“You are what the scoreboard says you are,” pronounced Bill Parcells in a moment of Zen neatness, but it isn’t always so. In the case of the perfectly named Washington Generals basketball coach Red Klotz, losing was winning, serving as he did as the leader of the long-running, sad-sack opposition to the Harlem Globetrotters. In an excellent edition of “The Lives They Lived” in the New York Times Magazine, Sam Dolnick pays tribute to the late coach’s lonely victory. An excerpt:

“He was a 5-foot-7 dynamo with a sly grin and a textbook set shot. In his prime, he was one of the best shooters in the country and a member of the championship-winning Baltimore Bullets in the late ’40s.

But Red Klotz made losing his life’s work.

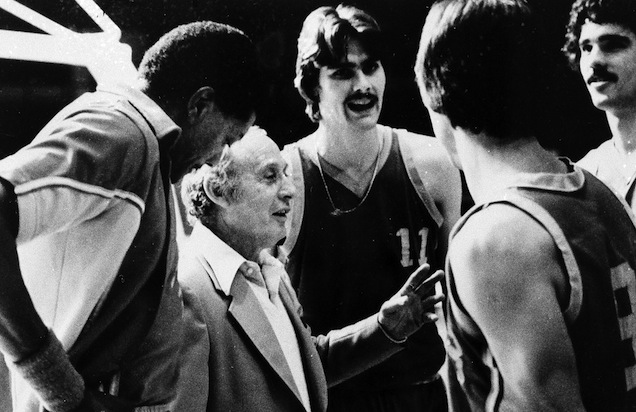

He was the owner, manager, coach, mascot and chauffeur (in a used green DeSoto) of the Washington Generals, a team he created to lose, night in and night out, to the Harlem Globetrotters. He also cast himself as the Generals’ star point guard, a snowy-haired old man in kneepads still sinking set shots well into his 60s.

The Generals would become the sorriest team in the history of sports — 14,000 losses and counting — but from the beginning theirs was a single-minded, almost existential mission, as ineluctable as mortality. To be born is to die; to be a General is to lose. Over the years, Klotz’s Generals lost in the Egyptian desert and on N.B.A. floors, at Disney World and the Attica Correctional Facility, in a Simpsons episode and in Hong Kong. They lost in front of Nikita Khrushchev and Barack Obama.

They should have lost on Jan. 5, 1971, too, inside a rickety gym in Martin, Tenn. They limped into town with a losing streak at 2,495 games. No one expected the night to end in any other way than with loss No. 2,496.

But the Globetrotters were off their game. Meadowlark Lemon, one of the team’s stars, couldn’t make a shot. The Generals, meanwhile, a collection of former collegians playing as the New Jersey Reds that night — one of several phony names used to give the impression that multiple hapless teams chased the Globetrotters around the court (and the country) — couldn’t miss.

The Generals were up 12 with just two minutes to go.

With seven seconds left, the universe regained its balance: Lemon scored to give the Globetrotters a 99-98 lead. Then Klotz answered from some 20 feet out: 100-99, Generals.

All part of the show . . . right? Surely the Generals knew the script: Let the Globetrotters make a last-second basket to win the game.

On cue, Lemon shot. Lemon missed. The game was over. The Generals — the Generals! — had won.

The sold-out crowd sat silent, stunned. For a brief moment in a small town in northern Tennessee, to be born was not to die. Then the booing began. People had not paid to see the Globetrotters lose.

In his book on the Globetrotters, Ben Green called the game a blow to American confidence, putting it alongside Lt. William Calley’s conviction in the My Lai massacre and the publication of the Pentagon Papers.”