"Most people are fools, most authority is malignant, God does not exist, and everything is wrong." (Image by Tim Brailsford.)

To dream big is to risk failing big, and nobody in the computer world dreamed bigger than visionary Ted Nelson. The information pioneer and philosopher coined the term “hypertext” in 1963 and spent the majority of his life frustratingly, unsuccessfully working on Project Xanadu, a system that attempted to link networked computers with a simple interface decades before the invention of the World Wide Web. Nelson’s tilting at virtual windmills was the subject of a devastating Wired article in 1995 by Gary Wolf. An excerpt:

“Nelson’s life is so full of unfinished projects that it might fairly be said to be built from them, much as lace is built from holes or Philip Johnson’s glass house from windows. He has written an unfinished autobiography and produced an unfinished film. His houseboat in the San Francisco Bay is full of incomplete notes and unsigned letters. He founded a video-editing business, but has not yet seen it through to profitability. He has been at work on an overarching philosophy of everything called General Schematics, but the text remains in thousands of pieces, scattered on sheets of paper, file cards, and sticky notes.

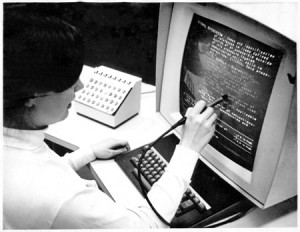

The Hypertext Editing System (HES), seen here being used at Brown University in 1969, was developed by Ted Nelson and others. (Image by Greg Lloyd.)

All the children of Nelson’s imagination do not have equal stature. Each is derived from the one, great, unfinished project for which he has finally achieved the fame he has pursued since his boyhood. During one of our many conversations, Nelson explained that he never succeeded as a filmmaker or businessman because ‘the first step to anything I ever wanted to do was Xanadu.’

Xanadu, a global hypertext publishing system, is the longest-running vaporware story in the history of the computer industry. It has been in development for more than 30 years. This long gestation period may not put it in the same category as the Great Wall of China, which was under construction for most of the 16th century and still failed to foil invaders, but, given the relative youth of commercial computing, Xanadu has set a record of futility that will be difficult for other companies to surpass. The fact that Nelson has had only since about 1960 to build his reputation as the king of unsuccessful software development makes Xanadu interesting for another reason: the project’s failure (or, viewed more optimistically, its long-delayed success) coincides almost exactly with the birth of hacker culture. Xanadu’s manic and highly publicized swerves from triumph to bankruptcy show a side of hackerdom that is as important, perhaps, as tales of billion-dollar companies born in garages.”