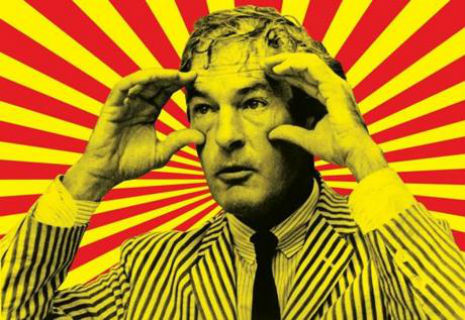

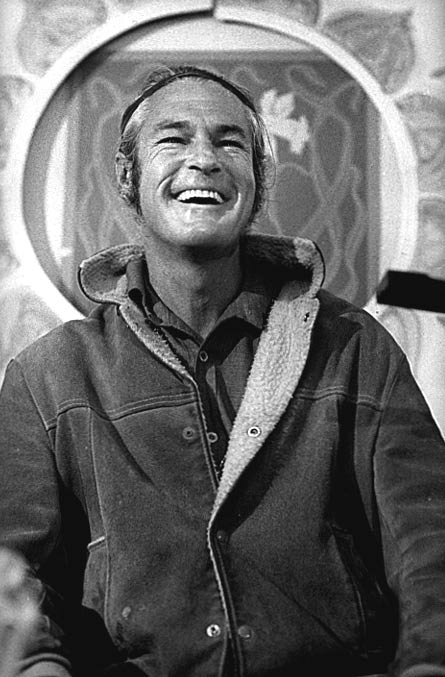

In 1987, two software moguls, Bill Gates and Dr. Timothy Leary, were asked by Omni to make predictions about life 20 years in the future. Gates was more accurate in his prognostications, though Leary provided some gems like this one: “What will you be? A performer. Everyone will be performing.”

________________________

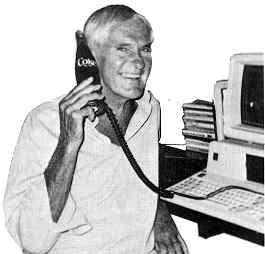

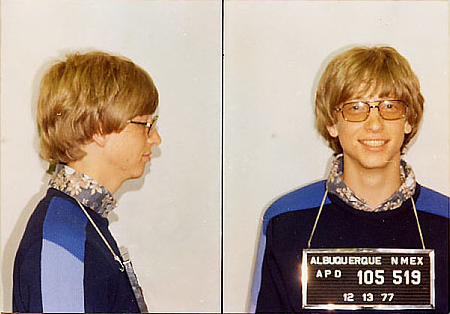

Bill Gates, Chairman of the Board, Microsoft Corporation:

The processing of digital information is improving very quickly. In ten years you’ll have 30 to 40 times as much computational power, and you’ll be able to manipulate the images and sounds that you now receive just passively from TV — you’ll insert yourself into a game or even change the outcome according to your wishes. So in 20 years your ability to get information will be expanded exponentially.

Take one example; You’re sitting at home. You’ll have a variety of image libraries that will contain, say, all the world’s best art. You’ll also have very cheap, flat panel-display devices throughout your house that will provide resolution so good that viewing a projection will be like looking at the original oil. painting. It will be that realistic.

In 20 years the Information Age will be here, absolutely. The dream of having the world database at your fingertips will have become a reality. You’ll even be able to call up a video show and place yourself in it. Today, if you want to create an image on a screen — a beach with the sun and waves— you’ve got to take a picture of it. But in 20 years you’ll literally construct your own images and scenes. You will have stored very high-level representations of what the sun looks like or how the wind blows. If you want a certain movie star to be sitting on a beach, kind of being lazy, believe me, you’ll be able to do that. People are already doing these things.

Also, we will have serious voice recognition. I expect to wake up and say, “Show me some nice Da Vinci stuff,” and my ceiling, a high-resolution display, will show me what I want to see — or call up any sort of music or video. The world will be online, and we’ll be able to simulate just about anything. Let’s say you want to go out to a racetrack. When you wake up you’ll say, “Hey, rent me one of those formula cars in Daytona,” and with some local controls, a little steering wheel you pull out of your drawer, you’ll be able to get the image and feel like you’re driving the car.

