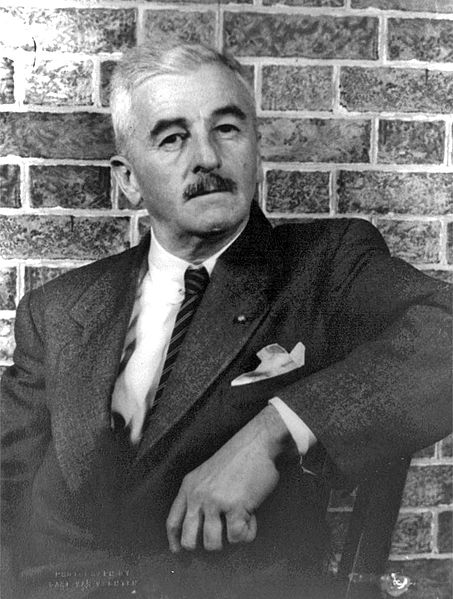

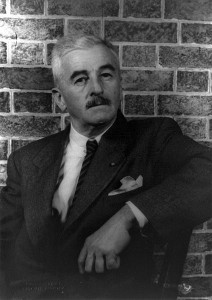

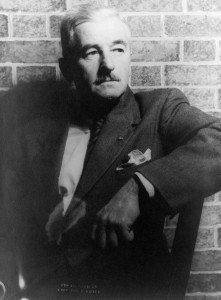

William Styron attended his idol William Faulkner’s 1962 funeral and filed a report for Life. The opening of the questionably titled, “As He Lay Dead, a Bitter Grief“:

“He detested more than anything the invasion of his privacy. Though I am made to feel welcome in the house by Mrs. Faulkner and by his daughter, Jill, and though I know that the welcome is sincere, I feel an intruder nonetheless. Grief, like few things else, is a private affair. Moreover, Faulkner hated those (and there were many) who would poke about in his private life–literary snoops and gossips yearning for the brief glimpse of propinquity with greatness and a mite of reflected fame. He had said himself more than once, quite rightly, that the only thing that should matter to other people about a wirter is his books. Now that he is dead and helpless in a gray wooden coffin. I feel even more an interloper, prying around in a place I should not be.

But the first fact of the day, aside from that final fact of a death which has so diminished us, is the heat, and it is a heat which is like a small mean death itself, as if one were being smothered to extinction in a damp woolen overcoat. Even the newspapers in Memphis, 60 miles to the north, have commented on the ferocious weather. Oxford lies drowned in heat, and the feeling around the courthouse square on this Saturday forenoon is a hot, sweaty languor bordering on desperation. Parked slantwise against the curb, Fords and Chevrolets and pickup trucks bake in merciless sunlight. People in Mississippi have learned to move gradually, almost timidly, in this climate. They walk with both caution and deliberation. Beneath the portico of the First National Bank and around the scantily shaded walks around the courthouse itself, the traffic of shirtsleeved farmers and dewy-browed housewives and marketing Negroes is listless and slow moving. Painted high up against the side of a building to the west of the courthouse and surmounted by a painted Confederate flag is a huge sign at least 20 feet long reading ‘Rebel Cosmetology College.’ Sign, flag and wall, dominating one hot angle of the square, are caught in blazing light and seem to verge perilously close to combustion. It is a monumental heat, heat so desolating to the body and spirit as to have the quality of a half-remembered bad dream, until one realizes that it has, indeed, been encountered before, in all these novels and stories of Faulkner through which this unholy weather–and other weather more benign–moves with almost touchable reality.”

••••••••••

Read also: