Between this corner and the Bowery, Bleecker Street is like a river running into swamp, block after block with no definable character. It is neither market nor tenement nor warehouse district, but a nondescript mixture of these, with a few grimy luncheonettes and some slum lofts thrown in: a vacuum. A walk down this end of Bleecker is an exercise in induced despair, emotional slumming. The cityscape here is so desolate that it becomes surreal. You feel that behind the brick building fronts there is nothing but emptiness, fixtures connecting nothing to nothing, stairs leading up to doors that open onto a void. At Crosby you come to the Bayard Building, the only work of Louis Sullivan that is left in New York. The façade, particularly in this setting, is magnificent. Beyond it, a two-minute walk will put you on the Bowery, where nothing ever changes.

By the press, the politicians, the police and the populace, Bleecker Street has been called practically everything: a “hotbed of incipient violence,” a slum, a honkytonk, a refuge for homosexuals and/or miscegenists, a hangout for beatniks and commies and dope fiends, a shameless tourist trap. But whatever it may or may not be, whatever strange flavors outsiders bring to it, Bleecker is primarily, prevailingly Italian.

There is an old blind man who sits in the afternoons near the corner at Sixth Avenue. He told me once that he has never left Naples. He sits close enough to the Hudson to smell the harbor, and all around him are the aromas of new produce, olive oil, fennel, roasting coffee and freshly killed meat. At least as much Italian is being spoken as English.

Bleecker Street days are not much like Bleecker Street nights. Afternoons are taken up by the business of the neighborhood: the schooling and recreation of children, the purchase of groceries, the delivery of commodities to fifty shops and stalls up and down the street. Whatever social life the older residents have is conducted on these sidewalks during daylight hours, when the sidewalks are still theirs.

On these afternoons there is a moon-faced woman in black polka-dotted housedress who leans on a crate of fresh plums, gesturing to customers over baskets of grapes. Her prices are marked, but she will tolerate a limited amount of bargaining. Some of this bargaining has gone on between her and the same customers for over twenty years. Up the street some old men in shirtsleeves stand in front of Ruggiero’s Fish Market, lunching on oysters from a card table set up on the sidewalk. They prepare each one separately, adding hot sauce and lemon. A Negro workman comes up to the table, and the old men throw down some coins and leave. At the corner, one of them mutters, “Mulignam!” a dialect expression for eggplant, which is also their pejorative for Negroes. Then they cross the street to Father Demo Square. Of course the Negro knows what has happened.

