It’s perplexing that video games aren’t used to teach children history and science, though the economics aren’t easy. A blockbuster game on par with today’s best offerings can cost hundreds of millions to develop and design, and that’s a steep price without knowing if such software would be welcomed into classrooms.

In addition to cost, there’s always been a prejudice against learning devices because they seem to reduce students into just more machines. That’s not altogether false if you consider that B.F. Skinner saw pupils as “programmable.” In an Atlantic article by Jacek Krywko looks the latest attempts at the making of mind-improving machines, which will not only teach language but also “monitor things like joy, sadness, boredom, and confusion.” Such robot social intelligence is thought to be the key difference: Don’t try to make the students more like machines but the machines more like the students.

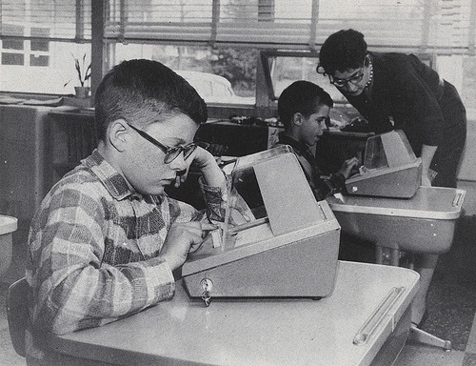

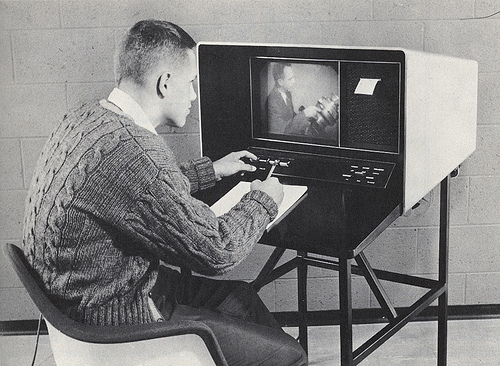

A passage about the Skinner’s failed attempts in the 1950s at making education more robotic:

His new device taught by showing students questions one at a time, with the idea that the user would be rewarded for each right answer.

This time, there was no “cultural inertia.” Teaching machines flooded the market, and backlash soon followed. Kurt Vonnegut called the machines “playthings” and argued that they couldn’t prepare a kid for “one-millionth of what is going to hit him in the teeth, ready or not.” Fortune ran a story headlined “Can People Be Taught Like Pigeons?” By the end of the ‘60s, teaching machines had once again fallen out of favor. The concept briefly resurfaced again in the ‘80s, but the lack of quality educational software—and the public’s perception of mechanized teachers as something vaguely Orwellian—meant they once again failed to gain much traction.

But now, they’re back for another try.

Scientists in Germany, Turkey, the Netherlands, and the U.K. are currently working on language-teaching machines more complex than anything [Sydney] Pressley or Skinner dreamed up.•