The photojournalist Mary Ellen Mark, best known for Streetwise, just passed away at 75. In 1987, Vicki Goldberg penned a longform NYT portrait of Mark, whose career ascended as documentary photography in print was being elbowed aside by pictures of celebrities with perfect teeth. Her sojourns inside brothels and hospices and gypsy camps and squats raised the old question about people who carry cameras into squalid corners–those of exploitation. These risky assignments improved Mark’s station in life, but how about her subjects? I feel certain we’re better for her work, even if a lone journalist, no matter how gifted and determined, can seldom counteract injustices we’ve unloosed upon the world.

An excerpt from Goldberg:

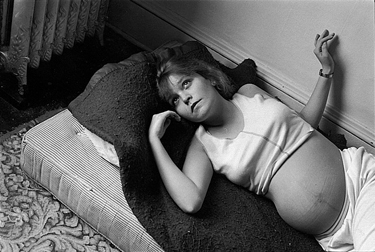

WHENEVER SHE PICKS UP A camera, Mark, 47, puts herself in an emotional no-man’s land. She claims that she doesn’t take risks–”War photographers do that”–yet hers is the archetypal saga of the photojournalist who conquers obstacles and emotional shock to bring back accounts of unexplored territory: hospices for the dying, brothels in India, camps for children with cancer.

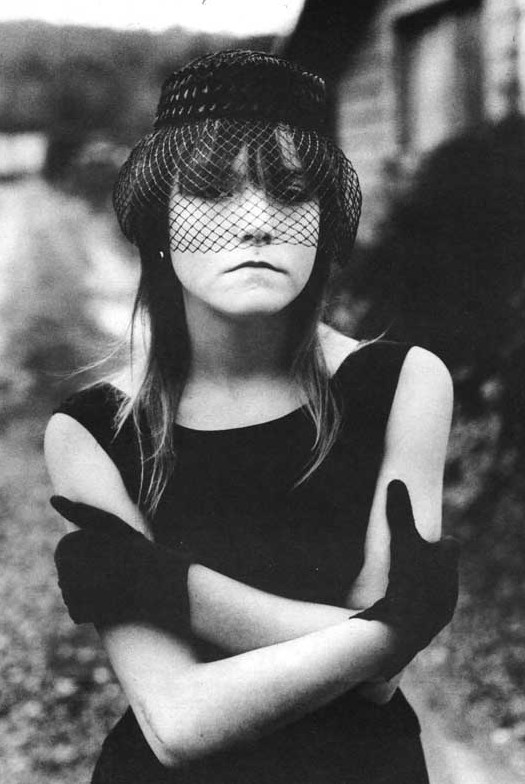

She brings to all her photographs an unflinching yet compassionate eye. In the midst of exotica or on the fringes of society, where she often chooses to be, she does not exaggerate the unavoidably alien, freakish qualities a less complex photographer would emphasize, but tries to find clues to what is familiar and human. Thus a picture of three Indian prostitutes solemnly, uncomfortably awaiting a man’s decision becomes a poignant, harsher version of young girls at a dance. Mark says that Falkland Road, her 1981 book on the Bombay brothels ”was meant almost as a metaphor for entrapment, for how difficult it is to be a woman.”

Her subject matter raises an old question about photojournalism: Do photographers exploit those less fortunate than themselves for the sake of their art? Mark herself simply asks whether the poor should be ignored; many have eagerly posed for her, she says, precisely because they wished to be noticed at last. And as Richard B. Stolley, who as managing editor of Life magazine assigned to Mark many of her most important stories, puts it, ”If she weren’t such a good photographer, the charge would never arise.”

MARK ASSISTED HER HUSBAND, the film maker Martin Bell, on Streetwise, a documentary about homeless teen-agers she had photographed in Seattle. The film was nominated for an Academy Award. Her own honors include the University of Missouri’s top award for a feature picture story (twice), the Page One Award, the Leica Medal of Excellence, the Canon Photo Essayist Award, the Robert F. Kennedy Award (twice), the Philippe Halsman Award and numerous grants. She belongs on any list of top contemporary photojournalists with the likes of James Nachtwey, Sebastiao Salgado and David Burnett. Stolley refers to her as ”one of the top three or four in the world” and adds, ”she is probably the best – how can I put this without sounding sexist? – I don’t know of another woman photojournalist as good as she is now.”

Photojournalism has recently scaled new heights of public esteem. Museums and galleries lavishly display pictures that were previously seen only in print. Films like Under Fire and Salvador set the photojournalist on center stage and biographies of past masters assure that the legendary glamour shines on.

Yet at a time when magazines are cutting back on photo essays in favor of twinkling pictures of media stars and token illustrations in text pieces, outlets for photojournalism are steadily diminishing. Mary Ellen Mark is one of the few photographers today whose stories have regularly appeared in such publications as Life, The Sunday Times of London, The New York Times Magazine, Rolling Stone, Paris-Match, Stern and Time. And in a magazine forum that sometimes seems to be split between hardship and glitz, she has an offbeat and distinctive vision of both. She does essays on Ethiopian refugees or the elderly in Miami; then, to earn a living, she takes advertising and publicity stills for films and countless celebrity portraits.•