Walter Isaacson, who’s writing a book about Silicon Valley creators, knows firsthand that sometimes such people take credit that may not be coming to them. So he’s done a wise thing and put a draft of part of his book online, so that crowdsourcing can do its magic. As he puts it: “I am sketching a draft of my next book on the innovators of the digital age. Here’s a rough draft of a section that sets the scene in Silicon Valley in the 1970s. I would appreciate notes, comments, corrections.” The opening paragraphs of his draft at Medium:

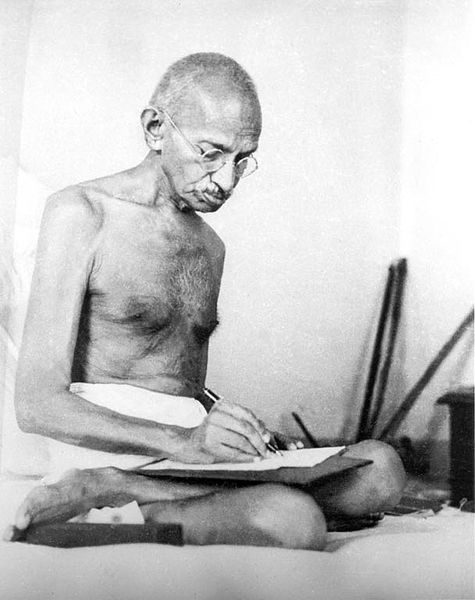

“The idea of a personal computer, one that ordinary individuals could own and operate and keep in their homes, was envisioned in 1945 by Vannevar Bush. After building his Differential Analyzer at MIT and helping to create the military-industrial-academic triangle, he wrote an essay for the July 1945 issue of the Atlantic titled ‘As We May Think.’ In it he conjured up the possibility of a personal machine, which he dubbed a memex, that would not only do mathematical tasks but also store and retrieve a person’s words, pictures and other information. ‘Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library,’ he wrote. ‘A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.’

Bush imagined that the device would have a ‘direct entry’ mechanism so you could put information and all your records into its memory. He even predicted hypertext links, file sharing, and collaborative knowledge accumulation. ‘Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified,’ he wrote, anticipating Wikipedia by a half century.

