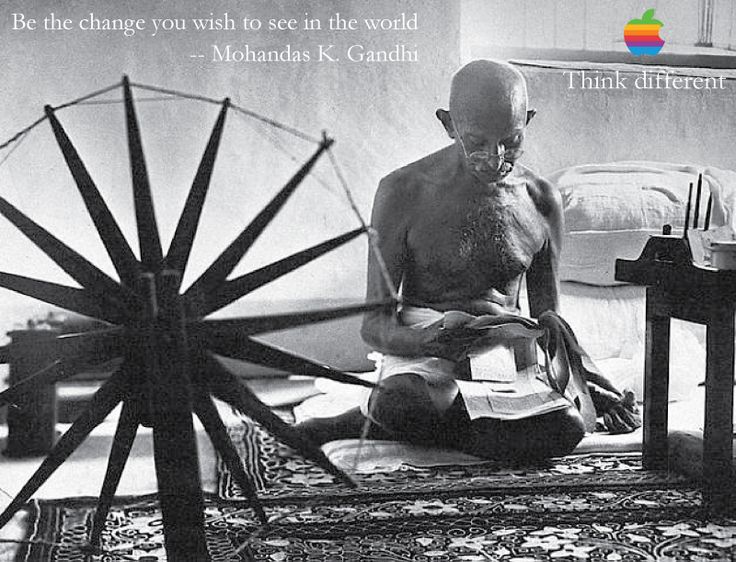

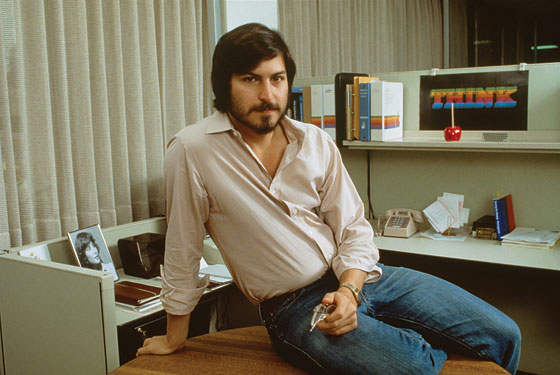

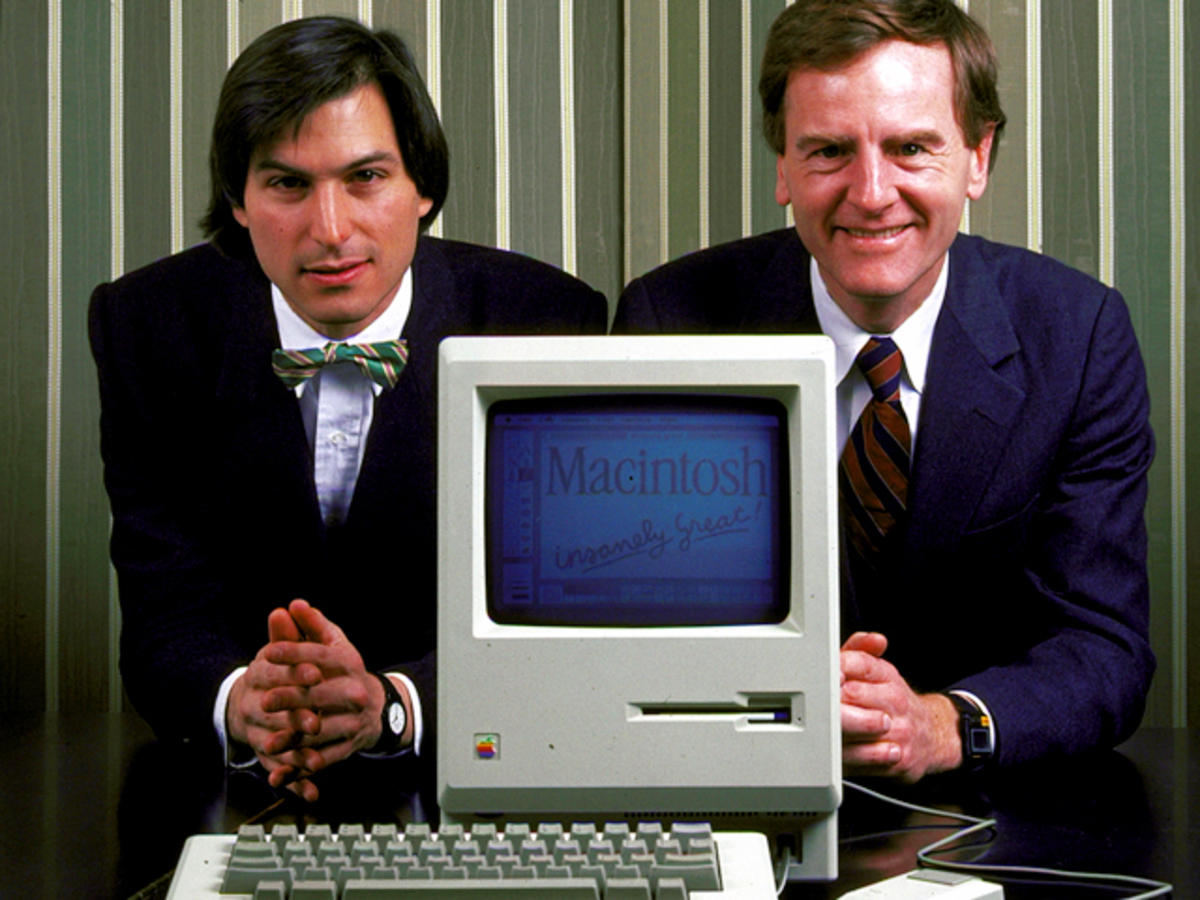

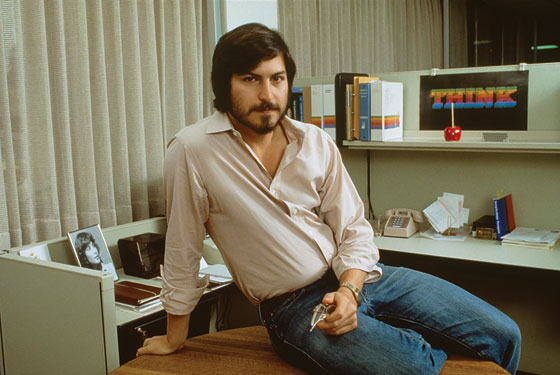

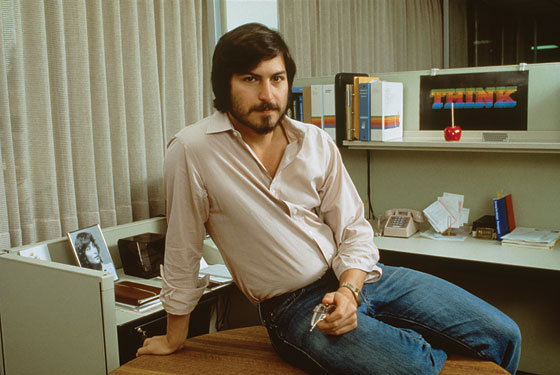

Steve Jobs possessed many great qualities if you could look past the bullying tyrant who disliked philanthropy, which, admittedly, wasn’t easy, but it’s always been tremendously galling that Apple’s grammatically challenged 1997 “Think Different” campaign used Mahatma Gandhi’s likeness to peddle marked-up consumer electronics manufactured by sweatshop labor. Yes, they were really cool computers, but still.

The slain civil rights leader was, of course, a complicated and contradictory character, and no one more ably parried against the simple-headed sanctification and commodification of him than Salman Rushdie did in a Time essay published a year after the ad was launched. The opening:

A thin Indian man with not much hair sits alone on a bare floor, wearing nothing but a loincloth and a pair of cheap spectacles, studying the clutch of handwritten notes in his hand. The black-and-white photograph takes up a full page in the newspaper. In the top left-hand corner of the page, in full color, is a small rainbow-striped apple. Below this, there’s a slangily American injunction to “Think Different.” Such is the present-day power of international Big Business. Even the greatest of the dead may summarily be drafted into its image ad campaigns. Once, a half-century ago, this bony man shaped a nation’s struggle for freedom. But that, as they say, is history. Now Gandhi is modeling for Apple. His thoughts don’t really count in this new incarnation. What counts is that he is considered to be “on message,” in line with the corporate philosophy of Apple.

The advertisement is odd enough to be worth dissecting a little. Obviously it is rich in unintentional comedy. M.K. Gandhi, as the photograph itself demonstrates, was a passionate opponent of modernity and technology, preferring the pencil to the typewriter, the loincloth to the business suit, the plowed field to the belching manufactory. Had the word processor been invented in his lifetime, he would almost certainly have found it abhorrent. The very term word processor, with its overly technological ring, is unlikely to have found favor.

