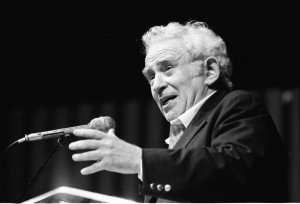

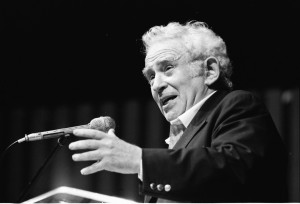

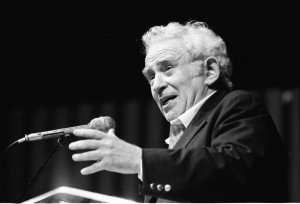

Rip Torn: And then the blood streamed down Norman Mailer's face. Good times, good times.(Photo by Alan Light.)

Norman Mailer starred as a porn director running for President in Maidstone, the largely improvised 1970 clusterfuck of a film he directed over four days in the Hamptons. The movie itself is something of a time warp, but in any era the conclusion would be unsettling; Mailer and his actor Rip Torn managed to turn it into a very real bloodbath.

Rip Torn recalls for writer Harold Conrad the film’s insane ending in the December 1985 issue of Spin. An excerpt from the article entitled “RIP,” in which the writer and his volatile subject recall those magical moments:

“‘Okay, so now you’re doing Mailer’s film, Maidstone, which leads us into another one of your dilemmas when you hit Mailer on the noggin with a hammer in the final scene of the picture.

‘You make it sound like an assault. You have to know the facts.’

‘Remember me, Rip,’ I say. ‘I was there and it was an assault. That’s what it was supposed to be!’

‘That’s right! I remember now. You were there, but we never had much of a chance to talk.’

Norman Mailer: So I bit Rip Torn's ear and he bled like a stuck pig. (Image from MDCarchives.)

It seemed to me that everybody was there. There must have been a hundred people in that picture–actors, writers, society dames, politicians. The whole project, on and off the screen, was the wildest scene I’d ever been around.

‘Now if you recall,’ says Rip, ‘there was no screenplay for Maidstone. It was all improvisation. It was always agreed that at some point someone would have to kill this porny director. Norman had the role. I had gone over this with him. He knew that. And here we were, shooting the final scene of the picture, and he was still alive!”

‘Didn’t you think you’d hurt him, hitting him on the head with a hammer?’

‘I knew it would just bruise him a little bit, but we were shooting for realism. That’s what the picture was all about. I had to make it look like I hit him hard enough to kill him, but I had control of the hammer. It was really just a tap.’

‘Some tap. the blood was streaming down his face. Then you two started to grapple. Norman sunk his teeth into your ear, and you started to bleed like a stuck pig. There was blood all over the place, real blood.'”