When embattled chess champion Bobby Fischer wasn’t searching for God and girls, he was living an odd and paranoid existence. In William Knack’s fascinating and fairly crazy 1985 Sports Illustrated article, the reporter relays how Fischer once reluctantly passed on a 1979 meeting with Wilt Chamberlain at the basketball star’s mansion and also reneged on a deal the same year to play an exhibition match at Caesars Palace for $250,000. Oh, and Knack also disguises himself as a bum and stalks Fischer (with some success) at the Los Angeles Public Library. It’s probably the best and most apropos thing I’ve read about the chess champion’s break from public life–and reality. An excerpt:

Moments later I was heading for the library in Los Angeles. Time was getting short. By now, the office was restless, and more than one editor had told me to write the story whether I had found him or not, but I was having trouble letting it go.

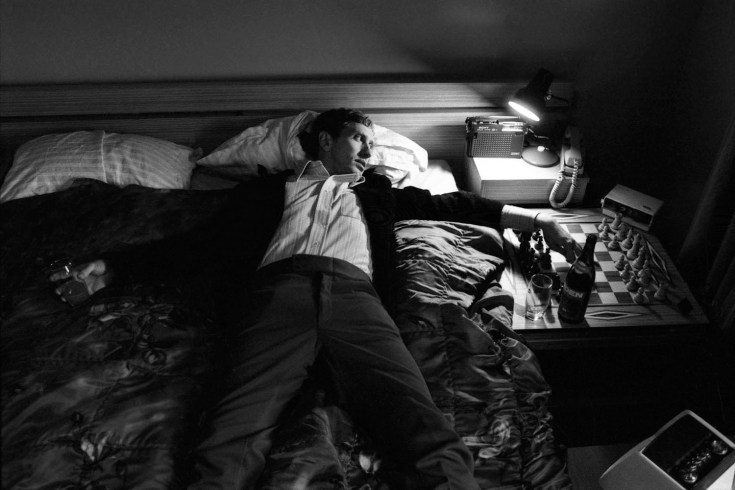

So what was I doing here, dressed up like an abject bum and looking for a rnan who would bolt the instant he knew who I was? And what on earth might he be doing now in the desert? Pumping gas in Reno? Riding a burro from dune to dune in the Mojave, looking over his shoulder as the sun boiled the brain that once ate Moscow? And what of his teeth? I had been thinking a lot lately about Fischer’s teeth. In the spring of 1982, one of Fischer’s oldest chess-playing friends, Ron Gross of Cerritos, Calif., suggested to him that the two men take a fishing trip into Mexico. Gross, now 49, had first met Fischer in the mid-’50s, back in the days before Bobby had become a world-class player, and the two had kept in irregular touch over the years. In 1980, at a time when Fischer was leaving most of his old friends behind, he had contacted Gross, and they had gotten together. At the time, Fischer was living in a dive near downtown Los Angeles.

“It was a real seedy hotel,” Gross recalls. “Broken bottles. Weird people.”

At one point, Gross made the mistake of calling Karpov the world champion. “I’m still the world champion,” snapped Fischer. “Karpov isn’t. My friends still consider me champion. They took my title from me.”

By 1982, Fischer was living in a nicer neighborhood in Los Angeles. Gross began picking him up and letting him off at a bus stop at Wilshire Boulevard and Fairfax, near an East Indian store where Bobby bought herbal medicines.

That March, on the fishing trip to Ensenada, Fischer got seasick, and he treated himself by sniffing a eucalyptus-based medicine below deck. Fischer astonished Gross with the news about his teeth. Fischer talked about a friend who had a steel plate in his head that picked up radio signals.

“If somebody took a filling out and put in an electronic device, he could influence your thinking,” Fischer said. “I don’t want anything artificial in my head.”

“Does that include dental work?” asked Gross.

“Yeah,” said Bobby. “I had all my fillings taken out some time ago.”

“There’s nothing in your cavities to protect your teeth?”

“No, nothing.”

Gross dropped the subject for the moment, but later he got to thinking about it and, while taking a steam bath in a health spa in Cerritos, he asked Fischer if he knew how bacteria worked, warning him that his teeth could rot away. “As much as you like to eat, what are you going to do when your teeth fall out?” asked Gross.

“I’ll gum it if I have to,” Fischer said. “I’ll gum it.”•