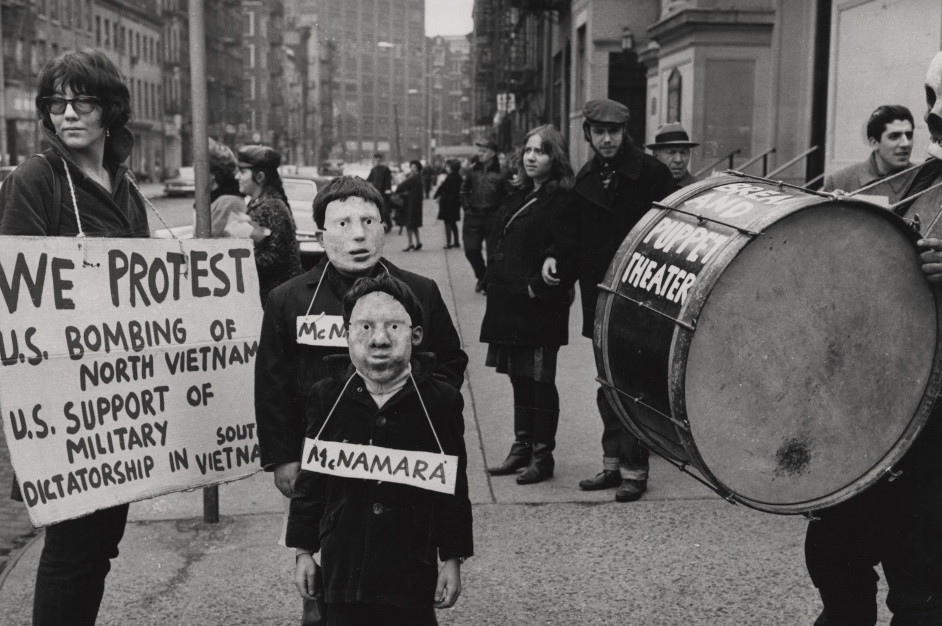

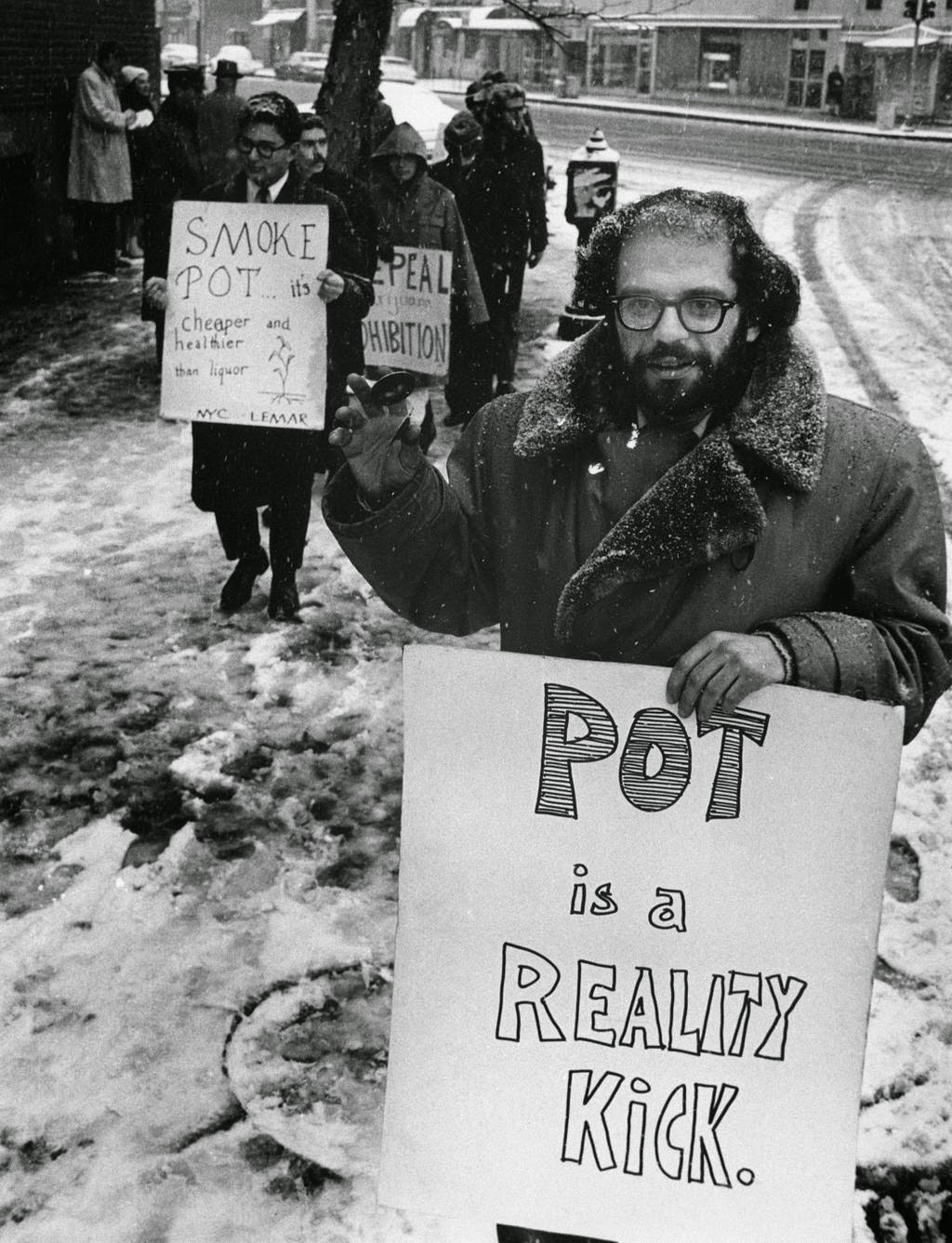

This parade route for visiting liberals. anarchists, socialists, apolitical grousers, peace marchers and civil-rights workers is also a neighborhood of Ghibelline rigidity, prejudice, reaction. Not long ago the Carmine DeSapio sound trucks cruised along here begging votes in blaring Calabrese dialect. Now you can see the remains of a Goldwater poster peeling to reveal the spattered likeness of De Sapio oil brick walls at street corners, and the traditional Democratic block is finished. The mounting tourist traffic is an outrage to the residents, particularly among first-generation immigrants. For them, the thought of miscegenation is unbearable, and you can feel the hatred this generates up and down the length of the street. Some of the locals have turned this influx to their advantage, opening bars, restaurants and galleries, but most sit locked in severe parochial resentment. If the Evil Eye really worked, the sidewalks would be strewn with paralytics, heaped with the blind and the dead.

