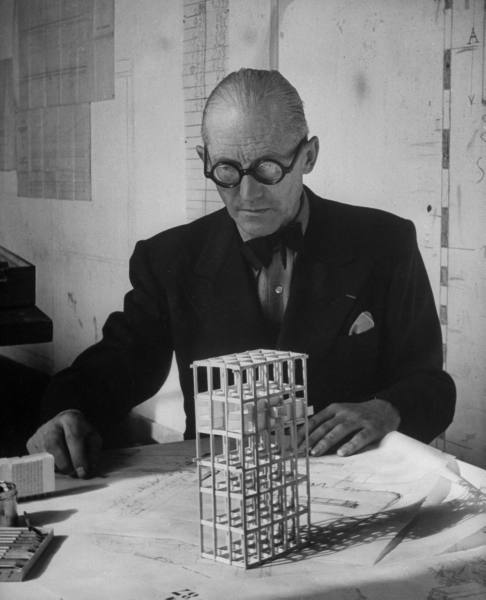

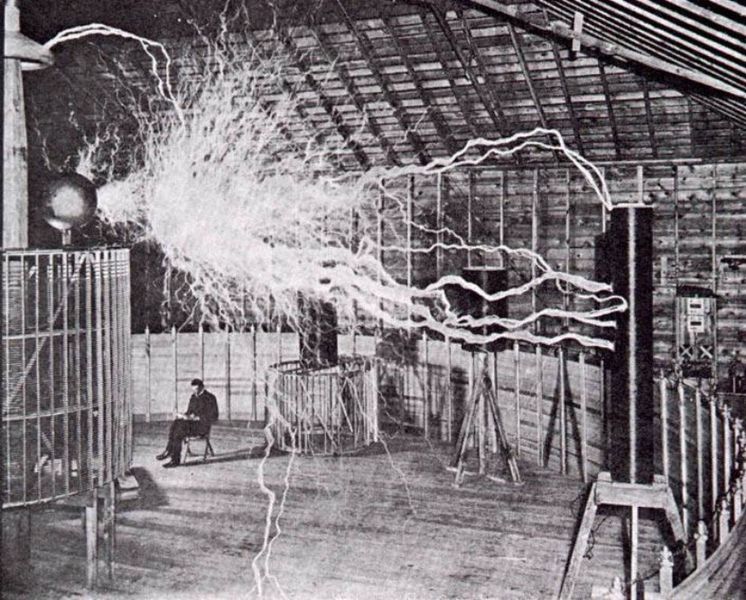

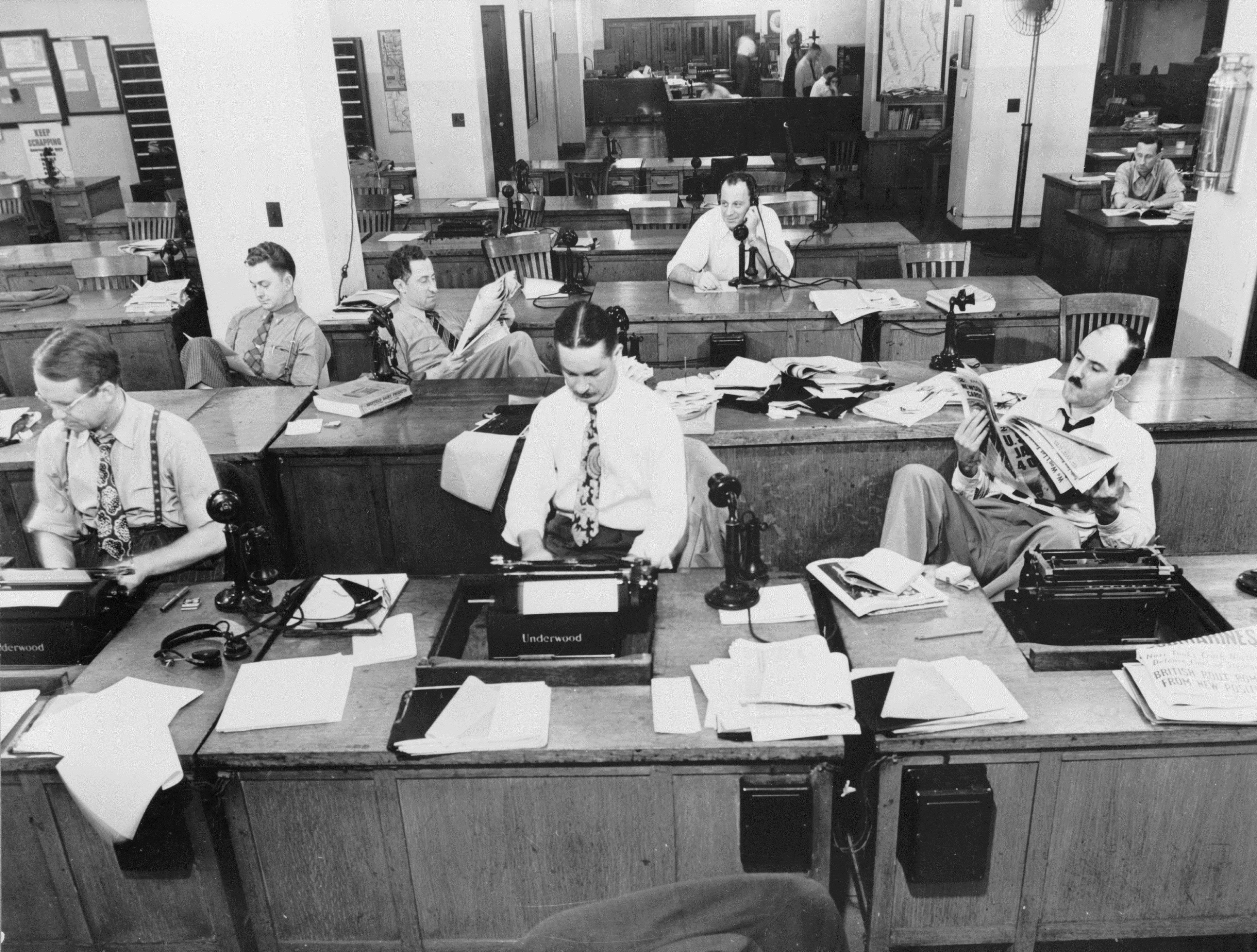

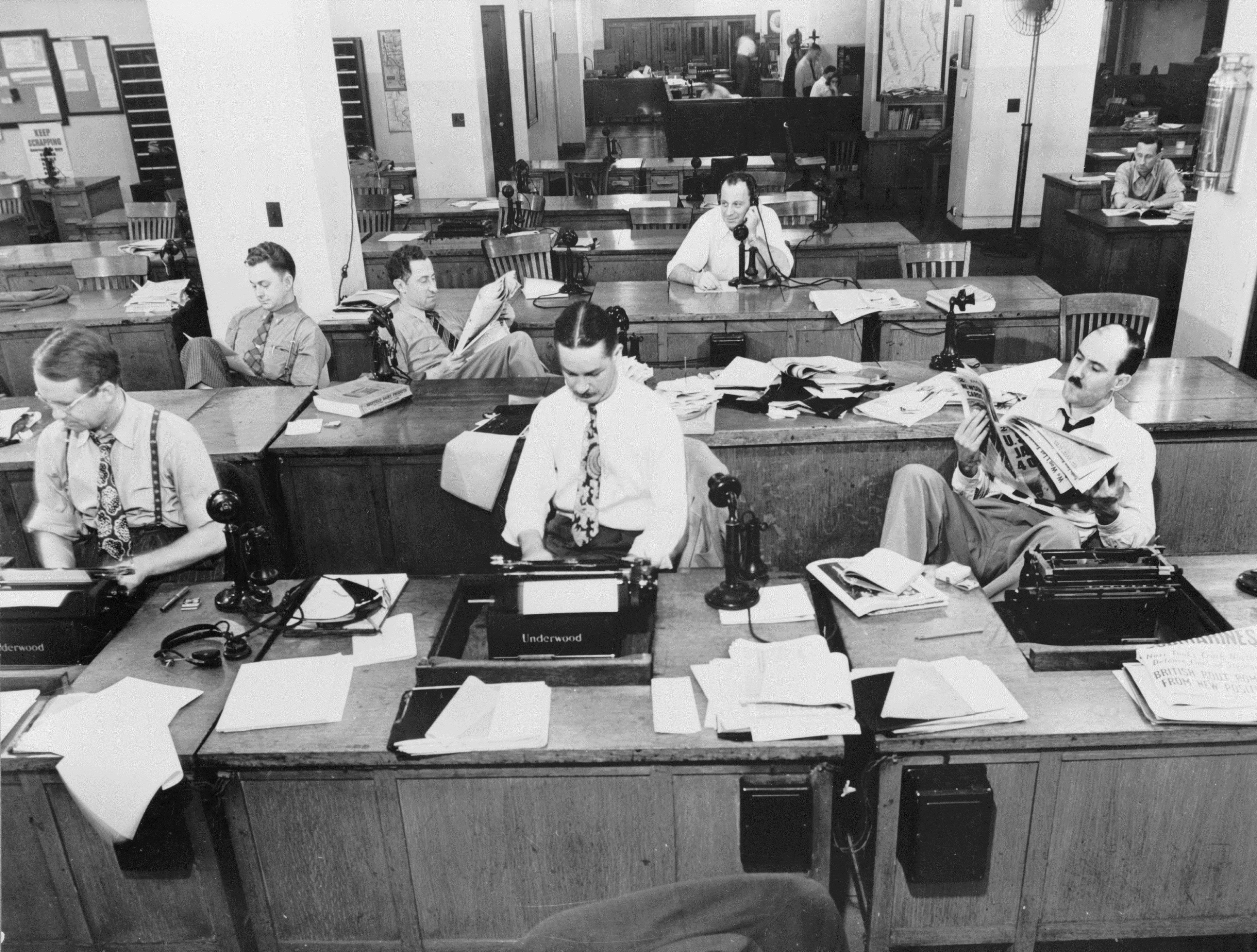

New York Times newsroom, 1942.

There might not always be Broadway, but they’ll always be theater. Certainly, there won’t always be printed newspapers, but there will always be journalism. Divining the formula to support important work that doesn’t produce money is the rub, of course. But I do believe it will happen, even if the transition is painful.

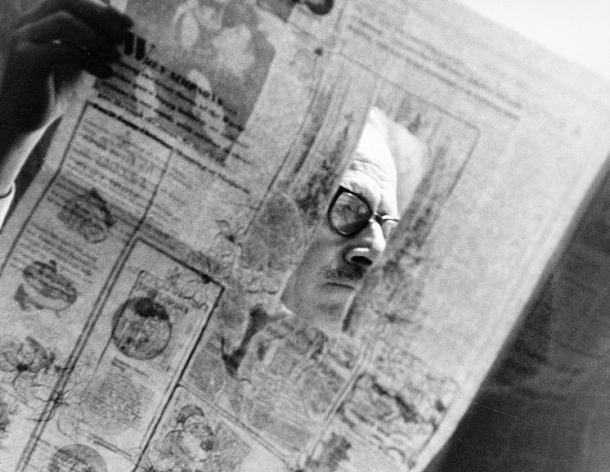

In 1975, in a New Yorker piece, “P-1800” (which is paywalled), John McPhee looked at that moment when the New York Times was first trying to transition from typewriters to computers, to create a work environment that was portable and largely paperless, even before that last term was coined and there became little choice in the matter. It involved not only word processing but being able to send the work via telephone line and save it to disc. The opening:

“Joseph Martin, a computer methodologist at the Times has been pursuing for years what he describes as ‘the ideal philosophy of creating a newspaper.’ According to the ideal philosophy, you start by ‘capturing the keystroke at the origin.’ Keystroke? The reporter, at the typewriter, hits the original keystrokes of a story. Martin aims to absorb them electronically, retain them in a computer, and eliminate all the laborious and manifold retypings that now occur as a piece of writing makes its way, typically, from reporters through bureaus to the home office to the desks of editors and eventually to linotype machines. The ideal philosophy also calls for the elimination of the typing paper that writers write on, which is regarded as an unnecessary and archaic encumbrance. Following suggestions of reporters and editors, and with the help of an electronics firm in Westchester, Martin has coaxed into being a device that can actually do this. The Times is just up the street from us. We went over there the other day to have a look.

