Richard Brautigan, who died in 1984 despite being all watched over by machines of loving grace, in interviewed a year before his passing on German TV.

You are currently browsing articles tagged Richard Brautigan.

Tags: Richard Brautigan

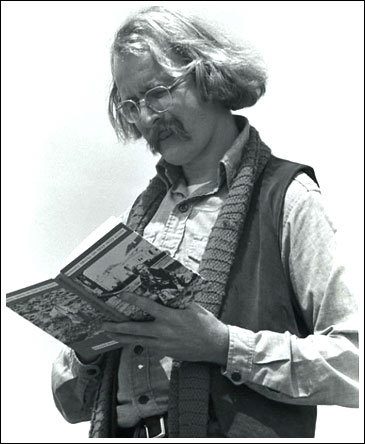

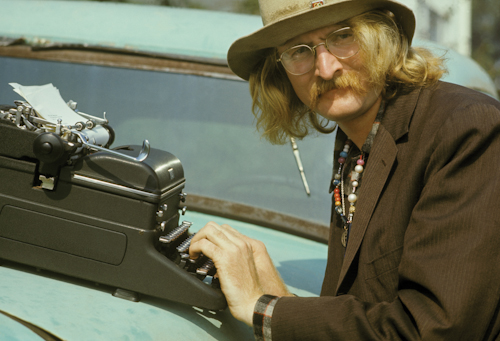

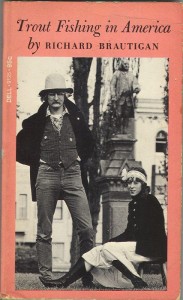

A miscast spokesperson of drugged-out hippies, the writer Richard Brautigan wasn’t enamored with narcotics nor the wide-eyed, bell-bottomed set. He wrote two things I love: The 1967 novel Trout Fishing in America and the 1968 poem “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace.” The opening of “King of the Granola Heads” Michael LaPointe’s Times Literary Supplement review of a new book about the iconoclastic author:

“Richard Brautigan, the Love Generation’s prickly and whimsical poet-novelist, died what the sheriff’s report termed an ‘unattended death’ on September 16, 1984. Having committed suicide with one of his beloved Smith & Wesson revolvers, Brautigan was not discovered in his home in Bolinas, California until October 25, at which point he needed to be ‘scooped up with a shovel.’ Why did Brautigan, the author of bestselling, generation-defining novels such as Trout Fishing in America and In Watermelon Sugar, die so alone? In Jubilee Hitchhiker, William Hjortsberg maps the rocketing rise and disastrous decline of this most quixotic American author.

Born in 1935 to a single mother in Tacoma, Washington, Richard Gary Brautigan was destined for a life on the fringes. He was even, at first, estranged from his own name, his mother borrowing the surname Porterfield from one of his many stepfathers. Unmoored from ancestry, Brautigan would always be a self-mythologizer, complicating the biographer’s task, but in the early, ‘Dick Porterfield’ chapters of Jubilee Hitchhiker, Hjortsberg disentangles events from their embellishments. ‘Imagination feeds on the irrational,’ he writes, and Brautigan’s young mind was given a steady diet. The midcentury Pacific Northwest has the larger-than-life dimensions of legend, complete with a near-apocalyptic flood, which the Porterfield family was the last to escape, ‘watching the highway fold up behind them ‘like scrambled eggs.’

After the deluge, Brautigan acquired his major trope: ‘Fishing consumed [his] life.’ With his towering height, white-blond, soup bowl haircut and overalls, the young Brautigan resembled Tom Sawyer, ‘hitchhiking up the McKenzie in the rain with a fly rod under his arm and a peanut butter sandwich in his pocket.’ Brautigan would always retain an anachronistic quality. By the age of twelve, he was collecting cans, blackberries and nightcrawlers to help the family make ends meet. In 1956, he hitchhiked down to San Francisco and never saw or spoke to his family again.” (Thanks Browser.)

See also:

From Lawrence Wright’s 1985 Rolling Stone article about the death of writer Richard Brautigan:

“The old Beats looked at Richard with envy and surprise. The Beats were out of fashion, and Bunthorne was all the rage and he was rich, too, thunderously rich by their standards. Ferlinghetti had been the first to publish parts of Trout Fishing in his City Lights Journal, but like most Beats, he had never taken Richard’s writing seriously. ‘As an editor, I always kept waiting for Richard to grow up as a writer,’ he says now. ‘I never could stand cute writing. He could never be an important writer like Hemingway — with that childish voice of his. Essentially he had a naïf style, a style based on a childlike perception of the world. The hippie cult was itself a childlike movement. I guess Richard was all the novelist the hippies needed. It was a nonliterate age.’

But it was an extraordinary time in every other respect. Cultural forms were exploding in the face of furious experimentation with drugs, art, sex, music, religion, social roles. Richard’s attitude toward all this, however, was ambivalent. He was widely credited with being the voice of the Summer of Love, but in fact he was contemptuous of most hippies, whom he saw as freeloaders and dizzy peaceniks. He had a horror of narcotics that seemed fanciful to his friends everybody used dope in those days except Richard.

His passions were basketball, the Civil War, Frank Lloyd Wright, Southern women writers, soap operas, the National Enquirer, chicken-fried steak and talking on the telephone. Wherever he was in the world, he would phone up his friends and talk for hours, sometimes reading them an entire book manuscript on a transpacific call. Time meant nothing to him, for he was a hopeless insomniac. Most of his friends dreaded it when Richard started reading his latest work to them, because he could not abide criticism of any sort. He had a dead ear for music. Ianthe remembered that he used to buy record albums because of the girls on the covers. He loved to take walks, but he loathed exercise in any other form.”

Another Richard Brautigan post:

Tags: Lawrence Wright, Richard Brautigan

Adam Curtis’ silicon-phobic BBC documentary series, which takes its title from Richard Brautigan’s great poem.

Tags: Adam Curtis, Richard Brautigan

“All Watched Over

by Machines of Loving Grace”

by Richard Brautigan, 1968.

I’d like to think (and

the sooner the better!)

of a cybernetic meadow

where mammals and computers

live together in mutually

programming harmony

like pure water

touching clear sky.

I like to think

(right now, please!)

of a cybernetic forest

filled with pines and electronics

where deer stroll peacefully

past computers

as if they were flowers

with spinning blossoms.

I like to think

(it has to be!)

of a cybernetic ecology

where we are free of our labors

and joined back to nature,

returned to our mammal brothers and sisters,

and all watched over

by machines of loving grace.

Tags: Richard Brautigan