Elon Musk has made the unilateral decision that Mars will be ruled by direct democracy, and considering how dismal his political record is over the last five months with his bewildering bromance with the orange supremacist, it might be great if he blasted from Earth sooner than later.

Another billionaire of dubious governmental wisdom also believed in direct democracy. That was computer-processing magnate Ross Perot who, in 1969, had a McLuhan-ish dream: an electronic town hall in which interactive television and computer punch cards would allow the masses, rather than elected officials, to decide key American policies. In 1992, he held fast to this goal–one that was perhaps more democratic than any society could survive–when he bankrolled his own populist third-party Presidential campaign.

The opening of “Perot’s Vision: Consensus By Computer,” a New York Times article from that year by the late Michael Kelly:

WASHINGTON, June 5— Twenty-three years ago, Ross Perot had a simple idea.

The nation was splintered by the great and painful issues of the day. There had been years of disorder and disunity, and lately, terrible riots in Los Angeles and other cities. People talked of an America in crisis. The Government seemed to many to be ineffectual and out of touch.

What this country needed, Mr. Perot thought, was a good, long talk with itself.

The information age was dawning, and Mr. Perot, then building what would become one of the world’s largest computer-processing companies, saw in its glow the answer to everything. One Hour, One Issue

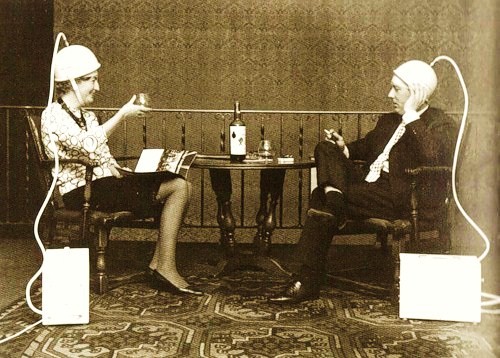

Every week, Mr. Perot proposed, the television networks would broadcast an hourlong program in which one issue would be discussed. Viewers would record their opinions by marking computer cards, which they would mail to regional tabulating centers. Consensus would be reached, and the leaders would know what the people wanted.

Mr. Perot gave his idea a name that draped the old dream of pure democracy with the glossy promise of technology: “the electronic town hall.”

Today, Mr. Perot’s idea, essentially unchanged from 1969, is at the core of his ‘We the People’ drive for the Presidency, and of his theory for governing.

It forms the basis of Mr. Perot’s pitch, in which he presents himself, not as a politician running for President, but as a patriot willing to be drafted ‘as a servant of the people’ to take on the ‘dirty, thankless’ job of rescuing America from “the Establishment,” and running it.

In set speeches and interviews, the Texas billionaire describes the electronic town hall as the principal tool of governance in a Perot Presidency, and he makes grand claims: “If we ever put the people back in charge of this country and make sure they understand the issues, you’ll see the White House and Congress, like a ballet, pirouetting around the stage getting it done in unison.”

Although Mr. Perot has repeatedly said he would not try to use the electronic town hall as a direct decision-making body, he has on other occasions suggested placing a startling degree of power in the hands of the television audience.

He has proposed at least twice — in an interview with David Frost broadcast on April 24 and in a March 18 speech at the National Press Club — passing a constitutional amendment that would strip Congress of its authority to levy taxes, and place that power directly in the hands of the people, in a debate and referendum orchestrated through an electronic town hall.•

In addition to the rampant myopia that would likely blight such a system, most Americans, with jobs and families and TV shows to binge watch, don’t take the time to fully appreciate the nuances of complex policy. The stunning truth is that even in a representative democracy in this information-rich age, we have enough uninformed voters minus critical-thinking abilities to install an obvious con artist into the Oval Office to pick their pockets.

In a Financial Times column, Tim Harford argues in favor of the professional if imperfect class of technocrats, who get the job done, more or less. An excerpt:

For all its merits, democracy has always had a weakness: on any detailed piece of policy, the typical voter — I include myself here — does not understand what is really at stake and does not care to find out. This is not a slight on voters. It is a recognition of our common sense. Why should we devote hours to studying every policy question that arises? We know the vote of any particular citizen is never decisive. It would be a deluded voter indeed who stayed up all night revising for an election, believing that her vote would be the one to make all the difference.

So voters are not paying close attention to the details. That might seem a fatal flaw in democracy but democracy has coped. The workaround for voter ignorance is to delegate the details to expert technocrats. Technocracy is unfashionable these days; that is a shame.

One advantage of a technocracy is that it constrains politicians who are tempted by narrow or fleeting advantages. Multilateral bodies such as the World Trade Organization and the European Commission have been able to head off popular yet self-harming behaviour, such as handing state protection to which ever business has the best lobbyists.

Meanwhile independent central banks have been the grown-ups of economic policymaking. Once the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis had passed, elected politicians sat on their hands. Technocratic central bankers were — to borrow a phrase from Mohamed El-Erian, economic adviser — “the only game in town” in sustaining a recovery.

A second advantage is that technocrats can offer informed, impartial analysis. Consider the Congressional Budget Office in the US, the Office for Budget Responsibility in the UK, and Nice, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Technocrats make mistakes, it’s true — many mistakes. Brain surgeons also make mistakes. That does not mean I’d be better off handing the scalpel to Boris Johnson.•