_______________________________

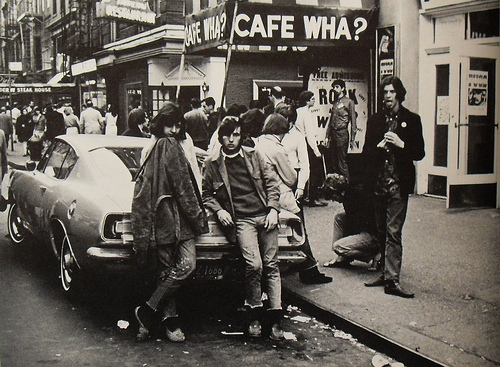

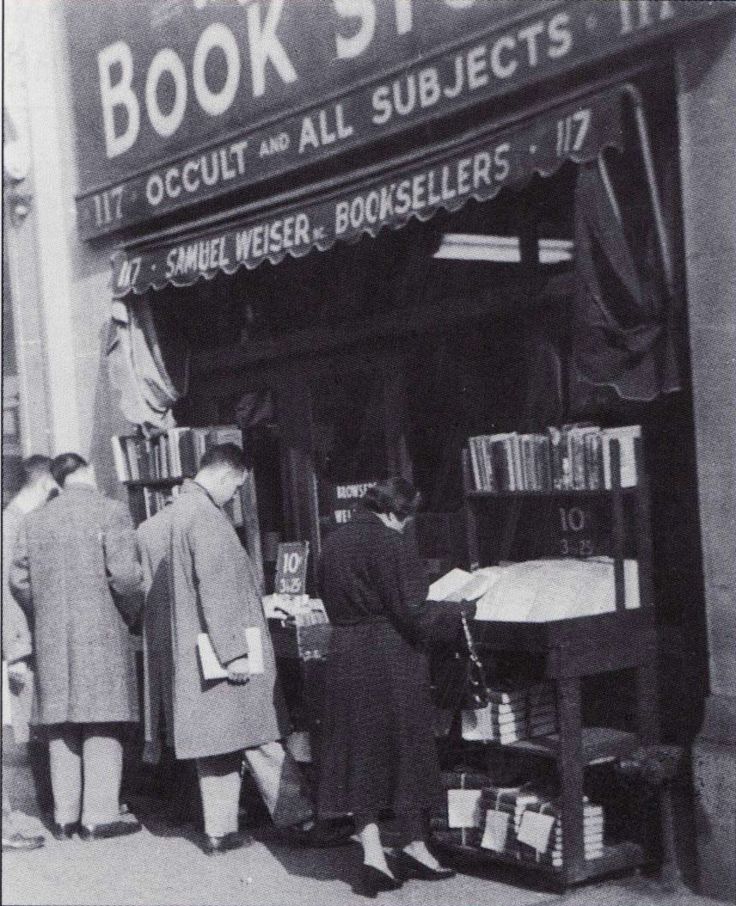

They call MacDougal “the Mess,” and not without reason. In summer, at the corner where it crosses Bleecker, the sidewalks are clogged every night of the week. During the rest of the year the crowds come only on weekends, but they come in such numbers that they make up for the Monday-through-Thursday calm. No one knows exactly what brings them or who they are or even who they think they are, but there are a lot of them. The word is out that this is Where It’s At. As usual, the word lies, but none of the thousands, the tens of thousands, who come here night after night will ever admit it.

Most of them are young, under twenty, of a type that used to be written of as “beatnik.” But that word hasn’t meant anything for years, and it certainly doesn’t apply to this crowd. These are cultists whose beliefs are murky, a whole generation sprung half-baked from a badly digested notion of Bohemia, malnurtured on mass-media accounts of groovy goings-on from Liverpool to Berkeley. What they appear to want, more than anything else, is to enchant, but there never seem to be any takers. They are the sons and daughters of Tarrytown orthodontists, Rochester retailers, Long Island manufacturers, Jersey City construction workers, all come to conduct one of the most elaborate flirtations in history. And they are not the only ones; their parents come, too, impeccably polished. expensively dressed, and they come for almost the same reason. Everyone wants his slice of hip cake.

Once, it was the bourgeoisie’s had joke to say they couldn’t tell the boys from the girls. but this is no longer a joke. Young men, apparently not homosexual, wear their hair shoulder-length: if it were cleaner you might say it flowed. It is a part of the fashion, and the MacDougal-Bleecker crowd pays careful attention to fashion. The real hippies have been forced into coats and ties, now that their old turf has been overrun by creeps.

It was the fashion, for several weeks last spring, for girls to walk along Bleecker carrying a single flower. If they could get nothing better, they would carry a plastic flower, but there were dozens of these girls with their flowers. That ended. They turned up wearing those Liverpool sailors’ hats. And little white ankle boots. Then bellbottomed denim slacks with broad-striped jerseys worn loose around the waist. On dress occasions they wore discotheque dresses and patterned stockings that made the skin on their legs look diseased. Then the boys began wearing watch caps—hadn’t the Beatles introduced them?—and a few even started wearing the slacks. The esoterics, gurus and prep-school liberals took to wearing rimless glasses, often with hexagonal lenses, and with the glasses came effete Danish pipes, and floppy felt hats like the ones W. B. Yeats used to wear—all kinds of Yellow Bookish paraphernalia. Fashion. And they come down here to parade all this, each one sure that the Village has never seen anything like it.

After dark the sidewalks become so crowded that you have to take odd little two-inch steps or else walk around the cars, police and motorcycles in the street. If you have had the practice you can discern the slightest trace of marijuana in the air, although they say that it is only Sano cigarette smoke. There is usually music, either from a passing folkie or from a transistor radio.

There is a folksong that goes:

When I die please bury me deep,

Down at the end of Bleecker Street,

So I can hear old Number Nine,

As she goes rolling by.

I can’t find out what this really means.•