In the third-floor newsroom, we found routine cacophony: a large open space as aswarm with bodies as the floor of a stock exchange, copy paper in motion everywhere, copy editors looking like physicists with crooked cigarettes and feral eyes, reporters hugging telephones or already down in the trenches–sporadic bursts of typing. The machine that was going to tranquilize this scene was locked away in a quiet cubicle. We were led to it by Joe Martin, a slim and somewhat solemn man with graying crewcut, and by Socrates Butsikares, an editor of decades’ experience on various news and feature desks, who now coordinates editorial-staff interests with those of the rest of the company and is thus deeply involved in the electronic innovation. A big man, Butsikares wore a bright-yellow shirt, and there were lemons on his tie. We were joined as well by Israel Shenker, who is an old friend of ours and is one of the Times’ bright-star reporters and most skillful writers. Shenker had not previously seen the machine that was designed to change the world.

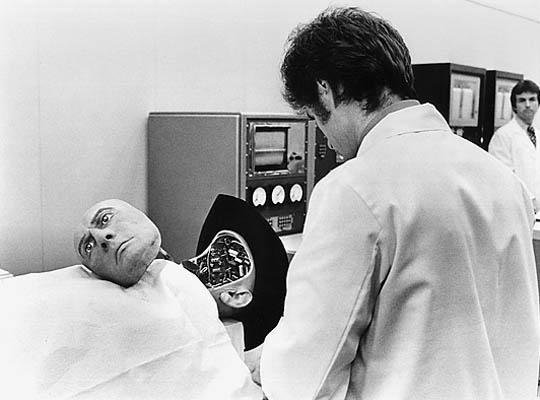

At thirty-two pounds, it rested heavily on a table. Resembling a small blue suitcase, it was eighteen inches by thirteen by seven. It would fit under an airline seat. Its name was Teleram P-1800 Portable Terminal. Butsikares unpacked it. Its principal components were a TV-like cathode-ray tube and a freestanding keyboard that had the conventional ‘qwertyuiop’ arrangement of a typewriter keyboard plus flanking sets of keys that had designations such as ‘SCRL,’ “HOME,’ ‘DEL WORD,’ ‘DEL CHAR,’ ‘CLOSE,’ ‘OPEN,’ and ‘INSRT.’

At thirty-two pounds, it rested heavily on a table. Resembling a small blue suitcase, it was eighteen inches by thirteen by seven. It would fit under an airline seat. Its name was Teleram P-1800 Portable Terminal. Butsikares unpacked it. Its principal components were a TV-like cathode-ray tube and a freestanding keyboard that had the conventional ‘qwertyuiop’ arrangement of a typewriter keyboard plus flanking sets of keys that had designations such as ‘SCRL,’ “HOME,’ ‘DEL WORD,’ ‘DEL CHAR,’ ‘CLOSE,’ ‘OPEN,’ and ‘INSRT.’

Butsikares plugged the keyboard unit into the TV-screen unit, sat down, and began to write. As his fingers fluttered, words instantly surfaced on the screen, up to forty-four characters per line:

WASHINGTON, D.C.–President Ford said today that he would no longer ask the Congress to soak the poor while his fat-cat rich friends take away the wealth of the Republic.

‘Now, suppose you want to get a little color into this,’ Butsikares said, and he began tapping keys–marked with arrows pointing up, pointing down, pointing sideways–around the word ‘HOME.’ A tiny square of light known as the ‘cursor’ began to move up the face of the tube. It was something like the bouncing ball that used to hop from word to word in song lyrics on movie screens. It climbed to the first line, then moved left until Butsikares stopped it in the space between ‘Ford’ and ‘said.’ He tapped the ‘INSRT’ key. He then wrote:

, who was wearing his faborite blue suit and his soup-stained blue tie,

The new words came into the space after ‘Ford,’ and to accommodate them the cursor kept shoving to the right all the other words in the sentence. They went around corners and down the screen. Busikares moved the cursor until it rested upon and illuminated the ‘b’ in ‘faborite.’ He pressed the ‘DEL CHAR’ (delete character) button, and the ‘b’ vanished. He replaced it with a ‘v.’ ‘Now, suppose you want to take a word out,’ he said, and moved the cursor to the word ‘away.’ ‘All the cursor has to do is touch any part of the word,’ he went on. ‘Then you hit the ‘DEL WORD’ key, and it’s gone.’ Away went ‘away,’ and the words to either side moved to within a space of each other. Similarly, the cursor could–if directed to–eat whole lines, whole paragraphs. ‘What you have written is not set in cement,’ Butsikares said. ‘You can change anything easily. If I had my druthers, I’d rather write on this thing than on any typewriter I’ve ever seen.”•