I’ve always believed that smaller offices in which there is a great deal of incidental interaction is a way more productive environment than spacious, comfy quarters. In a segment of “True Innovation,” Jon Gertner’s New York Times Opinion piece about creativity in America, the author explains the guiding principles of Mervin Kelly, one of the leading lights of Bell Labs during its glorious future-building run in the 20th century, who designed architecture that forced employee contact. An excerpt:

“At Bell Labs, the man most responsible for the culture of creativity was Mervin Kelly. Probably Mr. Kelly’s name does not ring a bell. Born in rural Missouri to a working-class family and then educated as a physicist at the University of Chicago, he went on to join the research corps at AT&T. Between 1925 and 1959, Mr. Kelly was employed at Bell Labs, rising from researcher to chairman of the board. In 1950, he traveled around Europe, delivering a presentation that explained to audiences how his laboratory worked.

His fundamental belief was that an ‘institute of creative technology’ like his own needed a ‘critical mass’ of talented people to foster a busy exchange of ideas. But innovation required much more than that. Mr. Kelly was convinced that physical proximity was everything; phone calls alone wouldn’t do. Quite intentionally, Bell Labs housed thinkers and doers under one roof. Purposefully mixed together on the transistor project were physicists, metallurgists and electrical engineers; side by side were specialists in theory, experimentation and manufacturing. Like an able concert hall conductor, he sought a harmony, and sometimes a tension, between scientific disciplines; between researchers and developers; and between soloists and groups.

ONE element of his approach was architectural. He personally helped design a building in Murray Hill, N.J., opened in 1941, where everyone would interact with one another. Some of the hallways in the building were designed to be so long that to look down their length was to see the end disappear at a vanishing point. Traveling the hall’s length without encountering a number of acquaintances, problems, diversions and ideas was almost impossible. A physicist on his way to lunch in the cafeteria was like a magnet rolling past iron filings.”

••••••••••

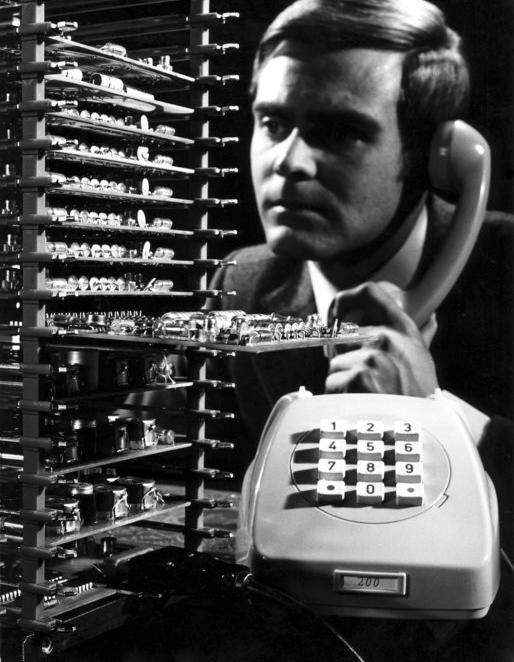

1960s computer animation by Bell Labs visual neuroscientist Béla Julesz:

Tags: Béla Julesz, Jon Gertner, Mervin Kelly