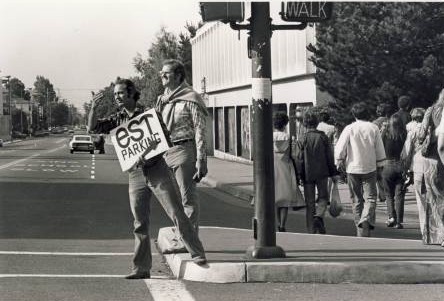

Werner Erhard, the shouting est salesman, is still working it, though opinions will vary on what it is.

When you’re born John Rosenberg, rechristen yourself after a Nazi rocketeer (misspelling it!), and unabashedly tell people that you’re a hero, you may be questionable. Nonetheless, the profane self-help peddler who came to wide prominence in the 1970s, with the aid of apostles in entertainment and intellectual circles, from John Denver to Buckminster Fuller, continues apace at 80 and has reinvented himself yet again, after nearly being permanently knocked from his pedestal by health issues, an IRS imbroglio, a shattering 60 Minutes profile and ongoing gamesmanship with Scientologists.

A really fun New York Times piece by Peter Haldeman looks at the latest Erhard iteration, while offering an alternative version of how the Dale Carnegie of sleep deprivation came to rename himself. The opening:

The silver-haired man dressed like a waiter (dark vest, dark slacks) paced the aisle between rows of desks in a Toronto conference room. “If you’re going to be a leader, you’re going to have to have a very loose relationship with this thing you call ‘I’ or ‘me,’” he shouted. “Maybe that whole thing in me around which the universe revolves isn’t so central!”

He paused to wipe his brow with a wad of paper towels. An assistant stood by with a microphone, but he waved her off. “Maybe life is not about the self but about self-transcendence! You got a problem with that?”

No one in the room had a problem with that. The desks were occupied by 27 name-tagged academics from around the world. And in the course of the day, a number of them would take the mike to pose what their instructor referred to as “yeah buts, how ’bouts or what ifs” in response to his pronouncements — but no one had a problem with them.

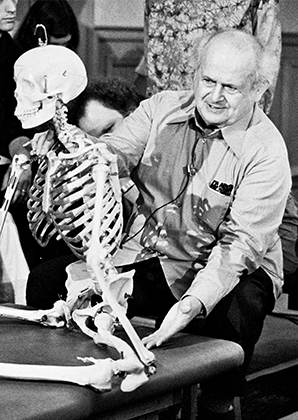

In some ways, the three-day workshop, “Creating Class Leaders,” recalled an EST training session. As with that cultural touchstone of the 1970s, there was “sharing” and applause. There were confrontations and hugs. Gnomic declarations hovered in the air like mist: “We need to distinguish distinction”; “There’s no seeing, there’s only the seer”; “There isn’t any is.”

But the event was much more civilized than EST. There were bathroom breaks. No one was called an expletive by the teacher.

This is significant because the teacher was none other than the creator of EST, Werner Erhard.•

__________________________

In 1973, Denver, substitute host on the Tonight Show, invited his guru to chat.