There’s a scary question to all this: How necessary will it be to go to real places or do real things? I mean, in 20 years we will synthesize reality. We’ll do it super-realistically and in real time. The machine will check its database and think of some stories you might tell, songs you might sing, jokes you might not have heard before. Today we simply synthesize flight simulation.

A lot of things are going to vanish from our lives. There will be a machine that keys off of physiological traits, whether it’s voiceprint or fingerprint; so in 2007 Mick Jagger will be onstage, and when Mick feels heat, you’ll feel heat. If a spray of water hits Tina on the back, you’ll feel that, too. I hope passive entertainment will disappear. People want to get involved. It will really start to change the quality of entertainment because it will be so individualized. If you like Bill Cosby, then there will be a digital description of Cosby, his mannerisms and appearance, and you will build your own show from that.

People will like the idea that the machine really knows them and that the machine can create experiences formed around the events in their lives to fulfill their particular needs and interests. But there’s a danger, too. It will be easy to feel worthless or overwhelmed by the amount of data. So what we’ll have to do is make sure the machine can tailor the data to the individual.

Probably all this progress will be pretty disruptive stuff. We’ll really find out what the human brain can do, but we’ll have serious problems about the purpose of it all. We’re going to find out how curious we are and how-much stimulation we can take. There have been experiments in which a monkey can choose to ingest cocaine and the monkey keeps on pushing that button until he dies. Well, we are going to create some pretty intense experiences through synthesized video-audio. Do you think you’ll reach a point of satisfaction when you no longer have to try something new or make something better? Life is really going to change; your ability to access satisfying experiences will be so large.

Take the change in movies in the last few years. Just a few years ago you had to find out where the movie was playing, then go to a certain neighborhood and stand in line to see the movie. Now you can go two blocks and find 10,000 titles. You feel inadequate. It’s going to be intimidating.

Twenty years ago I was ten years old. We already had color TV. I didn’t have theories about what the world might be like. But in the next 20 years you won’t be able to extrapolate the rate of progress from any previous pattern or curve because the new chips, these local intelligences that can process information, will cause a warp in what it’s possible to do. The leap will be unique. I can’t think of any equivalent phenomenon in history.•

