Reassessment–a chastening, even–often attends the publication of a biography, especially in the cases of writers or politicians. Joan Didion’s received a surprising number of calls for impeachment with the publication of Tracy Daugherty’s book about her.

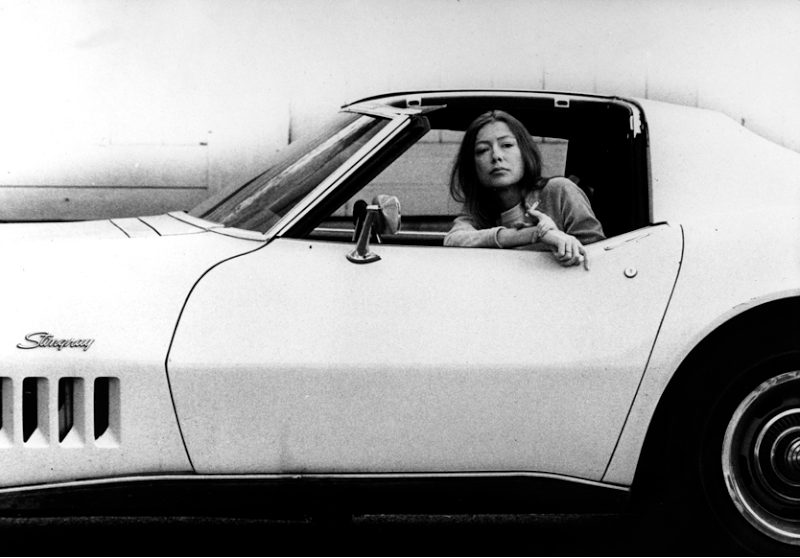

I’ve never been a fan of Play It As It Lays (leave the smut to the professionals, please), but Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album are sensational (in the best sense of the word). Yes, Didion was a fashion-magazine veteran savvy enough to wear cool sunglasses and pose at the wheel of her Stingray, but her efforts at auto-iconography don’t even rate when compared to, say, Hunter S. Thompson’s. Since they both had the chops, who even cares?

A lot of the backlash stems from the then-aphasiac author’s depiction of California as haywire during the ’60s and ’70s. Her home state, that traitor! Sure, a big-picture take of the fantasia that is California can’t completely satisfy, and perhaps her portrait flattered East Coasters, but maybe most disturbing is that she did land on numerous and troubling truths of that place in that time. Although some will argue that these were mere distortions.

From a very well-written Barnes & Noble review of Daugherty’s bio by Tom Carson, a self-described Didion skeptic:

In her prime, she didn’t have casual readers; her gift for imposing her sensibility on events didn’t permit it. The paradox of The Year of Magical Thinking‘s success was that it introduced her to a nonliterary audience largely unaware that she’d been generating intimations of morbidity, desolation, and the existential jitters out of pretty much any topic put in front of her, from 1968’s career-defining essay collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem on. When “California” still blended the worst of heaven and the best of hell in Noo Yawk intellectuals’ minds, no other writer matched native daughter Didion at being the anti−Beach Boys.

In her home state’s very entertaining transformation from freakish American exotica to the place lit by rockets’ pink glare that the other forty-nine all try to be, she’s a pivotal figure: the last West Coast chronicler to make a career of insisting that where she came from was special, strange, and always latently monstrous. That happened to be precisely the view her culturally unnerved audience wanted endorsed at the time, but Didion also invited derision by treating her perpetually threatened morale as the ultimate gauge of how badly the twentieth century was botching its job. In a memorable hit piece, Barbara Grizzuti Harrison called her “a neurasthenic Cher.” Pauline Kael read Didion’s “ridiculously swank” 1970 novel Play It as It Lays “between bouts of disbelieving giggles.” Maybe not insignificantly, she tends to drive other woman writers up the wall — especially if, like Kael, they’re California gals themselves — more than men, who usually flip for her solemn tension.•

__________________________________

In the 1970s, Tom Brokaw profiled Didion, when she still called California home.