“Think Different.” Gandhi, in his younger days a sophisticated and Westernized lawyer, did indeed change his thinking more radically than most people do. Ghanshyam Das Birla, one of the merchant princes who backed him, once said, “He was more modern than I. But he made a conscious decision to go back to the Middle Ages.” This is not, presumably, the revolutionary new direction in thought that the good folks at Apple are seeking to encourage.

Gandhi today is up for grabs. He has become abstract, ahistorical, postmodern, no longer a man in and of his time but a freeloading concept, a part of the available stock of cultural symbols, an image that can be borrowed, used, distorted, reinvented to fit many different purposes, and to the devil with historicity or truth.

Richard Attenborough’s much-Oscared movie Gandhi struck me, when it was first released, as an example of this type of unhistorical Western saintmaking. Here was Gandhi-as-guru, purveying that fashionable product, the Wisdom of the East; and Gandhi-as-Christ, dying (and, before that, frequently going on hunger strike) so that others might live. His philosophy of nonviolence seemed to work by embarrassing the British into leaving; freedom could be won, the film appeared to suggest, by being more moral than your oppressor, whose moral code could then oblige him to withdraw.

But such is the efficacy of this symbolic Gandhi that the film, for all its simplifications and Hollywoodizations, had a powerful and positive effect on many contemporary freedom struggles. South African antiapartheid campaigners and democratic voices all over South America have enthused to me about the film’s galvanizing effects. This posthumous, exalted “international Gandhi” has apparently become a totem of real inspirational force.

The trouble with the idealized Gandhi is that he’s so darned dull, little more than a dispenser of homilies and nostrums (“An eye for an eye will make the whole world go blind”) with just the odd flash of wit (asked what he thought of Western civilization, he gave the celebrated reply, “I think it would be a great idea”). The real man, if it is still possible to use such a term after the generations of hagiography and reinvention, was infinitely more interesting, one of the most complex and contradictory personalities of the century.•