Now five decades old, the thought experiment known as the Trolley Problem is experiencing new relevance due to the emergence of driverless cars and other robotized functions requiring aforethought about potential moral complications. Despite criticisms about the value of such exercises, I’ve always found them useful and including them in the conversation about autonomous designs surely can’t hurt.

Lauren Cassani Davis of the Atlantic looks at the merging of a stately philosophical scenario and cutting-edge technology. An excerpt about Stanford mechanical engineer Chris Gerdes:

Gerdes has been working with a philosophy professor, Patrick Lin, to make ethical thinking a key part of his team’s design process. Lin, who teaches at Cal Poly, spent a year working in Gerdes’s lab and has given talks to Google, Tesla, and others about the ethics of automating cars. The trolley problem is usually one of the first examples he uses to show that not all questions can be solved simply through developing more sophisticated engineering. “Not a lot of engineers appreciate or grasp the problem of programming a car ethically, as opposed to programming it to strictly obey the law,” Lin said.

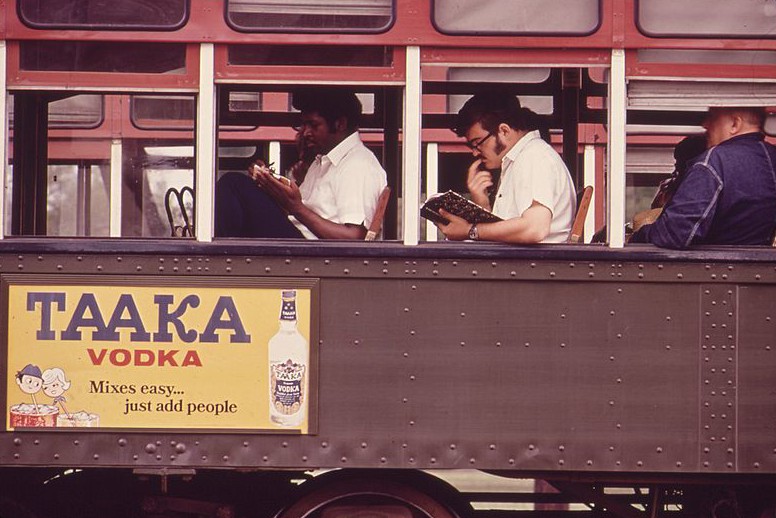

But the trolley problem can be a double-edged sword, Lin says. On the one hand, it’s a great entry point and teaching tool for engineers with no background in ethics. On the other hand, its prevalence, whimsical tone, and iconic status can shield you from considering a wider range of dilemmas and ethical considerations. Lin has found that delivering the trolley problem in its original form—streetcar hurtling towards workers in a strangely bare landscape—can be counterproductive, so he often re-formulates it in terms of autonomous cars:

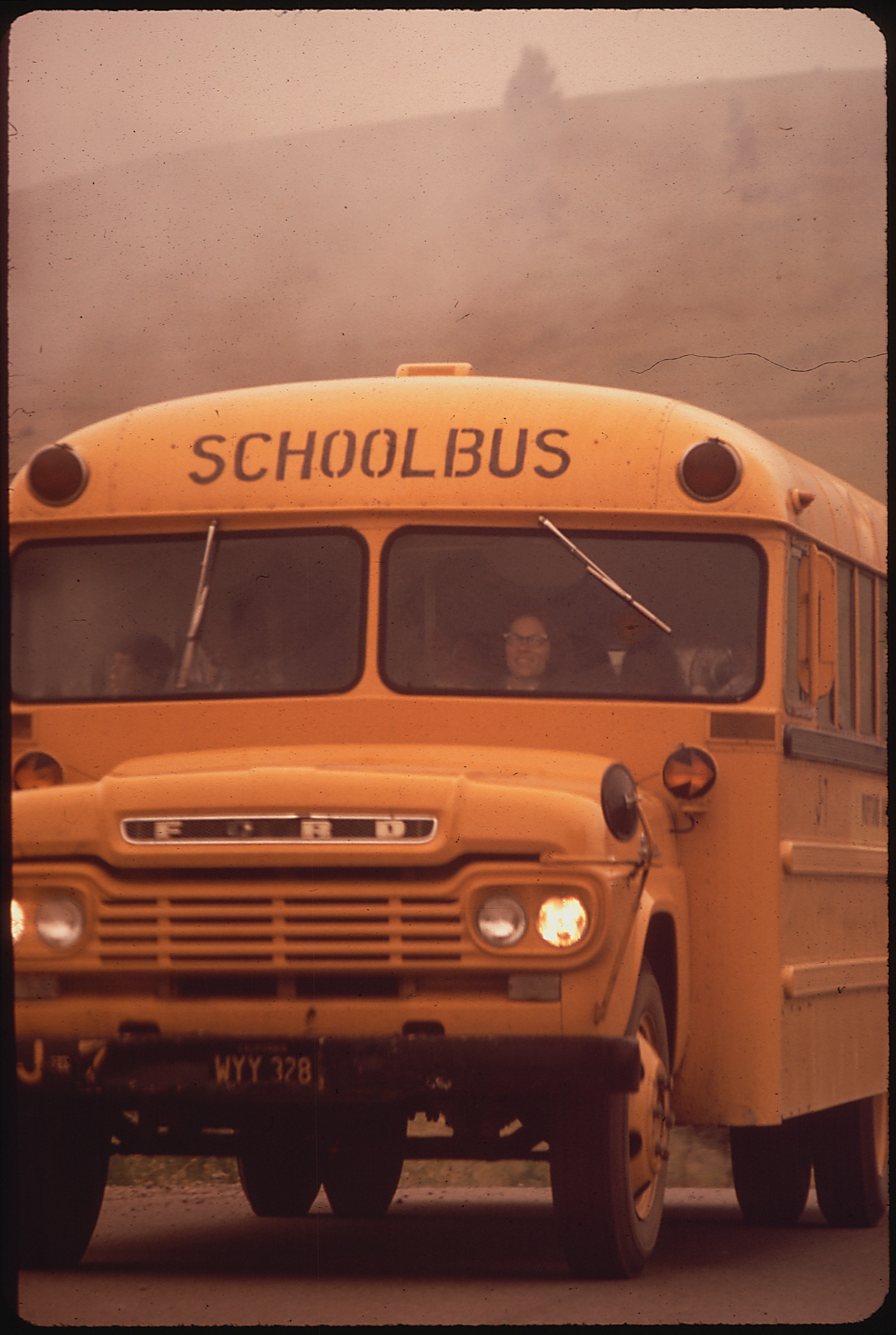

You’re driving an autonomous car in manual mode—you’re inattentive and suddenly are heading towards five people at a farmer’s market. Your car senses this incoming collision, and has to decide how to react. If the only option is to jerk to the right, and hit one person instead of remaining on its course towards the five, what should it do?

It may be fortuitous that the trolley problem has trickled into the world of driverless cars: It illuminates some of the profound ethical—and legal—challenges we will face ahead with robots. As human agents are replaced by robotic ones, many of our decisions will cease to be in-the-moment, knee-jerk reactions. Instead, we will have the ability to premeditate different options as we program how our machines will act.•