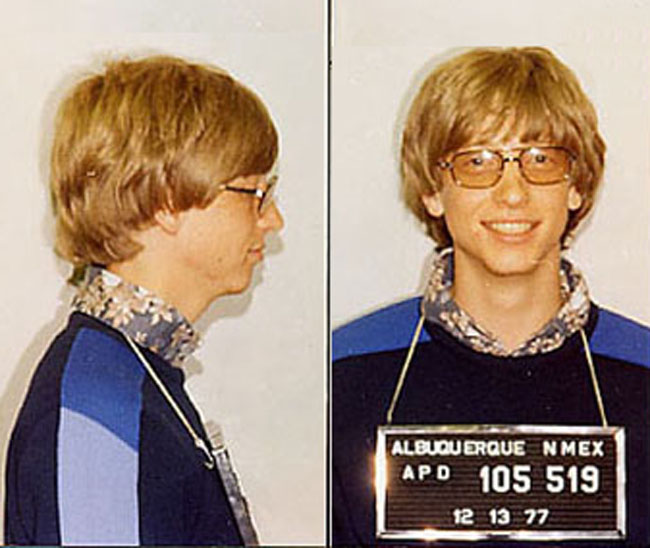

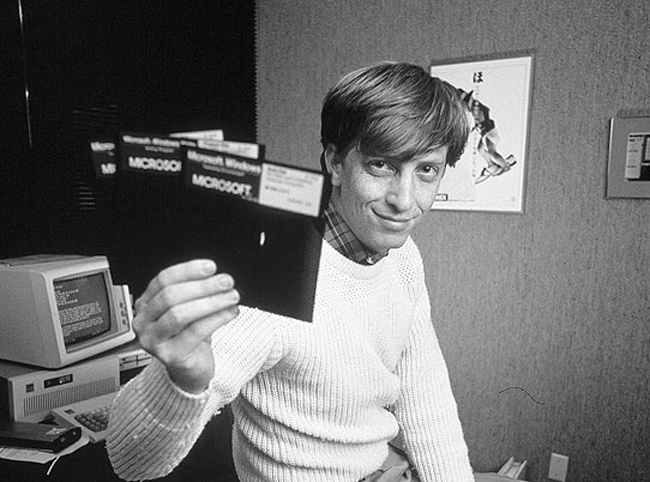

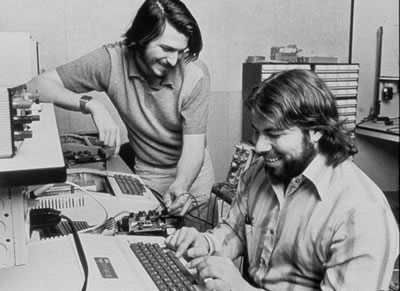

As it turned out, computers did not evolve the way that Bush envisioned, at least not initially. Instead of becoming personal tools and memory banks for individuals to use, they became hulking industrial and military colossi that researchers could time share but the average person could not touch. In the early 1970s, companies such as DEC began to make minicomputers, the size of a small refrigerator, but they dismissed the idea that there would be a market for even smaller ones that could be owned and operated by ordinary folks. ‘I can’t see any reason that anyone would want a computer of his own,’ DEC president Ken Olsen declared at a May 1974 meeting where his operations committee was debating whether to create a smaller version of its PDP-8 for personal consumers. As a result, the personal computer revolution, when it erupted in the mid-1970s, was led by scruffy entrepreneurs who started companies in strip malls and garages with names like Altair and Apple.