________________________

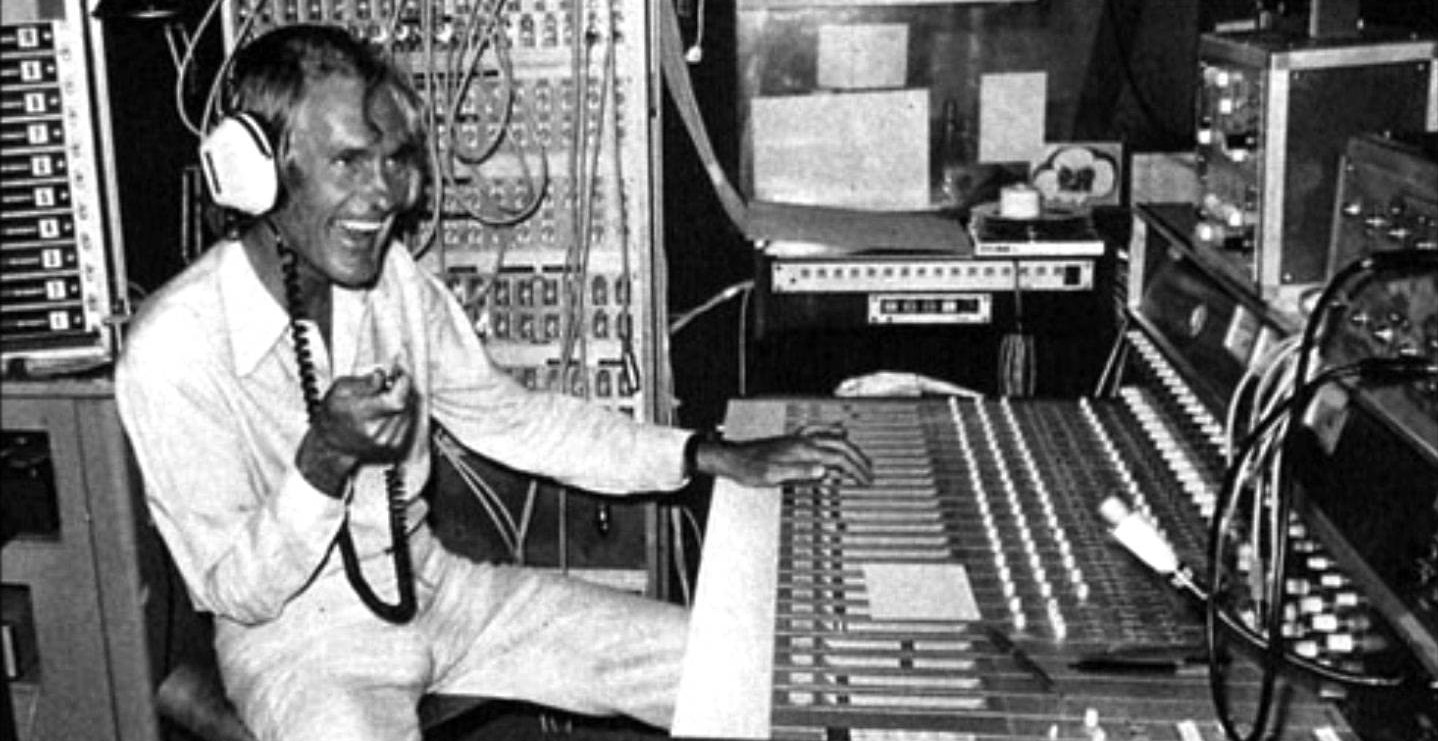

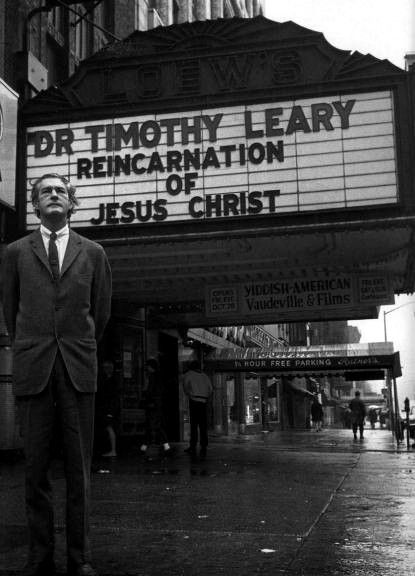

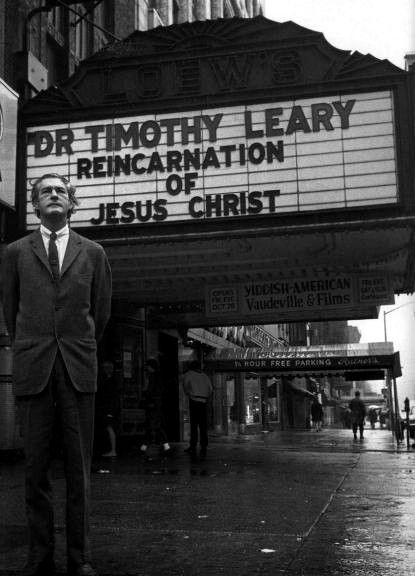

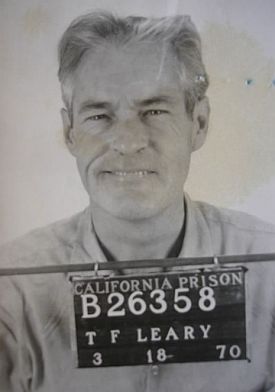

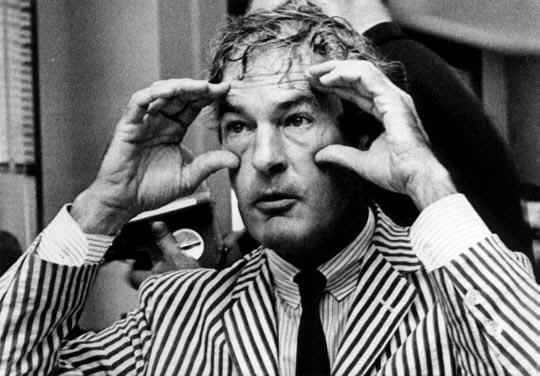

Timothy Leary, President, Futique Software Company:

By 2007 the problem of scarcity will be solved. Because most work will be done by robots and computers, you won’t have to work. Material possessions won’t mean as much to us as they do now, If there are nine Porsches in your garage. you’re going to say, “Take them away.” We’ve done that with wheat and grain, and we can do it with other things if we put our minds to it.

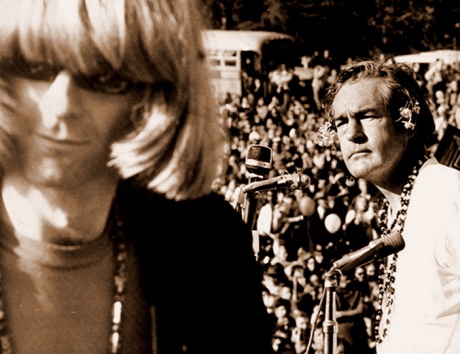

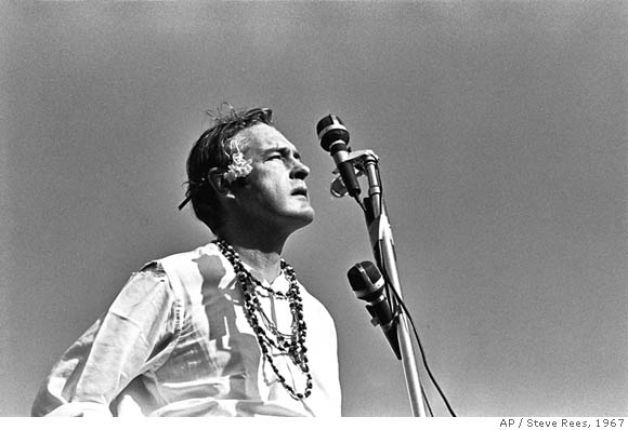

The way we define human beings will change. You won’t be a serf, a slave, or a worker. What will you be? A performer. Everyone will be performing. Passive listening, passive observing, passive watching will disappear. Of course, Big Brother, both of the Reagan and Ihe Gorbachev type, want us to be passive. They don’t want us to think for ourselves.

In 2007 you’ll be living in an information society in which information will be what money and machinery were in the Industrial Age. Everyone is going to be a psychologist, computer whiz, philosopher. Mind play, mind performance, psychological skill are going to be the equivalent of land, money, and power in the earlier ages.

Now to the nuts and bolts of this stuff: Every kid will learn how to communicate at a very young age; every kid will have his own computer — like a pair of sneakers, a pair of Nikes. No one will steal a computer, because you’ll throw them away. And everyone will learn how to chart his thoughts and his mental performance — like a baseball player’s stats. Even kids will plot their thoughts like they plot their batting average. The name of our species is Homo sapiens. That means we’re the organism that thinks, and our species finally will be proficient in thinking.

The biggest effect will be on blacks and members of other minority groups in this country. In the Information Age, to keep any poor kid from having a computer would be like keeping him from having food, medicine, shelter, or clothing now.

Within 20 years we’ll have scrapped the current system of partisan politics. Partisan politics belongs back in an age of feudalism, or at most the Industrial Age. It is insane to run a highly complicated, technological, pluralistic society like America when you have in the cabin of the spaceship a Democratic and a Republican candidate kneeing and gouging and beating up each other to see who’s going to be president for four years. In an electronic society an intelligent person would no more send Tip O’Neil to Washington to make his laws than you’d send Tip O’Neill to the wine shop to pick out a good wine for you.

