Steve Ditlea, who wrote the 1981 Inc report about Apple Computers banishing typewriters from its offices, published a piece in the same publication the following year about the birth of the software industry. One of the players he mentions was Gary Kildall, a star-crossed software pioneer who was elbowed aside by Microsoft and died young after some sort of mysterious injury suffered in a biker bar in Monterrey. An excerpt from Ditlea’s article, when Kildall and others were trying to code the future:

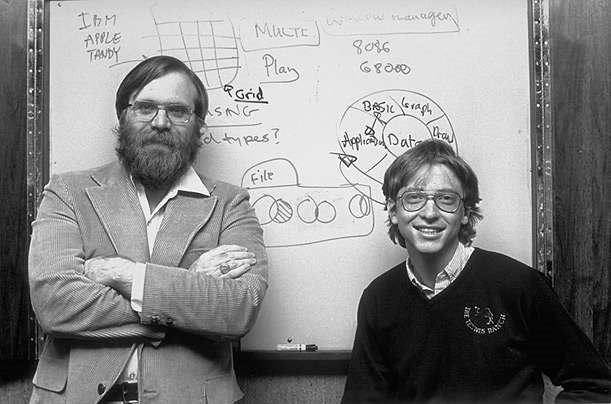

“In 1976, Bill Gates, then 20, and Paul Allen, 23, were running a company they had started the year before in Gates’s college dorm in Boston. That same year, Gary Kildall, 34 was starting a company in his backyard toolshed in California. Tony Gold, 30, was still a credit officer at a New York City bank. Dan Fylstra, 25, was starting at the Harvard Business School. Dan Bricklin, 25, was getting ready to apply to business schools in Massachusetts, and Bob Frankston, 27, was working as a computer programmer near Boston.

All seven of these people started and now run companies that produce and/or publish software for personal computers. All five of their companies — whose combined revenues just missed $50 million in 1981 — are doubling or tripling in size each year. All of these entrepreneurs are, or soon will be, millionaires. All are likely to be the leaders of the personal-computer software industry — quoted during economic crisis, looked up to by future business-school students.

The five companies they founded have created a new industry from scratch. And now they’ve been joined by as many as 1,000 more companies offering for sale some 5,000 software programs. The pressures to stay on top in the industry are intense. Some of the biggest companies in the country have turned their attention to micro software in recent months. Professional investors are scrambling to pour millions of dollars of venture capital into the leading companies. And the independents — only a dozen or so had sales of more than $1 million in 1981 — are straining to stay out in front.

‘It’s a tremendous business to be part of,’ says Mike Belling, 32, who bought the three-month-old Stoneware Inc. in June 1980 with his partner, Kenneth Klein, 42. ‘But it has its pitfalls, like cars used to. It’s all so brand new that there’s nothing to go by yet. There’s no history to tell you how many copies of a program to produce, for instance.’

Five years ago, the micro-software industry didn’t exist.”•