Is the human species more or less likely to become extinct since the development of civilization?

Not easy to answer. We didn’t have nukes to blow ourselves to bits when foragers, nor were there illnesses like smallpox pre-livestock. A disconnected slew of tribes also meant that disease was less likely to spread on a mass level. There are, of course, advantages to modern society beyond creature comforts and the ability to easily disseminate photographs of our genitals. Response to large-scale calamities are far better today, except in cases of willful neglect as with the performance of the racist game-show host in the White House in regards to Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Information-sharing on a global scale has proved to have its negatives, but it’s also made tracking disease and sharing genuine progress more possible. And the scientific tilt that made those nukes that can kill millions will also likely be able in time to safeguard us from natural “bombs” like meteorites and manipulate genes to eliminate illnesses. Of course, bioengineering will also be a bane. You get the point—things are better but they have the potential to be worse.

Of course, there are numerous considerations beyond existential threats. In Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, Yale anthropologist James Scott takes a revisionist look at why humans transitioned from foragers to farmers. He believes modern civilization did not have to be, life among the foragers was not as benighted as its made out to be, and that early farming life was terrible for humans. In a smart Vox Q&A conducted by Sean Illing, Scott also acknowledges that (most) people are better off now then they were then but only after a long, painful gestation period.

An excerpt about what may be humanity’s great inflection point:

Sean Illing:

You’re not arguing — and I’m certainly not arguing — that we would be better off if we all returned to this pre-modern world. No one wants to swap lives with someone from 10,000 years ago.

James Scott:

Of course. From our perspective today, it’s inconceivable that we would want to go back like that. But I think it’s still important to understand that this was not a choice between hunting and gathering and foraging on the one hand and the Danish welfare state on the other.

At this point in history, this was a choice between hunting and gathering and foraging on the one hand and an agrarian state in which all of the first epidemic diseases developed due to the concentration of animals and human beings in a concentrated space. This was not as clear-cut a choice as a lot of people suppose.

Yes, things are better now, but it’s really only in the last 200 years or so that we’ve enjoyed the health and longevity that we do today. But this initial period when we think civilization was created was, in fact, a really dark period for humanity.

Sean Illing:

What have the demands of modern civilization done to the individual? We enjoy more abundance and greater comfort, but at the same time many of us are less happy, less free, and more cut off from our natural environment. Isn’t this the real price of civilization?

James Scott:

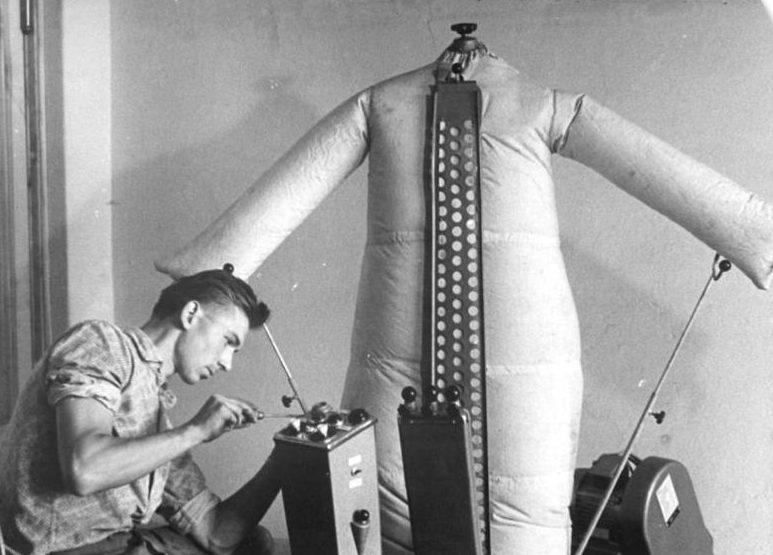

It’s an important question. Modern industrial life has forced almost all of us to specialize in something, often in mundane, repetitive tasks. This is good for economic productivity but not so good for individual self-fulfillment. I think this has created a narrowing of attention to the larger world. Moving from hunting and gathering to working on an assembly line has made us more machine-like and less attuned to the world around us because we only have to be skilled at one thing.

Sean Illing:

I want to press you a bit on this question of whether we’re any happier now. We live mostly isolated lives in a culture that prizes growth over sustainability. We’re encouraged to own more things, to buy more things, to define and measure ourselves against others on the basis of status and wealth. I think this has made us less happy and more self-conscious. How do you see it?

James Scott:

I’d say two things. The first is that once we had sedentary agriculture, we then had investment in land and therefore property that could be taxed. We then had the basis for inherited property and thus the basis for passing wealth from one generation to another.

Now, all that matters because it led to these embedded inequalities that were enforced by the state protection of property. This wasn’t true for hunter and gatherer societies, which regarded all property as common property to which everyone in the tribe had equal access. So the early agricultural societies created the basis for systematic class distinctions that could be perpetuated between generations, and that’s how you get the kinds of massive hierarchies and inequalities we see today.•