Fascists use shocking words and actions to see how far they can move the line. Mock POWs and the disabled, say you can shoot someone and your poll numbers wouldn’t dip, exclaim that the NRA “could deal with” your political opponent, and if enough people are accepting of your indecency and not enough push back, you know you can go even a little farther the next time. Autocrats also try to erase the line between facts and lies, so that nothing seems certain. Truth, that slippery thing that must be pursued for the sake of a civil society, was a casualty of Donald Trump’s odious, nihilistic, fake-news campaign. These tactics have only continued in the post-election period.

In his inaugural speech, Trump referred to “American carnage,” a ridiculous overstatement. It was a purposeful remark he hopes will later allow him license to commit extreme acts far beyond the norm. On Saturday in a pseudo-presser, Sean Spicer knowingly read lies about the inaugural crowd size, allowing no one to question his illegitimate remarks. The following day, Kellyanne Conway described these very lies as “alternative facts,” aiming to make reality and fantasy appear equally true. It’s clear that an attack on veracity, on consensus, will be a hallmark of this Administration. Because when nothing is sure, everything is possible, even “unspeakable things.”

That’s why, despite what Wall Street Journal Editor-in-Chief Gerald Baker thinks, every lie must be called just that, each untruth must receive response, every outrage must be censured. If not, the line will move further, until there’s nowhere safe left to stand.

From “Donald Trump’s Authoritarian Politics of Memory,” by Ruth Ben-Ghiat of the Atlantic:

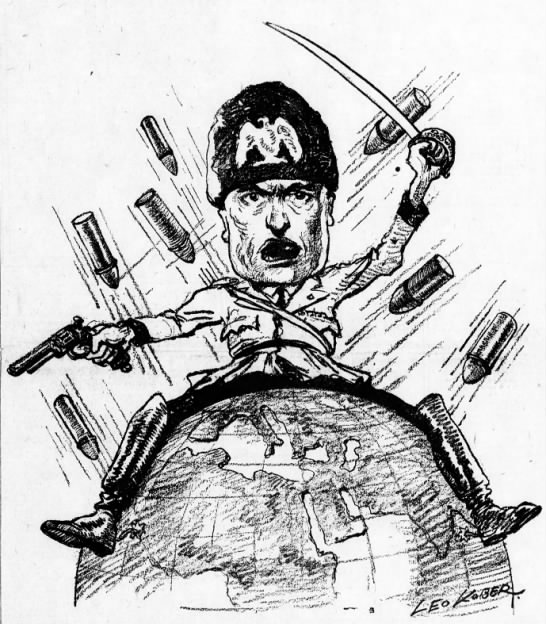

President Donald Trump’s journey to the pinnacle of American power has offered the opportunity to study these processes in real time. Although we cannot yet know what kind of president he will be, from his June 2015 declaration of candidacy to his January 2017 inauguration, Trump has undertaken two parallel projects aimed at unsettling the mental habits and moral foundations of American democracy. First, he has cultivated a political persona that inspires adulation and unquestioning loyalty that can be mobilized for action on his behalf. Second, he has initiated Americans into a culture of threat that not only desensitizes them to the effects of bigotry but also raises the possibility of violence without consequence.

The founding moment of this era came one year ago, when Trump declared at a rally, “I could stand on Fifth Avenue and shoot someone and not lose any voters.” Trump signaled that rhetorical and actual violence might have a different place in America of the future, perhaps becoming something ordinary or unmemorable. During 2016, public hatred became part of everyday reality for many Americans: those who identify with the white supremacist alt-right like Richard Spencer openly hold rallies; elected officials feel emboldened to call for political opponents to be shot (as did New Hampshire and Oklahoma State Representatives Al Baldasaro and John Bennett, among others); journalists reporting on Trump and hijab-wearing women seek protection protocols and escorts. The bureaucratic-sounding term many use for this, “normalization,” does not fully render the operations of memory that make it possible. Driven by opportunism, pragmatism, or fear, many begin to forget that they used to think certain things were unacceptable.

The risk is that the parameters of thought and action will be nudged to align with those of the leader, easing the retrofitting of history to suit his personalization of the land’s highest office. Trump’s success at this in a country known for individualism, and with no history of living under an authoritarian ruler, shows how susceptible people are to such approaches.Trump’s bullying charm anchors this culture of threat.•