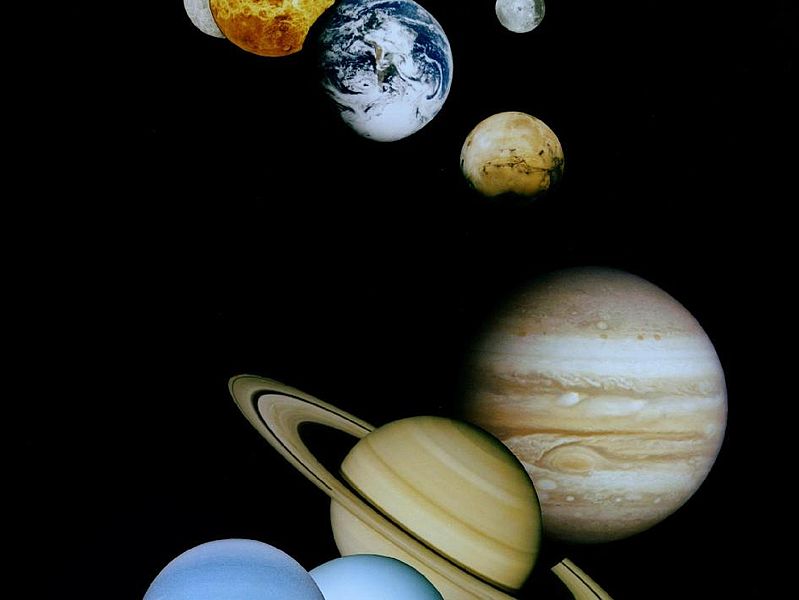

A decked-out space habitat peopled by Earthlings may grace the moon or Mars or some other mass during the twenty-first century, offering a chance for zero-gravity sex and retirement far from the kids. If it is to be, much of the infrastructure and architecture probably needs to be built with found materials being fed into 3D printers. From Oliver Burkeman at the Guardian:

Inflatables have come a long a way since the 1960s, when Nasa commissioned tyre company Goodyear to design an enormous galactic inner tube. The 9m-wide rubber doughnut never made it into space, but it proved to be a huge inspiration to others – including Guillermo Trotti, then an enthusiastic architecture student in search of a thesis project, who designed a seminal proposal for an inflatable habitat on the moon in 1974. His Counterpoint lunar colony, a model of which now resides in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, envisaged a network of inflated domes and structures moulded from lunar basalt to house a community of 200 people, sustained by an ecosystem of soybean plants, trout, catfish, 200 chickens and 50 miniature goats.

“It was a wild dream at the time,” he says. “But it caught the eye of [architect] Buckminster Fuller and I won a Nasa research grant to develop it. Now, 40 years on, it doesn’t seem such a crazy idea.” Trotti went on to co-found the Sasakawa International Center for Space Architecture, which offers what is still the world’s only space architecture masters programme. Every year, its students’ projects push Nasa scientists to dream a little bit further, with provocative visions for Mars landers lowered from hovering “skycranes” and spacecraft propelled on long tethers to create artificial gravity.

“If you look at the history of the industry, what we do in space is really a mirror for our contemporary values on earth,” says Neil Leach, who edited a recent issue of Architectural Design devoted to space architecture. “The Apollo mission was part of the cold war, the ISS was a defining moment of international collaboration, and now we’re seeing private entrepreneurs really leading the way, with companies like SpaceX [founded by PayPal billionaire Elon Musk] and Blue Origin [founded by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos]. Reflecting our earthly priorities, environmental sustainability is now top of the space agenda.”

The current buzzword in Nasa circles is ISRU, or in-situ resource utilisation, the space equivalent of using locally available materials.•