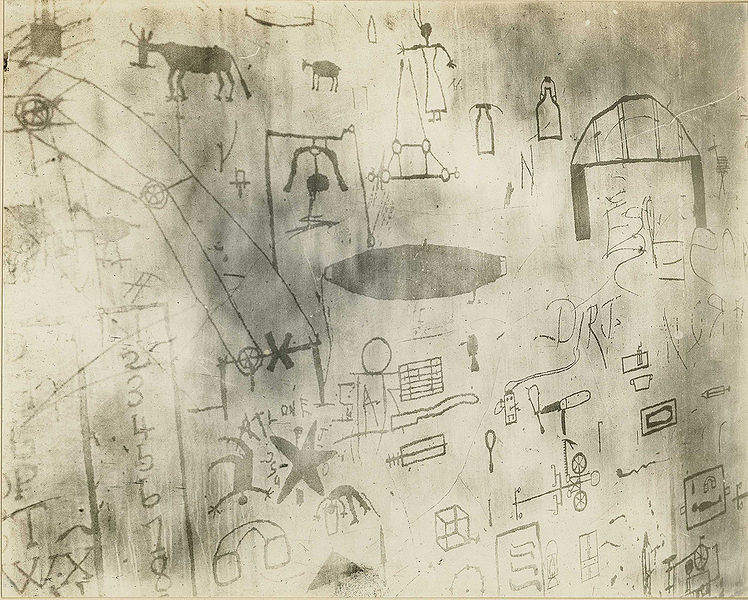

Rhinoplasty performed in Essex, Germany, in 1895. (Image by Klaus D.Peter.)

The still-novel idea of modern cosmetic surgery is enthusiastically broached in this September 24, 1896 article from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which was a reprinted piece from the London Mail. It’s subtitled, “Wonderful Possibilities Are Now Open to Modern Surgery.” An excerpt:

“The latest developments of modern surgical science are making it evident that good looks are no longer to be confined to those with a heritage to them, but may be purchased on the open market. It will, no doubt, be good news to the unhappy possessor of an uncompromising snub nose to be made acquainted with the fact that, for a fairly respectable sum of money, his nasal appendage can be converted into a thorough going aristocratic Wellington, with no nonsense about it, and the spinster lady, whose proboscis is of the parrot type, and whose matrimonial chances have constantly suffered, will hail with a good deal of satisfaction and possibly renewed hope the statement that a generous fee to the facial surgeon will transform the offending organ into the dearest of little Grecians in the world, while an extra payment will secure for her two or three coquettish dimples on the cheeks and chin.

The science of facial surgery is, of course, not exactly a new one. Experiments without number have been made in the London and continental hospitals for many years past. It is not very long ago that the operation of making a very decently formed nose for a young woman whose face had been mutilated in an accident was successfully performed at the Royal Free Hospital. The breastbone of a blackbird was cleverly inserted into the cartilage of the nose and the skin deftly drawn over it and sewn with such neatness that in a short time the seams made by the surgical needle completely healed.

(Image by André Koehne.)

As might be expected, facial surgery came to us from America. There it is practiced in every large town, while a college for its special study exists near Philadelphia, granting diplomas and degrees for proficiency–genuine ones, too, it should be added.

That the science will make its way in England there is not much room for doubt. Already a private doctor living not a hundred miles from Bond street is making quite a reputation in the direction of facial surgery, and his handsome consulting rooms are thronged each day with crowds of wealthy patients, who are anxious to personally test his powers, and who go away eminently satisfied with themselves and convinced that if ‘beauty is but skin deep,’ it is a possession worth having, and, worth paying for.

So far, only those with the most unlimited purses are able to avail themselves of the doctor’s ability, the operations are of such a delicate nature, and require so much technical knowledge, mechanical skill, self-possession and nerve on the part of the operator, that no patient can grudge a generous fee.

The sensitive man, with a wart on the end of his nose, for instance, goes through life full of trembling self-consciousness. He feels that every glance is directed toward the terrible disfigurement, and he becomes nervously apologetic in his general bearing. Imagine what a heavenly vista of happiness and security must unfold itself to such a man, when under the magical knife, that accursed wart disappears forever, and how his gratitude can but be adequately rendered by a substantial expression of it.

Electricity is a useful help to the facial surgeon, and by its aid all kinds of minor blemishes are removed, and tell-tale red noses completely cured.

Electricity is a useful help to the facial surgeon, and by its aid all kinds of minor blemishes are removed, and tell-tale red noses completely cured.

The only drawback to obtaining a really complete transformation is the possibility of the question of identification arising. One can imagine the unenviable position of the man who, in the absence of his wife and family at the seaside, takes the opportunity of considerably improving his appearance by exchanging a somewhat bulbous nose of a deep shade for one of clear-cut and classical proportions, being confronted with the unfeigned astonishment of the partner of his bosom, and, perhaps. repudiated as ‘not being the man who led her to the altar!’ Such a situation would not be an easy one to solve. The advantages of the science, however, undoubtedly greatly outweigh its disadvantages.”