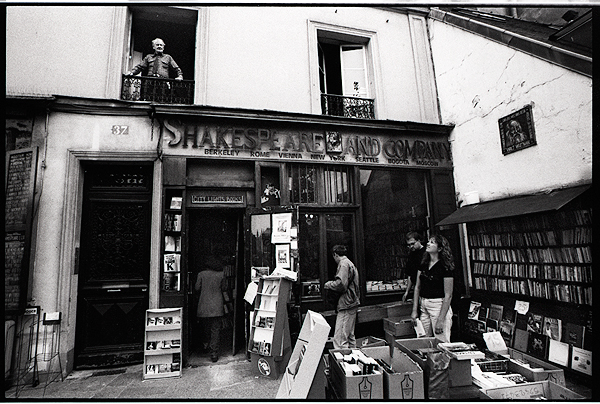

Yeah, there was that New York Times Bookends piece recently about how France treats books as an ‘essential good,’ like food and utilities. They’re taxed at lower rates, price discounts are pretty severely controlled. Is that a model that you think would be useful?

James Patterson:

No, I don’t think it’s a model, but I think it’s something to pay attention to. I think the government could be more involved. I mean, obviously the government has stepped in when banks were in trouble and the automobile business was in trouble. I think it’s something that local, state and federal government could be doing more.

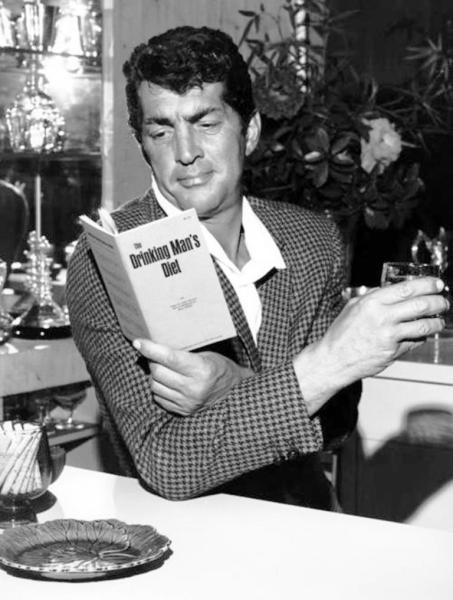

This is once again symbolic, the kind of leadership pledge, you know. We’re gonna ask people to write to the President, write to their Congress and their representatives. And have the President take a pledge that once a month, he’ll appear in public carrying a book, he’ll visit a library store, or you know, the local representative. And then to have some of these [politicans] going on record in government sessions that they’re concerned about the state of reading in our country. And they should be.

Because, look, with our kids, and that’s a big deal with me, kids are not reading as broadly as they should and as they used to. We’re getting more and more of this kind of tunnel-vision, get on your little mission to become a doctor, lawyer, mathematician, engineer, etc., and [kids] really don’t read. My son’s at a very good prep school, and they don’t read as much as I’d like them to do, in terms of breadth of reading. You know, they don’t know who a lot of the famous authors [are]. Not that they should matter who they are, but … my own thing about kids at the top [is] that in the course of high school they’re exposed to a couple hundred really good, interesting authors, you know, ranging from Toni Morison to Cormac McCarthy to Truman Capote to Saul Bellow, etc., etc., and just be familiar with different voices and ways of looking at the world. I think that’s important in terms of really good readers.

More important, maybe, is at-risk kids, because, and this is a big deal with me, I do a lot, as much as any individual can do, but at-risk kids, if they’re not… if they don’t become competent readers—I’m not talking about readers for life, I’m talking about competent readers—how are they going to get through high school? If you’re not a competent reader. And that’s an epidemic around this country, kids who cannot read at a competent level. How you gonna do history, how you gonna do science? You just can’t. I mean, you sit there and you struggle and it takes 15 minutes to read the first page. That doesn’t work. In a lot of cases, it’s correctible.

Question:

There’s research that says that kids who grow up in a household where there are books in the house are more likely to become constant readers than those who don’t.

James Patterson:

That’s a piece of it. That’s a piece of it. What happens in the schools is a piece of it. I just gave a talk, and I was asked to talk on this subject in front of all of the middle school principals in New York City, public schools, and they asked me to talk about the principals encouraging students to read for fun, to read extra stuff, to read outside of the Common Core, to read things, because the more they read the better they get at it. It’s really simple. I’ll go into schools and I’ll go, ‘Who plays soccer?’ ‘Yeah! Yeah, yeah, yeah!’ ‘You better now or three years ago?’ ‘We’re better now! Yeah!’ ‘How come?’ ‘Cause we play a lot! Yeah!’ ‘Okay, same thing, dudes.’ If you read, and you can read fun stuff, you can read comic books, you can read a lot of different… there’s a lot of ways to get that exercise, get that reading muscle worked on. If you do that, you will become good readers, and school will be easier.“