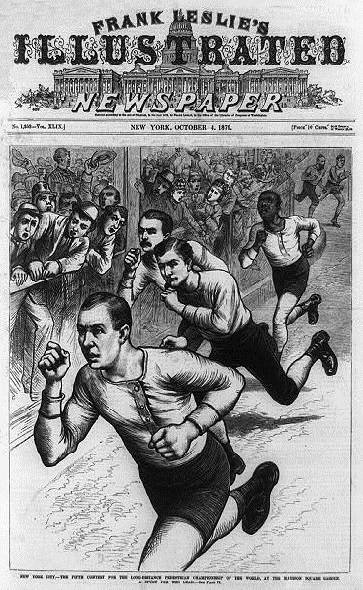

When the world was slower, much slower, a quick gait could bring in a huge gate. Such was the case with pedestrianism, a sensation before automobiles were king of the roads, in which competitors would race-walk cross-country or do ceaseless laps around a track in an arena before bleary-eyed spectators who would spend up to a week mesmerized by the exhibition of slow-twitch muscle fiber. An excerpt from a report in the March 4, 1882 Brooklyn Daily Eagle about one such six-day contest, a cross between a footrace and a dance marathon, before a large Madison Square Garden audience that alternately yelled and yawned:

Popular interest in the race of the champions touched its highest point to-day. The opening of the last day of the walk was witnessed by over two thousand spectators. Fully one-half of these had lingered in Madison Square Garden all night. Drowsy and unkempt, with grimy faces and dusty apparel, they shivered behind their upturned coat collars, determined to see the battle out. The management’s order of ‘no return checks’ had far more unpleasant significance for them than hours of discomfort in the barnlike building. The permanent lodger in a six days’ match usually makes his bed upon a coal box, in a grocery wagon or beneath the roof of the police lodging room. Accordingly, it is his habit to come to the garden at the beginning of a race and remain for a full week, or until he is removed by the employees to make way for some more profitable customers. This contest had its full share of these persistent individuals. Beside them, many sporting men remained until almost daybreak, attracted by the enormous scores rolled up by the pedestrians and speculations as to what they would do in the way of the beating of the record. It was conceded that Hazael and Fitzgerald would surpass all previous performances. Hazael’s wonderful work was generally regarded as the marvel of the match.

When Hazael, the Londoner of astonishing prowess, retired from the track at 11:37 last night, he had rolled up the enormous record of 540 miles in 120 hours. To his enthusiastic handlers in walker’s row he complained of feeling tired and sleepy. His limbs were sound and apparently tireless as steel. He partook heartily of nourishment and then, throwing himself on his couch, caught a few cat naps. At 1:49:20 he bounded out of his flower covered alcove, and once more took up the thread of his travels. His rest of two hours and twelve minutes had greatly improved him. He had been sponged and rubbed, and grinned all over his quaint face at his enormous score. That he was yet full of vigor and energy was apparent from the work he immediately entered upon. He had not walked more than half a lap when he gave a preliminary wobble. Then he clasped his hands over his ears, pulled his head down until his slender neck was well craned, and shot over the yellow pathway at a rattling pace. The sleepy watcher pricked up their ears at the shout which greeted this performance, and a fusillade of handclapping shook the garden. Fitzgerald was jogging over the tanbark at this time, sharply working to draw nearer to the Englishman’s figures on the scoring sheets. He accelerated his speed as the Londoner resumed the task before him. Within a few minutes both men were running like reindeer. It is doubtful they could have made better time if a pack of famished wolves had been at their heels. Volley after volley of applause thundered after them from the spectators. The runners kept close together. Between the hours of 2 and 8 o’clock this morning, so swift was their movements, that each man had added six miles and seven laps to his score or within one lap of seven miles. The struggle became so intense that the spectators began to realize that something unusual was in progress. A stir was apparent all over the vast interior and wearied humanity pushed itself to the rail to see what was going on.•