You can find in President Trump’s support the desire for an illusory America that will never be. The very complex problems which the candidate is ill-prepared to address have been dutifully avoided. There’s no discussion of automation vanishing jobs. There’s no talk about how China is the world leader in cancer rates and air pollution as partial payment for its hellbent shift into capitalism. You’ll hear from Trump that Dubai has such beautiful, modern airports and lavish golf courses because that state’s leaders are much smarter than ours are, but there’s no mention of their willingness to use quasi-slave labor.

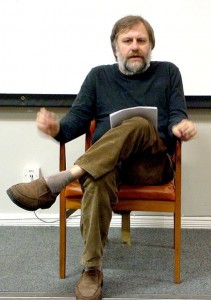

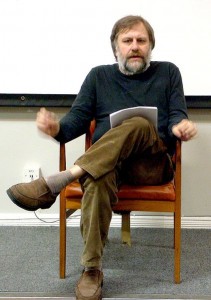

In a London Review of Books piece about the ongoing refugee crisis, Slavoj Žižek examines the need for a nouveau forms of slavery in the contemporary global economy. These people are still cheaper than machines, for now.

An excerpt:

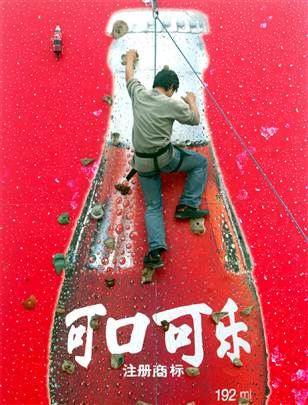

New forms of slavery are the hallmark of these wealthy countries: millions of immigrant workers on the Arabian peninsula are deprived of elementary civil rights and freedoms; in Asia, millions of workers live in sweatshops organised like concentration camps. But there are examples closer to home. On 1 December 2013 a Chinese-owned clothing factory in Prato, near Florence, burned down, killing seven workers trapped in an improvised cardboard dormitory. ‘No one can say they are surprised at this,’ Roberto Pistonina, a local trade unionist, remarked, ‘because everyone has known for years that, in the area between Florence and Prato, hundreds if not thousands of people are living and working in conditions of near slavery.’ There are more than four thousand Chinese-owned businesses in Prato, and thousands of Chinese immigrants are believed to be living in the city illegally, working as many as 16 hours a day for a network of workshops and wholesalers.

The new slavery is not confined to the suburbs of Shanghai, or Dubai, or Qatar. It is in our midst; we just don’t see it, or pretend not to see it. Sweated labour is a structural necessity of today’s global capitalism. Many of the refugees entering Europe will become part of its growing precarious workforce, in many cases at the expense of local workers, who react to the threat by joining the latest wave of anti-immigrant populism.

In escaping their war-torn homelands, the refugees are possessed by a dream. Refugees arriving in southern Italy do not want to stay there: many of them are trying to get to Scandinavia. The thousands of migrants in Calais are not satisfied with France: they are ready to risk their lives to enter the UK. Tens of thousands of refugees in Balkan countries are desperate to get to Germany. They assert their dreams as their unconditional right, and demand from the European authorities not only proper food and medical care but also transportation to the destination of their choice. There is something enigmatically utopian in this demand: as if it were the duty of Europe to realise their dreams – dreams which, incidentally, are out of reach of most Europeans (surely a good number of Southern and Eastern Europeans would prefer to live in Norway too?). It is precisely when people find themselves in poverty, distress and danger – when we’d expect them to settle for a minimum of safety and wellbeing – that their utopianism becomes most intransigent. But the hard truth to be faced by the refugees is that ‘there is no Norway,’ even in Norway.•