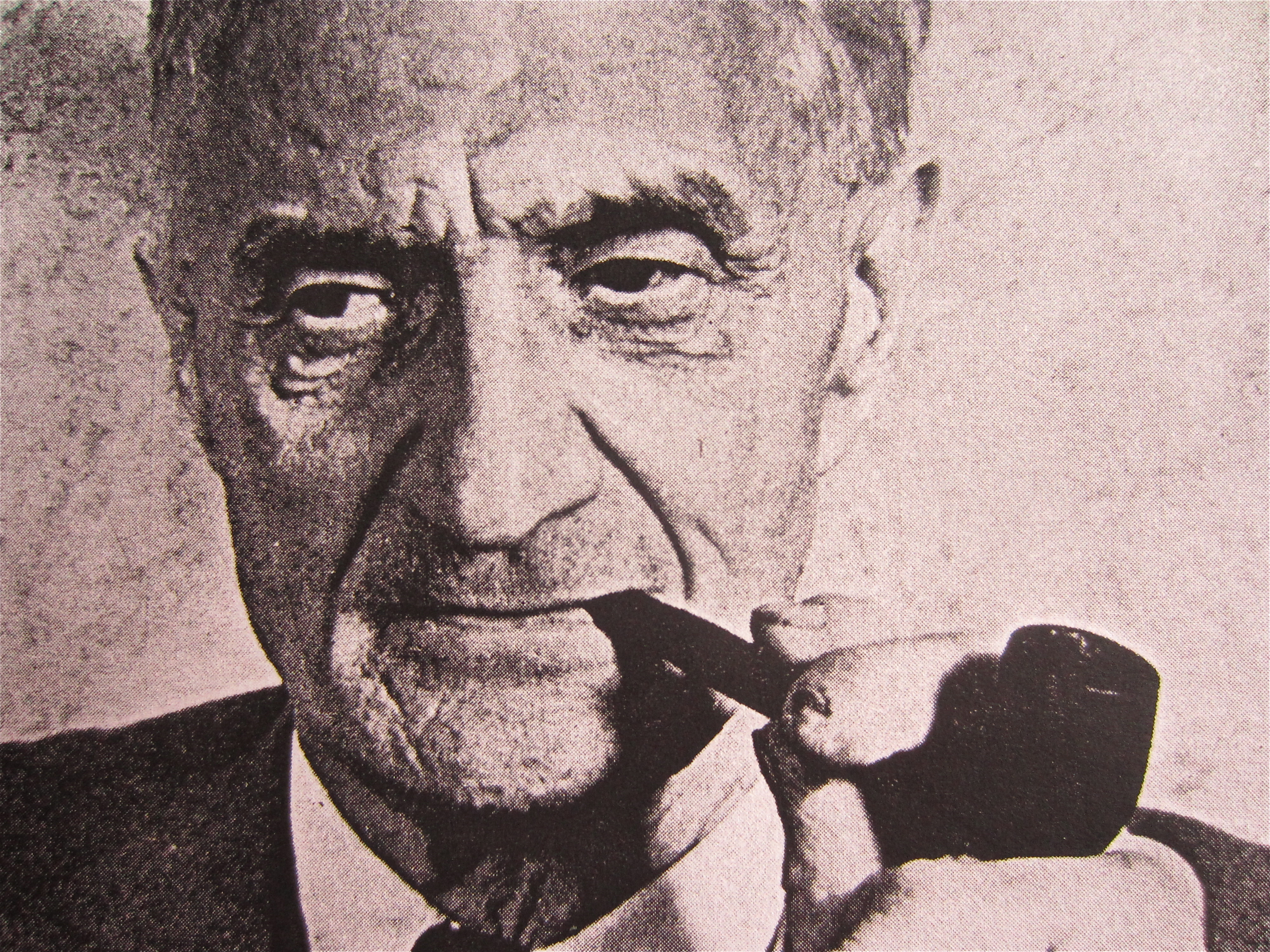

Bruno Hauptmann’s executioner, Robert G. Elliott, became increasingly anxious as the fateful hour neared, and you could hardly blame him. Who knows what actually happened to the Lindbergh baby, but the circumstances were crazy, with actual evidence intermingling with that appeared to be the doctored kind. To this day, historians and scholars still argue the merits of Hauptmann’s conviction. Elliot who’d also executed Sacco & Vanzetti and Ruth Snyder, was no stranger to high-profile cases, but the Lindbergh case may still be the most sensational in American history, more than Stanford White’s murder or O.J. Simpson’s race-infused trial.

