IEEE Spectrum has an interesting article in which a raft of scientists and futurists are questioned about the ETA of conscious machines and their potential impact. Notably, nobody says such a development is impossible nor does anyone suggest pursuit of such has a good chance to extinct us.

Robin Hanson, author The Age of Em, sticks to his previous prognostication that our increasingly technological future may bring us an economy that doubles every month, which might seem inviting to a society in stagnation, but a world that could potentially “turn over” so quickly would be a shock to the system to anyone not gradually eased into it.

Marthine Rothblatt, the Sirius founder turned Transhumanist and developer of “consciousness software,” believes robots will largely be “good,” saying that she’s “confident the computers will be overwhelmingly friendly since they will be selected for in a Darwinian environment that consists of humanity. There is no market for [a] bad robot, no more than there is for a bad car or plane. Of course, there is the inevitability of a DIY bad human-level computer, but that gives me even more reason to welcome human-level cyberintelligence, because just like it takes a [thief to catch a thief], it will take a human-friendly smart computer to catch an antihuman smart computer.”

There’s also no market for terrorism or for genocide, but those things happen. We can’t avoid far stronger tools because of the human capacity to cause chaos, but we have to at least consider the possibility that our own doom is embedded in these advances.

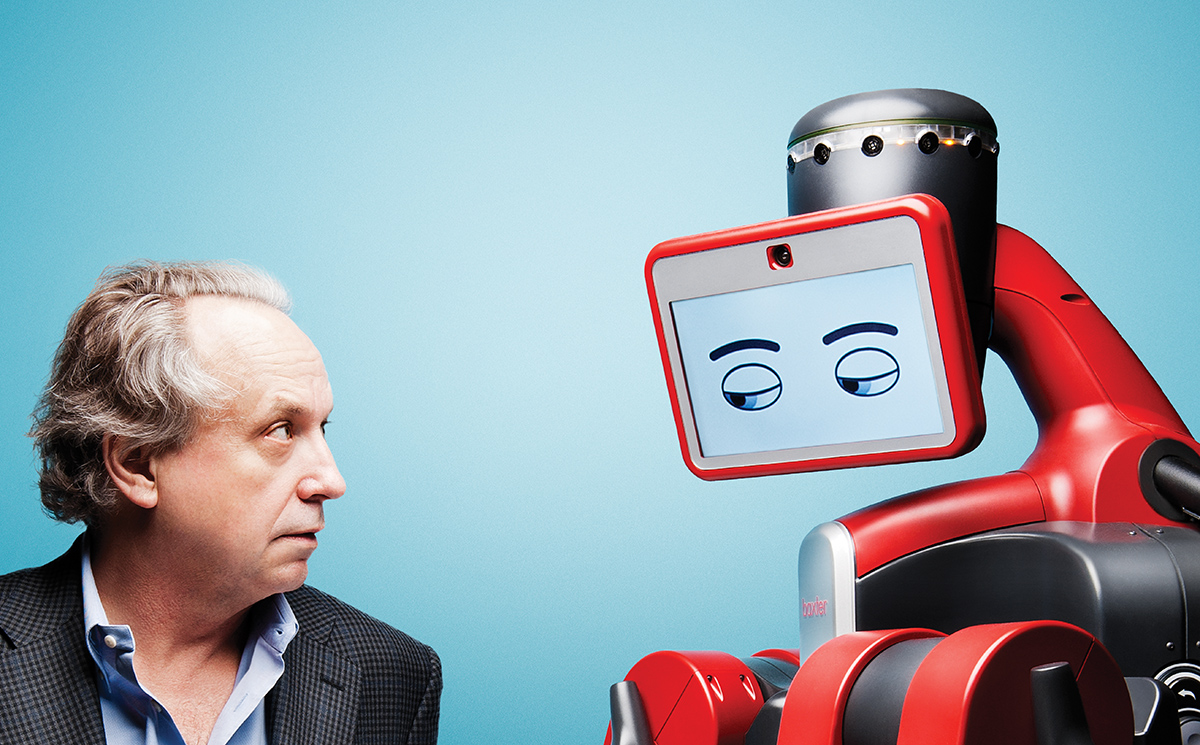

Rodney Brooks is perhaps the most sober of all the participants. In Errol Morris’ 1997 documentary, Fast, Cheap and Out of Control, the roboticist famously says that in tomorrow’s world of intelligent machines, humans might not be necessary. Brooks, who has since backed off that statement (“You can’t expect me to stand by something I said during a long day of filming 20 years ago!”), now mocks what he believes to be reckless conjecture about the future.

An excerpt:

Question:

When will we have computers as capable as the brain?

Rodney Brooks:

Rodney Brooks’s revised question: When will we have computers/robots recognizably as intelligent and as conscious as humans?

Not in our lifetimes, not even in Ray Kurzweil’s lifetime, and despite his fervent wishes, just like the rest of us, he will die within just a few decades. It will be well over 100 years before we see this level in our machines. Maybe many hundred years.

Question:

As intelligent and as conscious as dogs?

Rodney Brooks:

Maybe in 50 to 100 years. But they won’t have noses anywhere near as good as the real thing. They will be olfactorily challenged dogs.

Question:

How will brainlike computers change the world?

Rodney Brooks:

Since we won’t have intelligent computers like humans for well over 100 years, we cannot make any sensible projections about how they will change the world, as we don’t understand what the world will be like at all in 100 years. (For example, imagine reading Turing’s paper on computable numbers in 1936 and trying to project out how computers would change the world in just 70 or 80 years.) So an equivalent well-grounded question would have to be something simpler, like “How will computers/robots continue to change the world?” Answer: Within 20 years most baby boomers are going to have robotic devices in their homes, helping them maintain their independence as they age in place. This will include Ray Kurzweil, who will still not be immortal.

Question:

Do you have any qualms about a future in which computers have human-level (or greater) intelligence?

Rodney Brooks:

No qualms at all, as the world will have evolved so much in the next 100+ years that we cannot possibly imagine what it will be like, so there is no point in qualming. Qualming in the face of zero facts or understanding is a fun parlor game but generally not useful. And yes, this includes Nick Bostrom.•