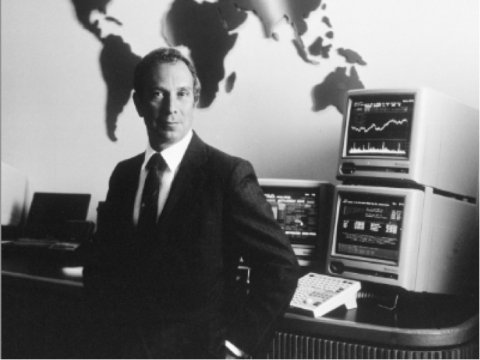

Being great at one thing doesn’t necessarily mean you possess any general genius (e.g., Ben Carson, neurosurgeon). Michael Bloomberg believed the financial sector needed a certain type of information terminal and he created it with a ridiculous $10 million golden parachute he was handed after getting shitcanned by Salomon Brothers. About the terminals, he was right. It made him one of the richest people in the world, but his wealth should never have been taken as a sign of competence or rectitude.

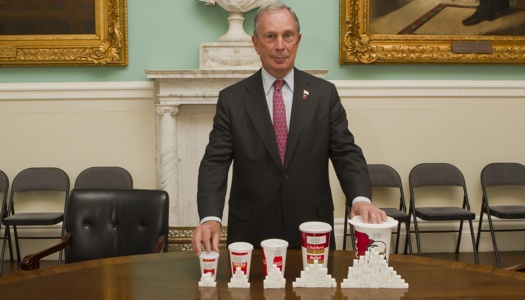

As Mayor of New York, he did some great things and bungled major projects like Build It Back. He was tone deaf enough to want to proceed with the marathon in the wake of Hurricane Sandy turning New York City into a necropolis. Crime was kept low but policing got out of hand on his watch. The poorer people he claimed to champion often did worse. His paternalism knew no bounds, often seeming petty. He even scammed a third term, writing his own law in a back-office deal with another billionaire, voters be damned.

As a businessperson, Bloomberg is likewise a mixed bag. Unencumbered with the mayoralty, he’s returned to his namesake business, slicing and dicing his way through the journalistic side, an area for which he holds no great regard. All the while, those terminals keep updating, making general rightness or wrongness seem almost irrelevant on a large scale but often troubling on the micro one.

From Isabell Huelsen and Holger Stark at Spiegel:

Visitors to the building could be forgiven for thinking that the heyday of journalism was still ongoing. Staff exit the elevator into a light-filled foyer that feels like the lobby of a designer hotel. The eye is drawn to orange sofas and white lacquered counters, upon which rest bowls stuffed with apples, oranges and diced melon. There are carrot sticks and broccoli, as well as fresh roasted coffees that would put any Starbucks to shame. The employees scurrying by can help themselves free of charge. Bloomberg wants his people to be comfortable.

But his paternalism can at times seem condescending. The potato chip bags are free, but they’re only available in the smallest size possible. Bloomberg would like his people to eat healthily. And the elevators don’t stop on each of the building’s 25 floors — only on those marked with a white circle — forcing employees to take the stairs.

In nearly every Bloomberg bureau around the world there is at least one saltwater aquarium with purple and yellow fish and corals — to foster relaxation, Bloomberg says. Those who work for him should be proud of their job. One of his favorite sentences is: “The best for us.”

‘Scientology on Speed’

Those who jump ship, though, get a taste of his colder side. Bloomberg once confessed that he doesn’t attend going-away parties out of principle, saying that he couldn’t wish departing employees all the best. “That just wouldn’t be honest of me,” he said. Whoever turns his or her back on the company is no longer one of us, but one of “them.” Bloomberg’s employees must enter a binding contractual agreement to not divulge company secrets, including a clause that permits the company to scan an employee’s e-mails even after that person has left. The microcosm of Mike Bloomberg is a whimsical world of good and evil, one with its own unique — some might say sect-like — view of things. An insider jokingly refers to it as “Scientology on speed.”•