Fears about declining America innovation is a cyclical concern, not something that started with Peter Thiel. Thirty-five years ago, then-MIT President Paul Edward Gray believed if the sky wasn’t falling then it had at least darkened. Gray was right that smaller companies were about to explode into behemoths and elbow aside traditional giants, but his worries about regulation seem to have been excessive. And he clearly couldn’t have anticipated China’s rise.

Of course, the most honest response to the question “So there will be no more individual inventors like Edison?” is that Edison and other larger-than-life industrialists never were individual inventors. That was mostly a “Great Man” narrative. From Gail Jennes’ 1980 People interview with Gray:

Question:

What is happening to the spirit of innovation in America?

Paul Edward Gray:

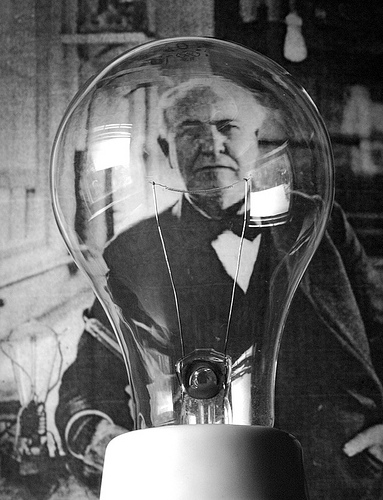

The increasing complexity of the systems we work with makes innovation ever more difficult. It requires larger investments in laboratories, equipment and people—and more sophistication in all of them. Not that inventing a practical light bulb looked simple to Edison around 1879 when he did it; but it was physically a lot less complex than, say, what Edwin Land faced when he invented instant photography in 1947. And that, in turn, seems simple in comparison with some of the challenges facing us today.

Question:

So there will be no more individual inventors like Edison?

Paul Edward Gray:

Well, in the last decade or two it’s become harder for an inventor to bring a new idea into the marketplace. It’s not just a matter of the light bulb turning on over somebody’s head, as in the cartoons. The innovator has to think about the problems of marketing, sales, controlling the manufacturing process and, not least, meeting the demands of government regulatory agencies.

Question:

Then who is replacing the old-fashioned inventor?

Paul Edward Gray:

Small companies like Alza Corp., a pharmaceutical company in California, and Florida’s LaserColor Laboratories. The large corporations have the means to innovate, but they develop an investment in the present—a mindset which values stability and resists the introduction of radically different ideas. Take the transistor, or semiconductor, as an example. None of the companies that made vacuum tubes 30 years ago is significant in semiconductors today. The ability to invent and the ability to capitalize on invention are often two radically different things. …

Question:

In terms of innovation, is the U.S.S.R. gaining on us?

Paul Edward Gray:

Basic science there in many respects is very good. In certain areas, such as fusion research, they’ve been in the forefront. But that’s not true of their technology. Why is the U.S.S.R. so interested in buying large-scale and medium-size computers? Because they can’t make their own. They can hand-tailor a few for military installations, but they can’t produce modern, fast digital processors like we can. The Soviets will not be our competitors in any high-technology world market in the foreseeable future. The same thing is true of China, in spades. I visited Peking last summer, and their computer, chemical and engineering sciences are 20 years or more behind. They’ll have a tough time catching up.

Question:

Who will be our competitors?

Paul Edward Gray:

A few Western European countries, principally Germany. Also Japan. And maybe in the near future some other Far East nations. Taiwan, for instance, has developed at a tremendous clip. So has South Korea.

Question:

Are you optimistic about the future of science in the U.S.?

Paul Edward Gray:

Someone once said that the difference between the optimist and the pessimist is that the pessimist understands things better. I’m not sure I agree. I guess I am an optimist. A large part of the answer lies in training the scientists and engineers of the 1980s and 1990s to deal with novelty and uncertainty. At MIT, we’re in the right place at the right point in history to make a difference. I hope we can.•