Everyone is going to be responsible for government. It will be done by televoting, perhaps every Sunday between, say, twelve and one. But we’ll be voting on major issues — not parties, people, or a glamorous candidate who will play on our superstitions and emotions. You’ll educate yourself on the issues by using your own thought-processing appliances, the new computers. So you’ll be continually teaching yourself, continuously learning.

Right now there is a great deal of concern about the drug problem. In 20 years there will be hundreds of neurotransmitters that will allow you to boot up and activate your brain and change mental performance. There are going to be what I call brain radios — hearing aids you put in your ear— that will pick up and communicate with the electricity in your brain. You will be able to tune in any brain aspect, like sex, that you want. You will speed up or slow down your thinking. Anything you can do with chemicals you can do with brain waves, and they are so much healthier.

Drugs will be old-fashioned. No one will be addicted because you can just turn on the ultimate orgasm and keep it going for an hour. But how long are you going to do that? You’ll get bored. You’re going to want to turn it down or off. The criminality of drugs is what is causing the so-called drug crisis, but if you legalize a brain radio — and you’re going to have to — everyone will have the ability to dial into any emotional, mental, or sensual experience. We will use these radios to think more clearly and, above all, to communicate more clearly. The key to the twenty-first century will be five words: “think for yourself,” and “question authority.”

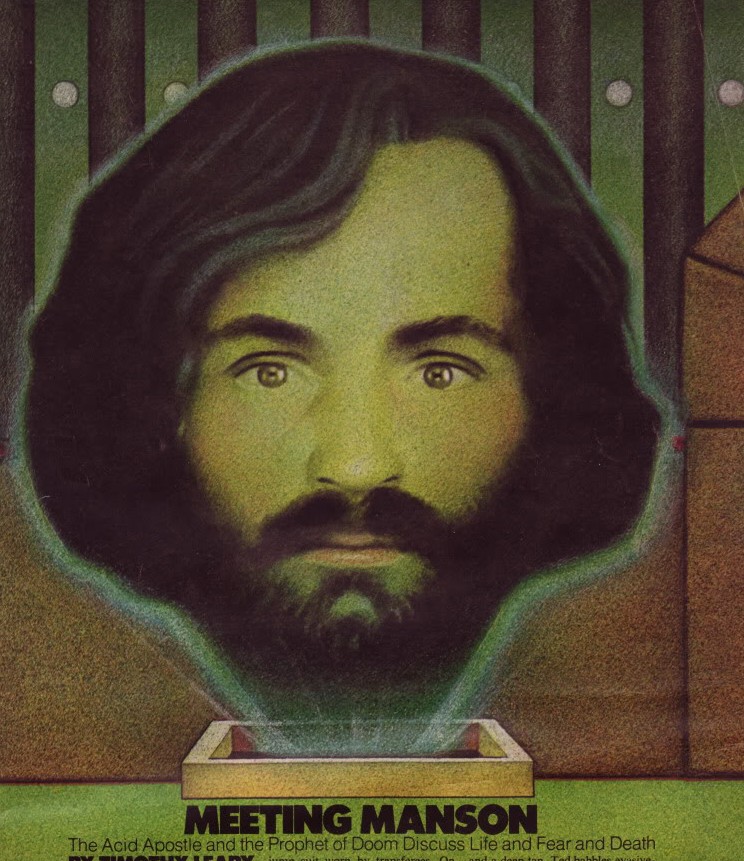

People will become more intelligent. I am really bored with the level of intelligence on this planet. There’s no one to talk to, and there is so much superstition. I am just waiting for people to smarten up. In 20 years I’ll have more fun, and I’ll have more people to talk to. People will be teaching me, and life is going to be more exciting. Twenty years ago — 1967 — the summer of love was just beginning, and I was busy performing the rituals that had to be performed then. The computers were IBM business machines that were used to de- personalize and control us. I frankly was too dumb to look ahead.•