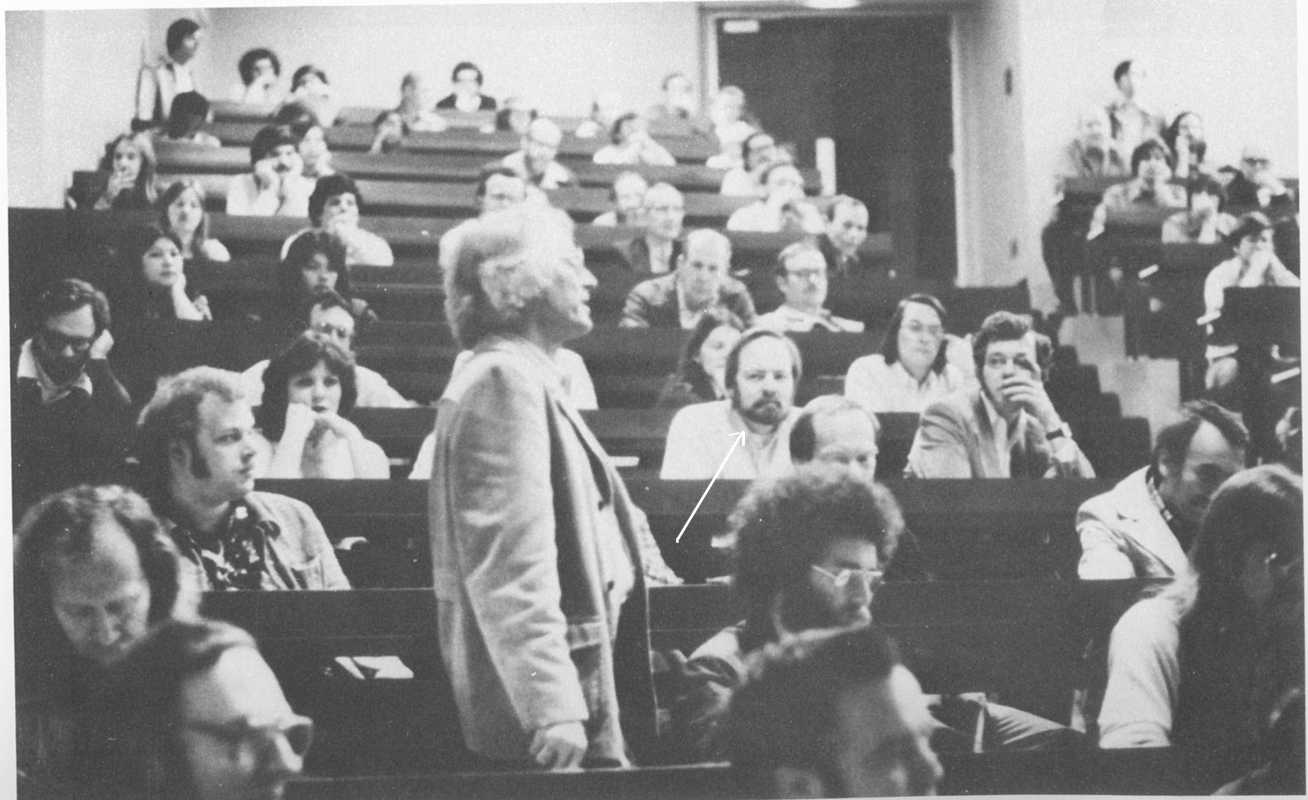

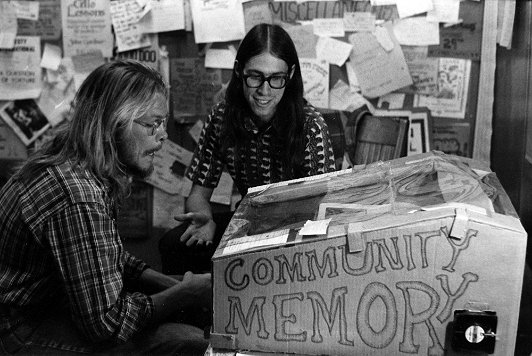

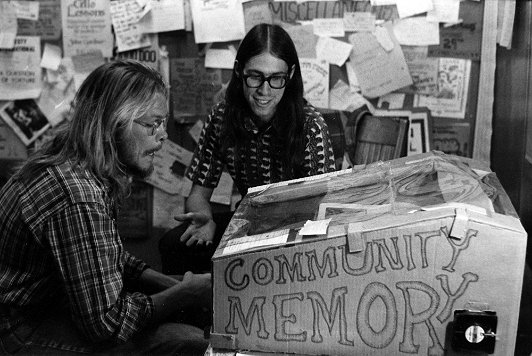

Once again, innovation was spurred by the right combination of technological advances, new ideas, and social desires. The development of the microprocessor, which made it technologically possible to invent a personal computer, occurred at a time of rich cultural ferment in Silicon Valley in the late 1960s, one that created a cauldron suitable for homebrewed machines. There was the engineering culture that arose during World War II with the growth of defense contractors, such as Westinghouse and Lockheed, followed by electronics companies such as Fairchild and its fairchildren. There was the startup culture, exemplified by Intel and Atari, where creativity was encouraged and stultifying bureaucracies disdained. Stanford and its industrial park had lured west a great silicon rush of pioneers, many of them hackers and hobbyists who, with their hands-on imperative, had a craving for computers that they could touch and play with. In addition there was a subculture populated by wireheads, phreakers, and cyberpunks, who got their kicks hacking into the Bell System’s phone lines or the timeshared computers of big corporations.

Added to this mix were two countercultural strands: the hippies, born out of the Bay Area’s beat generation, and the antiwar activists, born out of the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley. The antiauthoritarian and power-to-the-people mindset of the late 1960s youth culture, along with its celebration of rebellion and free expression, helped lay the ground for the next wave of computing. As John Markoff wrote in What the Dormouse Said, ‘Personal computers that were designed for and belonged to single individuals would emerge initially in concert with a counterculture that rejected authority and believed the human spirit would triumph over corporate technology.'”