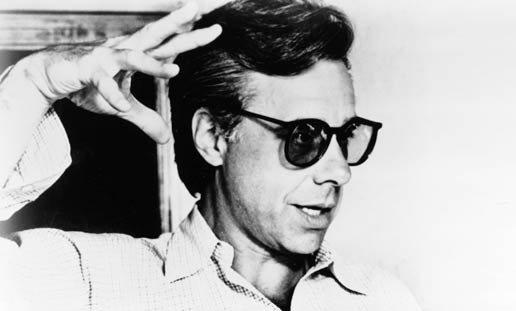

Posting an interview earlier with Peter Bogdanovich reminded me of “Death of a Playmate,” Teresa Carpenter’s searing, Pulitzer Prize-winning Village Voice article, which not only excoriated the estranged husband of Dorothy Stratten, who brutally murdered the Playboy centerfold and actress in 1980, but also pilloried Bogdanovich and Hugh Hefner for the objectification and commodification of the young woman. Of course, Carpenter, who later sold the rights to her article to Bob Fosse to serve as the basis of Star 80, could be accused of the latter herself. The piece’s opening:

It is shortly past four in the afternoon and Hugh Hefner glides wordlessly into the library of his Playboy Mansion West. He is wearing pajamas and looking somber in green silk. The incongruous spectacle of a sybarite in mourning. To date, his public profession of grief has been contained in a press release: “The death of Dorothy Stratten comes as a shock to us all. . . . As Playboy’s Playmate of the Year with a film and television career of increasing importance, her professional future was a bright one. But equally sad to us is the fact that her loss takes from us all a very special member of the Playboy family.”

That’s all. A dispassionate eulogy from which one might conclude that Miss Stratten died in her sleep of pneumonia. One, certainly, which masked the turmoil her death created within the Organization. During the morning hours after Stratten was found nude in a West Los Angeles apartment, her face blasted away by 12-gauge buckshot, editors scrambled to pull her photos from the upcoming October issue. It could not be done. The issues were already run. So they pulled her ethereal blond image from the cover of the 1981 Playmate Calendar and promptly scrapped a Christmas promotion featuring her posed in the buff with Hefner. Other playmates, of course, have expired violently. Wilhelmina Rietveld took a massive overdose of barbiturates in 1973. Claudia Jennings, known as “Queen of the B-Movies,” was crushed to death last fall in her Volkswagen convertible. Both caused grief and chagrin to the self-serious “family” of playmates whose aura does not admit the possibility of shaving nicks and bladder infections, let alone death.

But the loss of Dorothy Stratten sent Hefner and his family into seclusion, at least from the press. For one thing, Playboy has been earnestly trying to avoid any bad national publicity that might threaten its application for a casino license in Atlantic City. But beyond that, Dorothy Stratten was a corporate treasure. She was not just any playmate but the “Eighties’ first Playmate of the Year” who, as Playboy trumpeted in June, was on her way to becoming “one of the few emerging film goddesses of the new decade.”

She gave rise to extravagant comparisons with Marilyn Monroe, although unlike Monroe, she was no cripple. She was delighted with her success and wanted more of it. Far from being brutalized by Hollywood, she was coddled by it. . . . “Playboy has not really had a star,” says Stratten’s erstwhile agent David Wilder. “They thought she was going to be the biggest thing they ever had.”

No wonder Hefner grieves.

“The major reason that I’m . . . that we’re both sittin’ here,” says Hefner, “that I wanted to talk about it, is because there is still a great tendency . . . for this thing to fall into the classic cliche of ‘small-town girl comes to Playboy, comes to Hollywood, life in the fast lane, and that somehow was related to her death. And that is not what really happened. A very sick guy saw his meal ticket and his connection to power, whatever, etc. slipping away. And it was that that made him kill her.”

The “very sick guy” is Paul Snider, Dorothy Stratten’s husband, the man who became her mentor. He is the one who plucked her from a Dairy Queen in Vancouver, British Columbia, and pushed her into the path of Playboy during the Great Playmate Hunt in 1978. Later, as she moved out of his class, he became a millstone, and Stratten’s prickliest problem was not coping with celebrity but discarding a husband she had outgrown. When Paul Snider balked at being discarded, he became her nemesis. And on August 14 of this year he apparently took her life and his own with a 12-gauge shotgun.•

___________________

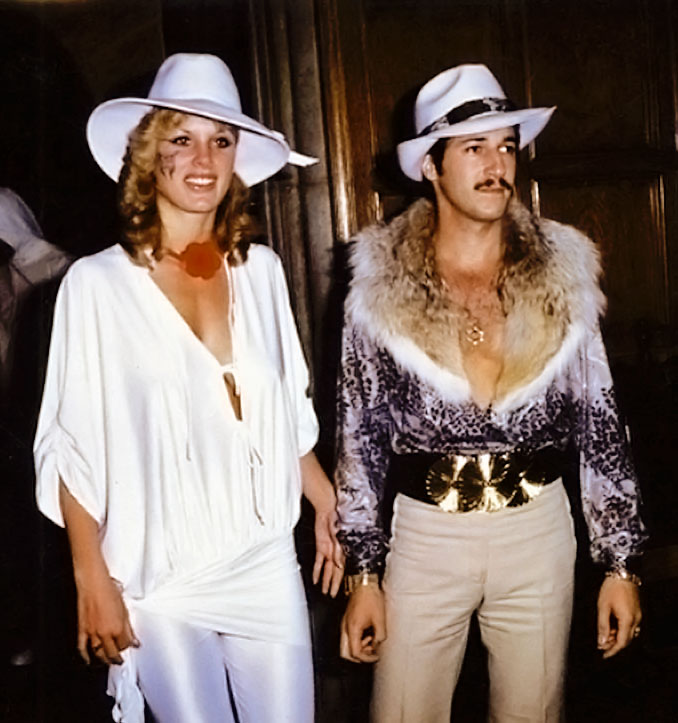

Dorothy Stratten visits Johnny Carson in 1980, four months before her murder.