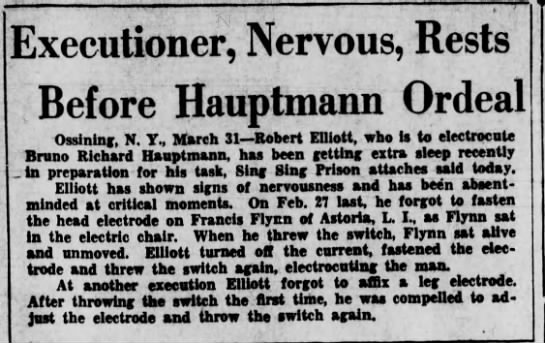

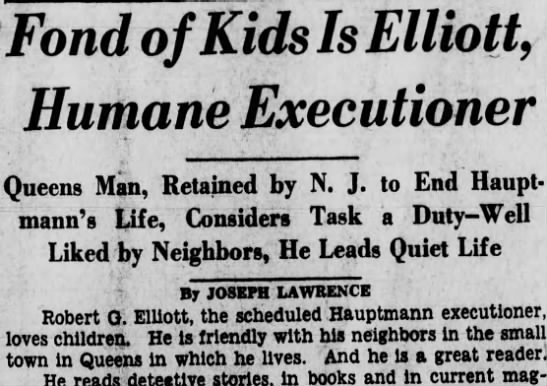

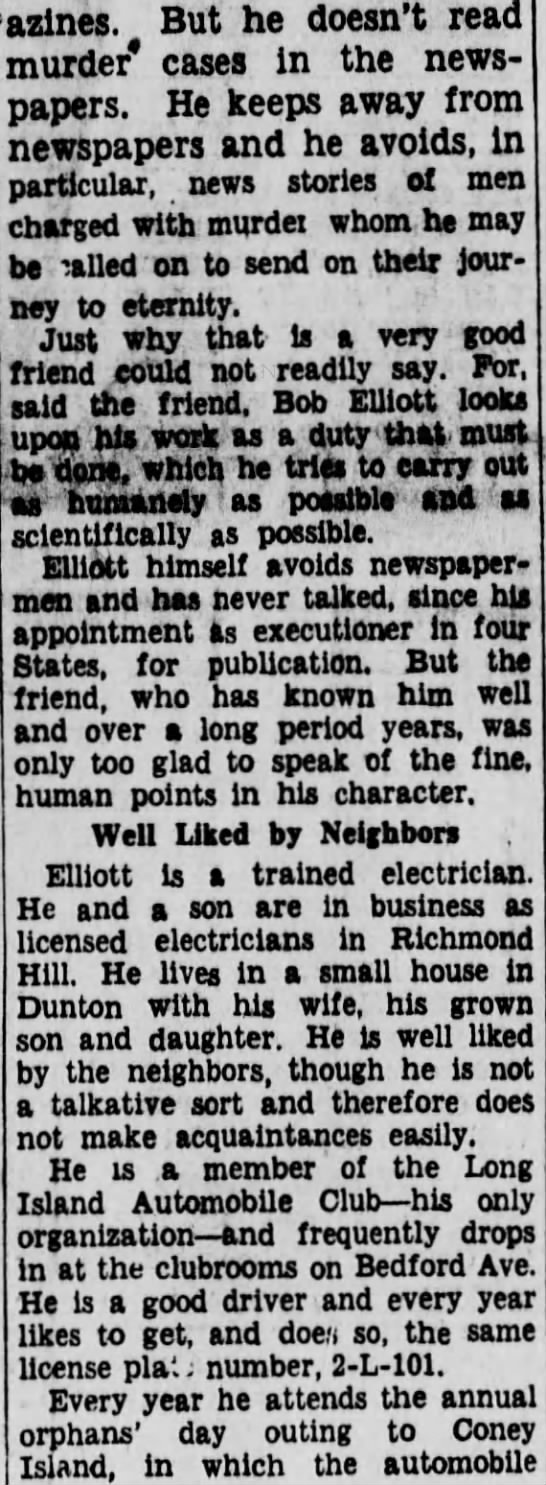

Elliott, whose title was the relatively benign “State Electrician” of New York had succeeded in the position John W. Hulbert, who was so troubled by his job and fears of retaliation, he committed suicide. Elliott, who came to be known as the “humane executioner” for devising a system that minimized pain, was said to be a pillar of the community who loved children and reading detective stories. A friend of his explained the Elliott’s general philosophy regarding the lethal work in a March 31, 1936 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article, just days before Hauptmann’s demise: “It is repulsive to him to have to execute a woman, but he feels that, after all, he’s just a machine.” Such rationalizations were necessary since Elliott claimed to be fiercely opposed to capital punishment, believing the killings accomplished nothing.