From a 1968 Pete Hamill report in Ramparts about the Summer Olympics in Mexico City, the Games of Tommy Smith and John Carlos’ Black Power salute but also of George Foreman’s flag-waving:

“HE FIRST BLACK SCOURGE of the Republic to appear at the games was Jim Hines, who won the 100 meters in the world record time of nine and nine-tenths seconds. Hines opposed San Jose State College Professor Harry Edwards’ proposed boycott, but let it be known that under no circumstances would he accept his medal if Avery Brundage was the man awarding it. Avery Brundage did not award the medal.

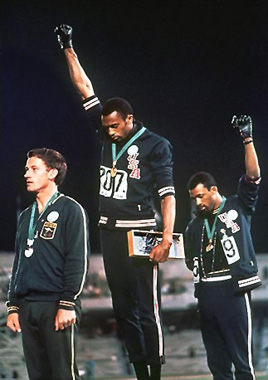

But the real confrontation was yet to come, and it came from John Carlos and Tommie Smith, who were running in the 200-meter dash. It began when they wore long black socks (later changed to ankle socks, to prevent cutting circulation in the legs) in preliminary heats. They went on to win with Smith finishing first, in a blazing 19.8, setting a new world record. Smith might have peeled another few tenths off the record had he not raised his arms in exultation as he crossed the finish line. Carlos finished third, behind Australian Peter Norman.

When they came out for the award ceremony, they walked without shoes, carrying a track shoe in one hand, with the other hand tucked into their windbreakers. They climbed the stand, and then, after receiving the medals, they turned toward the American flag as the Star Spangled Banner was played. They took their hands out. Smith’s right hand wore a black glove, Carlos’ left hand its mate. As the anthem played, they bowed their heads and raised their gloved hands to the sky in a clenched fist salute. Thirty hours later they were kicked off the team.

At this point the Olympic team almost collapsed. Carlos, who couldn’t stop talking before the protest, now wouldn’t talk to anyone. He stomped back and forth through the Olympic Village, followed by reporters and cameramen, and he even threatened to punch one of them. Smith, who had finished first, was less available than Carlos. In front of Building II, more than 100 people assembled while Roby tried to explain what had happened. The members of the committee had met (‘How many blacks on that committee?’ someone shouted) and decided that the two members of the team had violated the Olympic tradition of sportsmanship by their ‘immature’ conduct (‘What rule did they break?’ shouted Joe Flaherty of the Village Voice.) The crowd was told that if strong action was not taken, the American team would be completely disqualified.

A banner saying ‘Down with Brundage’ fluttered from the seventh floor of the American dormitory; on the fourth, a Wallace for President bumper sticker appeared. The seventh floor housed the black track athletes; the fourth floor housed the rifle team.

When Lee Evans, Larry James and Ron Freeman finished one-two-three in the 400 meters, everyone waited to see what they would do. They wore Black Panther berets because, said Evans, who had been in tears over the dismissal of his teammates, ‘It was raining.’ But they were not thrown off the team. They were still needed for the 1600-meter relay. Smith and Carlos had not been needed for anything.

The protest of the black athletes was more muted than had been expected. But the people on the IOC, and especially the members of the American Committee, seemed terrified. Something even as restrained as the gesture of Smith and Carlos had never happened before. They had always before been able, in Roby’s phrase, to ‘control’ their athletes.“