Walter Kirn went a little hyperbolic in his 2007 Atlantic essay about the high cost of multitasking in the Information Age, but it’s still a provocative piece. An excerpt;

“It isn’t working, it never has worked, and though we’re still pushing and driving to make it work and puzzled as to why we haven’t stopped yet, which makes us think we may go on forever, the stoppage or slowdown is coming nonetheless, and when it does, we’ll be startled for a moment, and then we’ll acknowledge that, way down deep inside ourselves (a place that we almost forgot even existed), we always knew it couldn’t work.

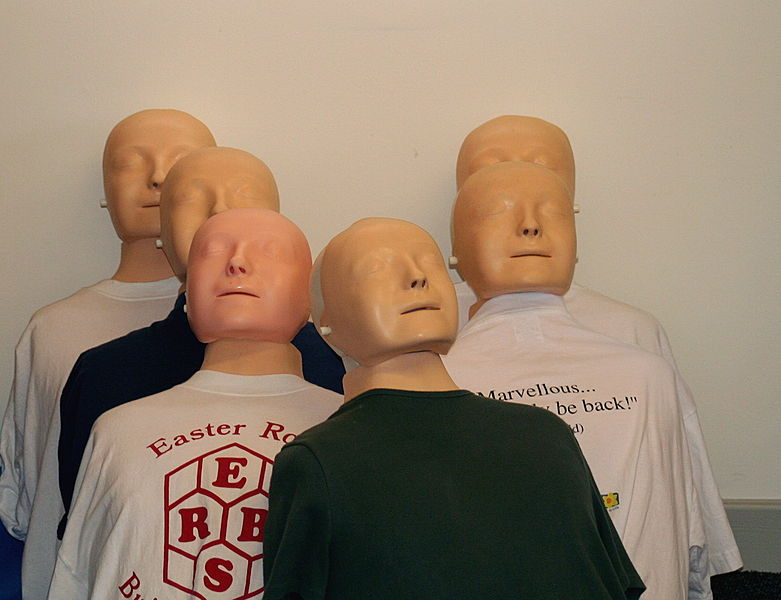

The scientists know this too, and they think they know why. Through a variety of experiments, many using functional magnetic resonance imaging to measure brain activity, they’ve torn the mask off multitasking and revealed its true face, which is blank and pale and drawn.

Multitasking messes with the brain in several ways. At the most basic level, the mental balancing acts that it requires—the constant switching and pivoting—energize regions of the brain that specialize in visual processing and physical coordination and simultaneously appear to shortchange some of the higher areas related to memory and learning. We concentrate on the act of concentration at the expense of whatever it is that we’re supposed to be concentrating on.

What does this mean in practice? Consider a recent experiment at UCLA, where researchers asked a group of 20-somethings to sort index cards in two trials, once in silence and once while simultaneously listening for specific tones in a series of randomly presented sounds. The subjects’ brains coped with the additional task by shifting responsibility from the hippocampus—which stores and recalls information—to the striatum, which takes care of rote, repetitive activities. Thanks to this switch, the subjects managed to sort the cards just as well with the musical distraction—but they had a much harder time remembering what, exactly, they’d been sorting once the experiment was over.

Even worse, certain studies find that multitasking boosts the level of stress-related hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline and wears down our systems through biochemical friction, prematurely aging us. In the short term, the confusion, fatigue, and chaos merely hamper our ability to focus and analyze, but in the long term, they may cause it to atrophy.”

Tags: Walter Kirn