The Humanities has had “physics envy” for quite awhile, trying to turn literature and such into a science for some silly reasons rooted in insecurity. It’s probably less understood outside academic circles that AI also long hoped to be like physics, wrapping up staggering complexities into a few laws. Marvin Minsky wasn’t a believer in such tidiness. A Fold article collects thoughts about the recently deceased AI pioneer from some of his colleagues. One, MIT Professor Patti Maes, recalls his parrying with popular beliefs in the field. An excerpt:

The Humanities has had “physics envy” for quite awhile, trying to turn literature and such into a science for some silly reasons rooted in insecurity. It’s probably less understood outside academic circles that AI also long hoped to be like physics, wrapping up staggering complexities into a few laws. Marvin Minsky wasn’t a believer in such tidiness. A Fold article collects thoughts about the recently deceased AI pioneer from some of his colleagues. One, MIT Professor Patti Maes, recalls his parrying with popular beliefs in the field. An excerpt:

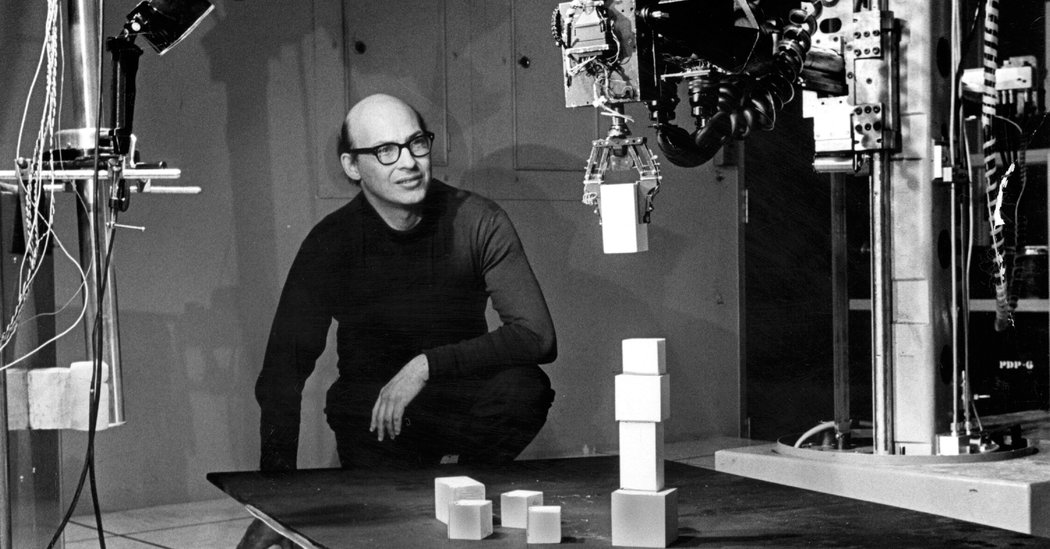

Explorations of Consciousness and Longevity

Some of Marvin’s most fascinating work was around the idea of the Mind As Society and the nature of consciousness. Throughout this work, what stood out was his enormous respect for the human.

“When a person says ‘I’m not a machine’, they’re showing a lack of respect for people….because we are the greatest machine in the world.”

He was curious about the fuzzy ideas people hold about the nature of consciousness and marveled at how we can effectively navigate the world without the slightest idea of how we were doing it.

“The mystery of consciousness to me is not ‘Isn’t it wonderful that we’re conscious’, but it’s the opposite. Isn’t it wonderful that we can do things like talk and walk, and understand without having the slightest idea of how it works.”

He also focused on health and longevity, speaking of immortality as a perfectly reasonable goal. He thought deeply about everything from the priorities we should have as a species to body part replacement.

From Pattie Maes:

“Marvin was always a true original, out-of-the-box thinker. While he is of course widely recognized as one of the founders of the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI), his views were often at odds with the majority of the AI community.

For many decades, and even today, AI was plagued by “physics envy.” Researchers sought a few universal principles or mechanisms that could model or produce human-like intelligence. Marvin constantly reminded us that the real solution was likely to be a lot more complex. He described a myriad of different mechanisms that may be involved in producing intelligence in his books ‘The Society of Mind’ and ‘The Emotion Machine’ and emphasized the importance of giving computers large amounts of ‘common sense knowledge’, a problem few AI researchers, even today, have attempted to tackle.

I suspect that gradually the field will come to align with his views, recognizing that his views and writings have a timeless and deep quality.”•