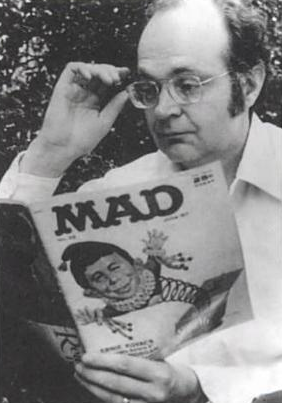

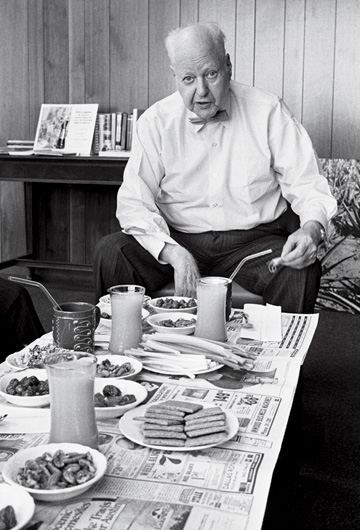

People in show business are often labeled “genius” if they’re able to complete a sudoku slightly faster than Heidi Klum. But Ricky Jay is the real deal, a deeply brilliant person who can accomplish amazing things with his brain despite the deterioration of some basic neurological functions. A clip of the magician, actor and scholar appearing with Merv Griffin in 1983 and then an excerpt from Mark Singer’s great 1993 New Yorker profile, “Secrets of Magus.”

“Jay has an anomalous memory, extraordinarily retentive but riddled with hard-to-account-for gaps. ‘I’m becoming quite worried about my memory,’ he said not long ago. ‘New information doesn’t stay. I wonder if it’s the NutraSweet.’ As a child, he read avidly and could summon the title and the author of every book that had passed through his hands. Now he gets lost driving in his own neighborhood, where he has lived for several years—he has no idea how many. He once had a summer job tending bar and doing magic at a place called the Royal Palm, in Ithaca, New York. On a bet, he accepted a mnemonic challenge from a group of friendly patrons. A numbered list of a hundred arbitrary objects was drawn up: No. 3 was ‘paintbrush,’ No. 18 was ‘plush ottoman,’ No. 25 was ‘roaring lion,’ and so on. ‘Ricky! Sixty-five!’ someone would demand, and he had ten seconds to respond correctly or lose a buck. He always won, and, to this day, still would. He is capable of leaving the house wearing his suit jacket but forgetting his pants. He can recite verbatim the rapid-fire spiel he delivered a quarter of a century ago, when he was briefly employed as a carnival barker: ‘See the magician; the fire ‘manipulator’; the girl with the yellow e-e-elastic tissue. See Adam and Eve, boy and girl, brother and sister, all in one, one of the world’s three living ‘morphrodites.’ And the e-e-electrode lady . . .’ He can quote verse after verse of nineteenth-century Cockney rhyming slang. He says he cannot remember what age he was when his family moved from Brooklyn to the New Jersey suburbs. He cannot recall the year he entered college or the year he left. ‘If you ask me for specific dates, we’re in trouble,’ he says.”