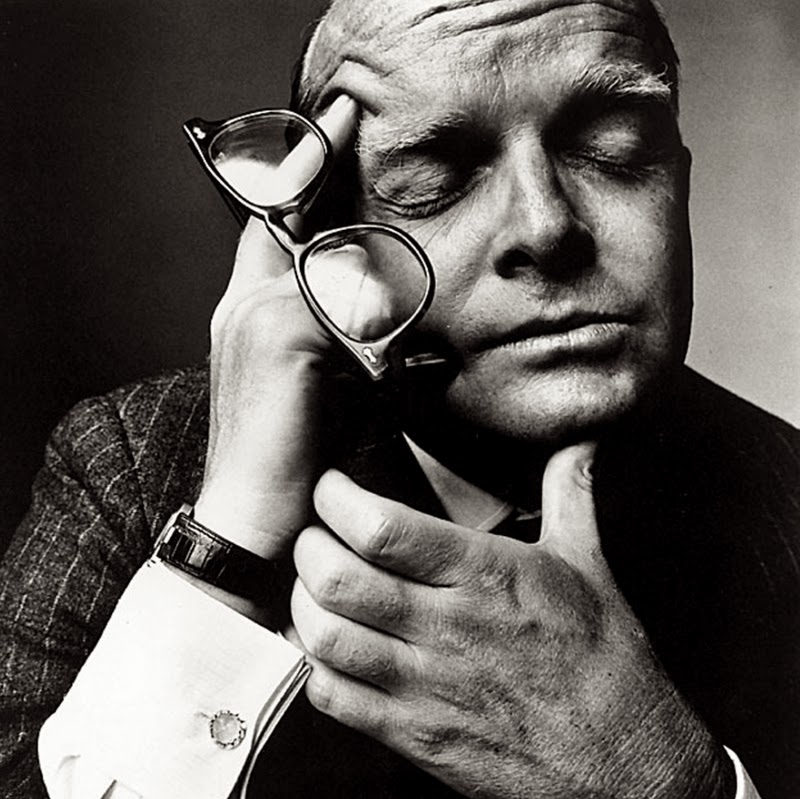

Truman Capote’s final, uncompleted novel, Answered Prayers, the one that was excerpted in Esquire in the 1970s and destroyed his social life, was never published in full. No one is totally sure where the hundreds of pages reside, but it’s believed they’re languishing in an unknown California bank security-deposit box, waiting to be found. At least that’s the theory put forth in Sam Kashner’s recent Vanity Fair piece, “Capote’s Swan Dive“:

“After Capote’s death, on August 25, 1984, just a month shy of his 60th birthday, Alan Schwartz (his lawyer and literary executor), Gerald Clarke (his friend and biographer), and Joe Fox (his Random House editor) searched for the manuscript of the unfinished novel. Random House wanted to recoup something of the advances it had paid Truman—even if that involved publishing an incomplete manuscript. (In 1966, Truman and Random House had signed a contract for Answered Prayers for an advance of $25,000, with a delivery date of January 1, 1968. Three years later, they renegotiated to a three-book contract for an advance of $750,000, with delivery by September 1973. The contract was amended three more times, with a final agreement of $1 million for delivery by March 1, 1981. That deadline passed like all the others with no manuscript being delivered.)

Following Capote’s death, Schwartz, Clarke, and Fox searched Truman’s apartment, on the 22nd floor of the U.N. Plaza, with its panoramic view of Manhattan and the United Nations. It had been bought by Truman in 1965 for $62,000 with his royalties from In Cold Blood. (A friend, the set designer Oliver Smith, noted that the U.N. Plaza building was ‘glamorous, the place to live in Manhattan’ in the 1960s.) The three men looked among the stacks of art and fashion books in Capote’s cluttered Victorian sitting room and pored over his bookshelf, which contained various translations and editions of his works. They poked among the Tiffany lamps, his collection of paperweights (including the white rose paperweight given to him by Colette in 1948), and the dying geraniums that lined one window (‘bachelor’s plants,’ as writer Edmund White described them). They looked through drawers and closets and desks, avoiding the three taxidermic snakes Truman kept in the apartment, one of them, a cobra, rearing to strike.

The men scoured the guest bedroom, at the end of the hallway—a tiny, peach-colored room with a daybed, a desk, a phone, and lavender taffeta curtains. Then they descended 15 floors to the former maid’s studio, where Truman had often written by hand on yellow legal pads.

‘We found nothing,’ Schwartz told Vanity Fair. Joanne Carson claims that Truman had confided to her that the manuscript was tucked away in a safe-deposit box in a bank in California—maybe Wells Fargo—and that he had handed her a key to it the morning before his death. But he declined to tell her which bank held the box. ‘The novel will be found when it wants to be found,’ he told her cryptically.”