From “Say No More,” Jack Hitt’s 2004 New York Times Magazine piece about language death, a segment about the Kawésqar tongue of Chile:

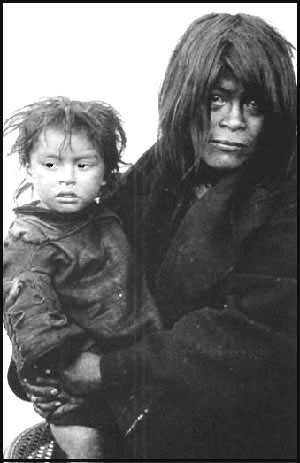

“”The Kawesqar are famous for their adaptation to this cold, rainy world of islands and channels. The first Europeans were stunned. The Kawesqar and the other natives of the region traveled in canoes, naked, oiled with blubber, occasionally wearing an animal skin. The men sat at the front and hunted sea lions with spears. The women paddled. The children stayed in the sanctuary between their parents, maintaining fire in a sand pit built in the middle of the canoe. Keeping fire going in a land of water was the most critical and singular adaptation of the Kawesqar. As a result, fire blazed continuously in canoes and at the occasional landfall. The first European explorers marveled at the sight of so much fire in a wet and cold climate, and the Spanish named the southernmost archipelago the land of fire, Tierra del Fuego.

When Charles Darwin first encountered the Kawesqar and the Yaghans, years before he wrote The Origin of Species, he is said to have realized that man was just another animal cunningly adapting to local environmental conditions. But that contact and the centuries to follow diminished the Kawesqar, in the 20th century, to a few dozen individuals. In the 1930’s, the remaining Kawesqar settled near a remote military installation — Puerto Eden, now inhabited mostly by about 200 Chileans from the mainland who moved here to fish.

The pathology of a dying language shifts to another stage once the language has retreated to the living room. You can almost hear it disappearing. There is Grandma, fluent in the old tongue. Her son might understand her, but he also learned Spanish and grew up in it. The grandchildren all learn Spanish exclusively and giggle at Grandma’s funny chatter.

In two generations, a healthy language — even one with hundreds of thousands of speakers — can collapse entirely, sometimes without anyone noticing. This process is happening everywhere. In North America, the arrival of Columbus and the Europeans who followed him whittled down the roughly 300 native languages to only about 170 in the 20th century. According to Marianne Mithun, a linguist at the University of California at Santa Barbara, the recent evolution of English as a global language has taken an even greater toll. ‘Only one of those 170 languages is not officially endangered today,” Mithun said. ‘Greenlandic Eskimo.'” (Thanks TETW.)

Tags: Jack Hitt