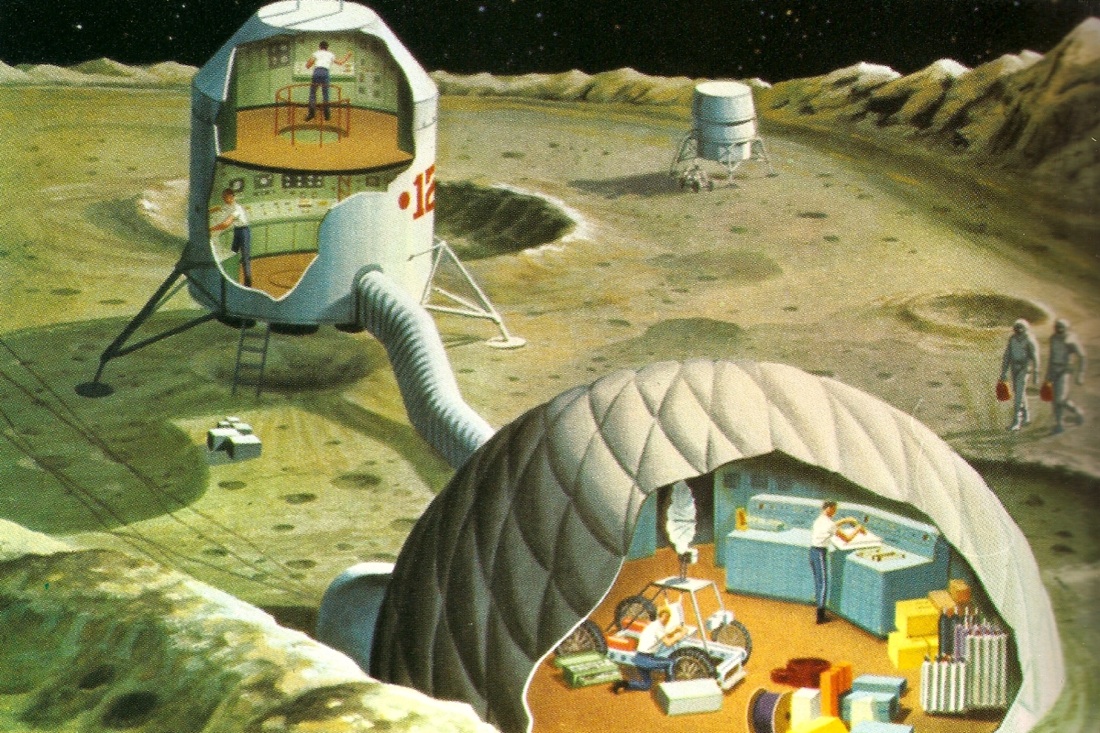

Much has already been written abut the jaw-dropping discovery of “another Earth” near Proxima Centauri, something that seemed likely to happen sooner or later and has now occurred. My favorite words on the topic were penned by Olaf Stampf of Spiegel. He understands the magnitude of the finding while cautioning that even with the development of fusion propulsion, reaching our sister planet in a reasonable time frame is still a bridge too far. Perhaps it’s a better-than-ever time for the human-less probes to Alpha Centauri suggested by Ken Kalfus and being developed by Yuri Milner, with their destination shortened by just a bit. Presently, pretty much all space exploration should be handled by machines, anyhow.

The opening:

The faraway world exists in constant twilight. Although its nearby blood-red dwarf star only provides one tiny fraction of our sun’s light, its warmth might still be enough to create a life-sustaining climate.

But is there really life on this newly detected planet? Nobody knows — at least not yet. Only one thing is certain: Because of the darkness, animals and plants would look different from the ones we know from Earth. Trees and shrubs would have pitch-black leaves, as if they’d been burned. The alien flora would need to be darkly colored to use the dim starlight for its photosynthesis.

And what about higher forms of life, like animals or intelligent beings? It’s very possible that exotic organisms exist on the planet. Given that it is several million years older than the Earth, it would have had enough time for life to develop.

On the other hand, it would also have to repeatedly withstand hellish conditions. Its sun is a so-called flare star, a cosmic fire-breather that tends to produce apocalyptic eruptions of plasma. All of the planet’s oceans, rivers and lakes may well have long since evaporated.

The newly discovered planet doesn’t yet have a name, but the red dwarf star around which it circles is famous: Proxima Centauri, our nearest fixed star, only 4.24 lightyears away — our sun’s closest neighbor.

That’s what makes this finding so scientifically exciting.•