“Carver’s prose does not flinch,” Giles Harvey wrote in a 2010 NYRB piece of the short stories of the late deadpan tragedian Raymond Carver, which were marked by sinewy sentences that spoke truths which could not be altered nor were they protested.

For decades there’s been a controversy over the role of Carver’s editor Gordon Lish in perfecting the lean stories, which were pruned and reshaped significantly from manuscript to publication. It’s a contretemps that survived Carver, who died at 50 in 1988, and one that continues to irk his widow, Tess Gallagher, though it does seem Lish’s participation was more meaningful than the average. And it also feels like stories were sometimes cut too much, that fragments of bone had been removed along with the fat.

More from Harvey’s piece, a passage about Carver receiving the edited copy of What We Talk About When Talk About Love:

He had just spent the whole night going over Lish’s edited version of the book and was taken aback by the changes. His manuscript had been radically transformed. Lish had cut the total length of the book by over 50 percent; three stories were at least 70 percent shorter; ten stories had new titles and the endings of fourteen had been rewritten.•

Of course, we don’t let the questions of Shakespeare’s authorship ruin that canon, so eventually this literary feud will matter little, just the work will remain. But you can understand how it peeves the surviving principals.

The opening of D.T. Max’s 1998 New York Times Magazine piece, “The Carver Chronicles“:

For much of the past 20 years, Gordon Lish, an editor at Esquire and then at Alfred A. Knopf who is now retired, has been quietly telling friends that he played a crucial role in the creation of the early short stories of Raymond Carver. The details varied from telling to telling, but the basic idea was that he had changed some of the stories so much that they were more his than Carver’s. No one quite knew what to make of his statements. Carver, who died 10 years ago this month, never responded in public to them. Basically it was Lish’s word against common sense. Lish had written fiction, too: If he was such a great talent, why did so few people care about his own work? As the years passed, Lish became reluctant to discuss the subject. Maybe he was choosing silence over people’s doubt. Maybe he had rethought what his contribution had been — or simply moved on.

Seven years ago, Lish arranged for the sale of his papers to the Lilly Library at Indiana University. Since then, only a few Carver scholars have examined the Lish manuscripts thoroughly. When one tried to publish his conclusions, Carver’s widow and literary executor, the poet Tess Gallagher, effectively blocked him with copyright cautions and pressure. I’d heard about this scholar’s work (and its failure to be published) through a friend. So I decided to visit the archive myself.

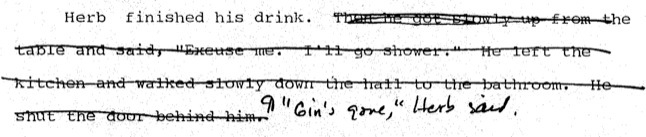

What I found there, when I began looking at the manuscripts of stories like ”Fat” and ”Tell the Women We’re Going,” were pages full of editorial marks — strikeouts, additions and marginal comments in Lish’s sprawling handwriting. It looked as if a temperamental 7-year-old had somehow got hold of the stories. As I was reading, one of the archivists came over. I thought she was going to reprimand me for some violation of the library rules. But that wasn’t why she was there. She wanted to talk about Carver. ”I started reading the folders,” she said, ”but then I stopped when I saw what was in there.”

It’s understandable that Lish’s assertions have never been taken seriously. The eccentric editor is up against an American icon. When he died at age 50 from lung cancer, Carver was considered by many to be America’s most important short-story writer. His stories were beautiful and moving. At a New York City memorial service, Robert Gottlieb, then the editor of The New Yorker, said succinctly, ”America has just lost the writer it could least afford to lose.” Carver is no longer a writer of the moment, the way David Foster Wallace is today, but many of his stories — ”Cathedral,” ”Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?” and ”Errand” — are firmly established in the literary canon. A vanguard figure in the 1980’s, Carver has become establishment fiction.

That doesn’t capture his claim on us, though. It goes deeper than his work. Born in the rural Northwest, Carver was the child of an alcoholic sawmill worker and a waitress. He first learned to write through a correspondence course. He lived in poverty and suffered multiple bouts of alcoholism throughout his 30’s. He struggled in a difficult marriage with his high-school girlfriend, Maryann Burk. Through it all he remained a generous, determined man — fiction’s comeback kid. By 1980, he had quit drinking and moved in with Tess Gallagher, with whom he spent the rest of his life. ”I know better than anyone a fellow is never out of the woods,” he wrote to Lish in one of dozens of letters archived at the Lilly. ”But right now it’s aces, and I’m enjoying it.” Carver’s life and work inspired faith, not skepticism.

Still, a quick look through Carver’s books would suggest that what Lish claims might have some merit.•