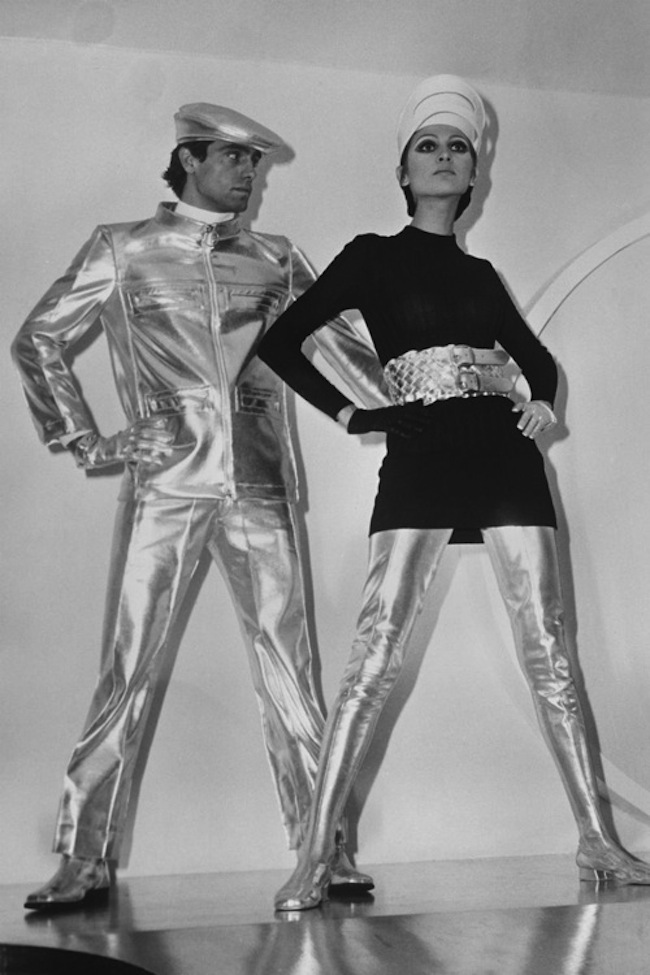

The space-age period of Pierre Cardin the 1960s and early 1970s was one of the greatest bursts of creativity anyone has ever enjoyed. It still seems to me a step ahead of anything Hollywood wardrobe departments are doing today. In 1976, when he was 54 years old and the master of not a fashion house but an empire, the designer was profiled in People by Pamela Andriotakis. The opening:

“‘In the beginning, they always criticize me,’ Pierre Cardin says gleefully. ‘They say, ‘What is he doing now? Quel horreur? Quel décadence. That’s the end of Cardin.’ Then, six months later, they’re all doing it.’

The 54-year-old Frenchman is more right than humble. Not only did his flamboyant men’s clothes lead to the ‘Peacock Revolution’ of the 1960s and his ready-to-wear designer fashions for women lower the brows of haute couture, he also has inspired many of his fellow couturiers to venture into entrepreneurial areas far removed from clothing.

Few, however, have extended themselves as much as Cardin, whose $100-million-a-year operation is responsible for, among other things, Cardin towels, Cardin stereo sets, Cardin kitchens, Cardin glassware, Cardin bicycles, Cardin carpets, Cardin lamps, Cardin ashtrays, Cardin wallpaper, Cardin wines and Cardin chocolates.

‘The next thing you know he’ll be designing cheese,’ huffed an executive at archcompetitor Yves St. Laurent. ‘Cardin is no longer a label,’ exults Cardin himself. ‘It is a trademark.’

The trademark is used by 280 factories with 60,000 employees, located in 51 countries on six continents. Only Antarctica has thus far escaped the impact of what the French have come to call Cardinization. (And no one is betting against the likelihood of a Cardin penguin leash.)

While most of the Cardin products are manufactured under licensing arrangements, Cardin is more than just the man behind the scene. He is all over the scene. On a typical day he leaves his Paris townhouse after breakfast—assuming he remembers to have breakfast—and walks to his office at 59 Rue du Faubourg St. Honoré, the Right Bank street of exclusive shops. There are morning meetings with directors of his foreign companies, followed by briefer consultations with textile makers and other suppliers, many of whom fly to Paris from all over Europe just to aim a 15-minute sales pitch at Cardin.

Between appointments, Cardin may lope upstairs to his fashion workroom to tinker with a detail on a garment from a forthcoming line. Cardin claims responsibility for all original designs, which are then executed by subordinates under his watchful eye. Cardin has also maintained his presence at formal showings—the latest one, his spring-summer line, was unleashed four months ago in Paris—even though his ready-to-wear business is the most profitable sector of his empire. ‘Actually,’ he says, ‘we lose money on haute couture. But it is a great laboratory for ideas.’

In the sparsely furnished, white-walled workroom, he gives brief audiences to employees with questions or suggestions, talking little but gesturing with Mediterranean expansiveness. When a supervisor approached him to pass on an employee’s request for a raise, Cardin said crisply, ‘Give it to him. He has worked for me for many years.” Another employee says, ‘You have to have a sixth sense to work for him. It is very tiring. But he is the best school in the world.’

After perhaps 15 meetings, it is time for lunch, which he often eats on a plane bound for the South of France, England or Italy en route to visiting a factory. He may be back in his offices by late afternoon, checking stocks in his three nearby boutiques, going over the books, rearranging furniture or even, with a kind of frenetic energy, sweeping up a messy room.

In especially busy times Cardin has been known to go on work binges, wearing the same suit and tie for several days, neglecting to shave and generally becoming a less than persuasive advertisement for the Cardin look. When less pressed, Cardin often spends the evening at his version of Xanadu, l’Espace (‘Space’), a combination theater and exhibition hall which he opened in December 1970.

Cardin recently turned l’Espace into a Sarah Bernhardt museum. He has also used it to introduce new painters, sculptors and playwrights as well as to present such established performers as Ella Fitzgerald, Marlene Dietrich and Dionne Warwicke. He is said to lose $300,000 a year on I’Espace but is more than compensated in personal enjoyment—not to mention good public relations. The couturier André Courrèges, who admires the way Cardin operates, says, ‘He does it because it is his mistress.'”