Lenny Bruce understood that there were few things more obscene than a society full of people making believe that obscene things never happened, since pretending and suppressing and hiding and shushing allows true evil to flourish. The opening of Ralph J. Gleason’s emotional 1966 obituary of Bruce in Ramparts:

“WHEN THE BODY OF LEONARD SCHNEIDER—stage name Lenny Bruce—was found on the floor of his Hollywood hills home on August 3, the Los Angeles police immediately announced that the victim had died of an overdose of a narcotic, probably heroin.

The press and TV and radio of the nation—the mass media—immediately seized upon this statement and headlined it from coast to coast, never questioning the miracle of instant diagnosis by a layman.

The medical report the next day, however, admitted that the cause of death was unknown and the analysis ‘inconclusive.’ But, as is the way with the mass media, news grows old, and the truth never quite catches up. Lenny Bruce didn’t die of an overdose of heroin. God alone knows what he did die of.

It is ritualistically fitting that he should be the victim, in the end, of distorted news, police malignment and the final irony—being buried with an orthodox Hebrew service, after years of satirizing organized religion. But first, in a sinister evocation of Orwell and Kafka and Greek tragedy, he had to be tortured, the record twisted, and the files rewritten until his death became a relief.

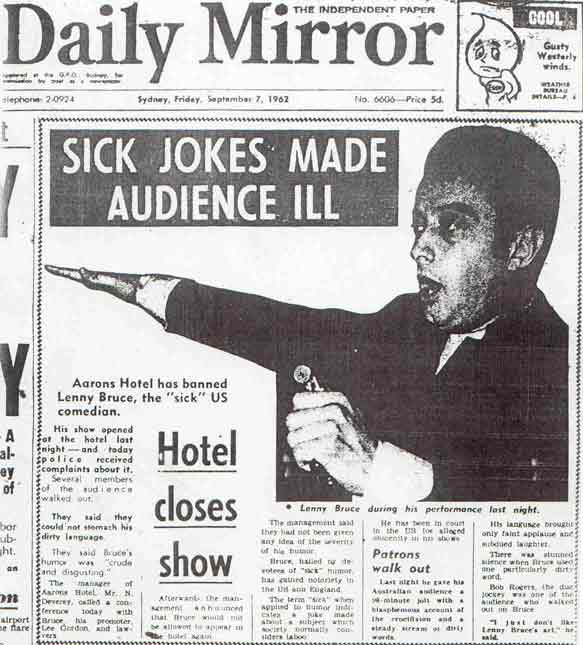

Lenny was called a ‘sick comic,’ though he insisted that it was society which was sick and not him. He was called a ‘dirty comic’ though he never used a word you and I have not heard since our childhood. His tangles with the law over the use of these words and his arrests on narcotics charges were the only two things that the public really knew about him. Mass media saw to that.

When he was in Mission General Hospital in San Francisco, the hospital announced he had screamed such obscenities that the nurses refused to work in the room with him, so they taped his mouth shut with adhesive tape. The newspapers revelled in this and he was shown on TV, his mouth taped and his eyes rolling in protest, being wheeled into the examining room. Words that nurses never heard?

What new phrases he must have invented that day, what priceless epiphanies lost to history now forever. Once, in a particularly poignant discussion of obscenity on stage, Bruce said, ‘If the titty is pretty it’s dirty, but not if it’s bloody and maimed . . . that’s why you never see atrocity photos at obscenity trials.’ He used to point out, too, that the people who watched the killing of the Genovese girl in Brooklyn and who didn’t interfere or call a cop would have been quick to do both if it had been a couple making love. ‘A true definition of obscenity,’ he said, ‘would be to sing about pork outside a synagogue.’

Bruce found infinity in the grain of sand of obscenity. From it he took off on the fabric which keeps all our lives together. ‘If something about the human body disgusts you,’ he said, ‘complain to the manufacturer.’ He was one of those who, in Hebbel’s expression, ‘have disturbed the world’s sleep.’ And he could not be forgiven.”