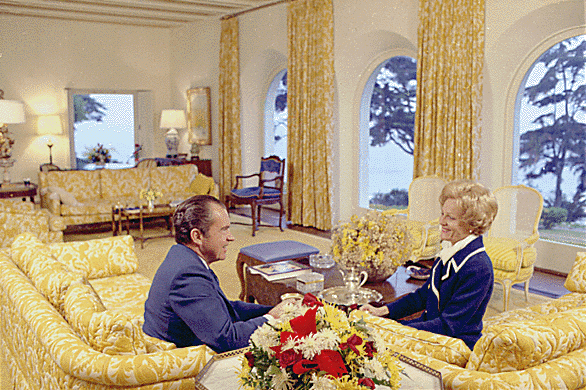

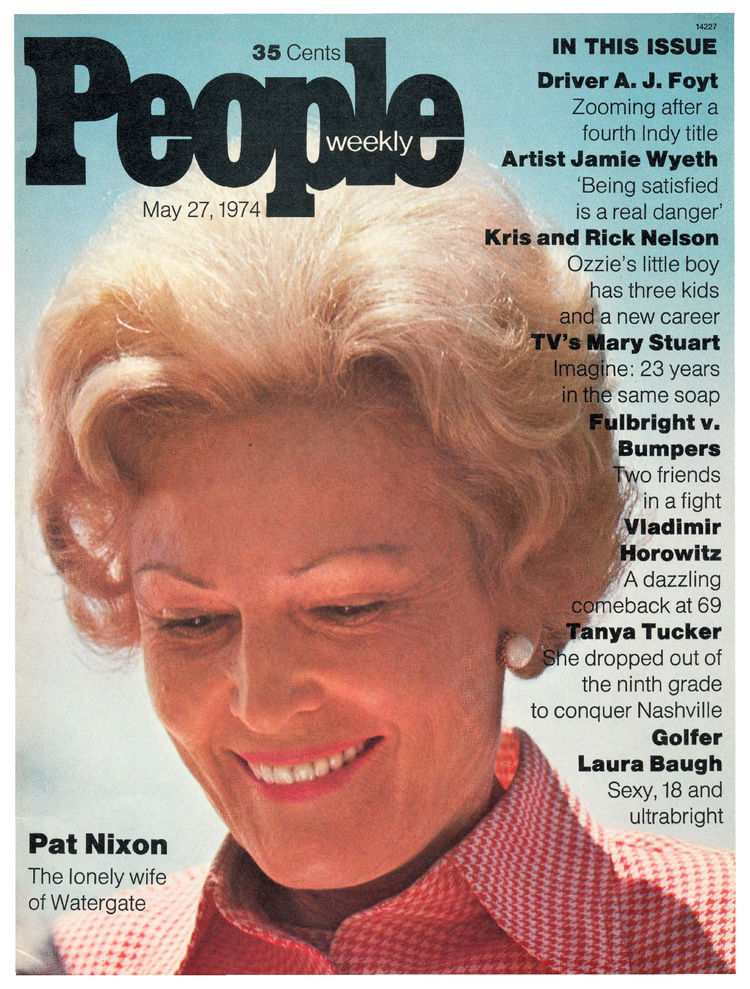

In his day, Richard Nixon was more of a Liberal in most ways than Barack Obama, though it isn’t completely sensible to measure Presidents outside of the era in which they serve. For all his enthusiasm for universal healthcare and racial quotas, Nixon was hated by the Left, and justifiably so, for his handling of Vietnam and his paranoia about the press, campus activists, anti-war demonstrators, the Black Power movement, Women Libbers, the Democratic National Committee, and, well, everything. He had no reason to fear on the homefront, however, where he enjoyed the unwavering support of his spouse, Pat, who was orphaned as a teenager and would not allow a second family to slip from her grasp. From “Watergate Wife,” a May 1974 People article about the First Lady less than three months before her husband became the only U.S. President to resign:

“Even among her staunchest supporters, the question about Patricia Nixon lingers. As visitors queue up to greet her in the Blue Room or crowds press around her at airport rallies, the unspoken curiosity is there: How does she hold up? How can she survive the bruising stress of Watergate?

‘Get it out of your head that this is a woman who takes to her bed with smelling salts,’ cautions a woman reporter who sees her often. ‘Pat Nixon is the tough one in that marriage.’

That is quite a testimonial. While Richard Nixon built his political reputation on toughness, Pat has always seemed the fragile partner. An intensely private woman, married for nearly 34 years to one of the most public of men, she has endured a succession of taxing campaigns behind a facade of smiling good humor. Even now, as President Nixon battles to stay in office during what may be the climactic crisis of a stormy career, his wife has dutifully kept up appearances. Although increasingly wary of the press, she conscientiously tends to ceremonial functions and continues to show her smile like the flag.

Despite her insistence on toughing out Watergate, Mrs. Nixon, of course, has been feeling the pressure. She made herself a virtual recluse in the White House throughout much of the winter, retreating within her family for solace. Only in March, on a goodwill visit to Latin America, did she appear to blossom with a sense of release. The hectic six-day trip afforded her both a reprieve from the solitude and relief from the drumfire of Watergate. When a reporter intruded on her new ebullience by asking about ‘the strain’ of the past year in Washington, she recoiled with a look of dismay. ‘I don’t really wish to speak of it,’ she said abruptly, then added, ‘You all drink some champagne.’

Pat Nixon has long been regarded as a sort of auxiliary personality in Washington—a presidential appendage with little of the lively independence that Jackie Kennedy and Lady Bird Johnson brought to the position of First Lady. Although, paradoxically, she has only two or three close friends outside her family, she seems comfortable among welcoming crowds especially when she is alone, out from under her husband’s shadow. Plunging into a happy sea of strangers, she bubbles over with chatter and cheerfulness and exudes a casual warmth that the President lacks.

But it is endurance that is her own special pride. Once committed, she never breaks an engagement—’I do or die,’ she says. ‘I never cancel out,’—and rarely is so much as a hair out of place. Her secret, she confides, is an ability to deny the demands of her senses. ‘I hate complainers,’ she says, ‘and I made up my mind not to be one. So if it’s cold, I tell myself it’s not cold, and if it’s hot, I tell myself it’s not hot. And you know, it works!’

Her stoical tolerance of discomfort, however, does not extend to critical comment about her husband. It is the vulnerable side of her own personal strength. Her schedule of White House duties—greeting the poster child of the month, playing host to women’s groups—is carefully drawn to avoid embarrassing confrontations. Her mail is likewise thoroughly screened. She rarely grants interviews and is constantly on guard against even the most innocuous questions. Recently, a reporter asked innocently if she were looking forward to going to Europe, should the President decide to visit there soon. ‘You never know what’s going to happen,’ she replied with her mask of a smile. ‘You live for each day.’ It is understandable, perhaps, that after years of warring between the President and the Washington press corps, she should regard the media with instinctive distrust. ‘It’s right out of The Merchant of Venice,’ she recently told her close friend Helene Drown in a discussion of Watergate repercussions. ‘They’re after the last pound of flesh.'”