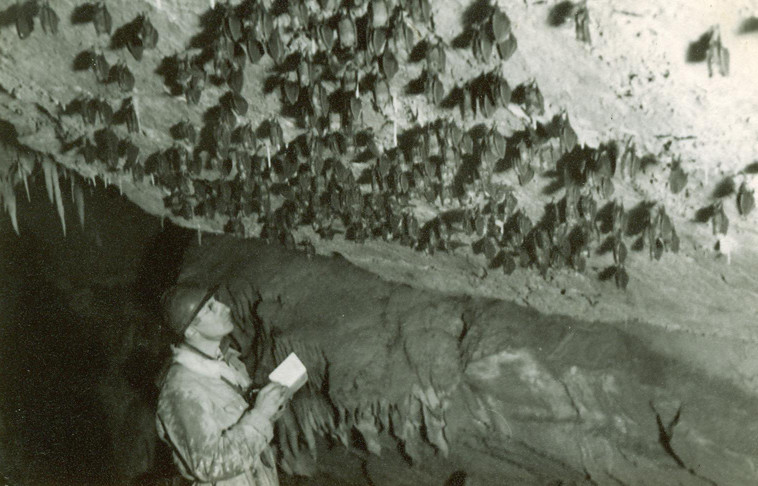

Norbert Casteret, speleologist, took a giant leap for humankind in 1923 with a dive in the Grotte de Montespan in France. This brave departure from dry land led to one of the adventurer’s greatest discoveries (one of anyone’s greatest): a trove of prehistoric drawings and sculptures of animals. In his book, Ten Years Under The Earth, Casteret recalls the moment he shared with friend and fellow explorer Henri Godin:

At that moment I stopped before a clay statue of a bear, which the inadequate light had thus far hidden from me; in a large grotto a candle is but a glow-worm in the inky gloom.

I was moved as I have seldom been moved before or since: here I saw, unchanged by the march of aeons, a piece of sculpture which distinguished scientists of all countries have since recognized as the oldest statue in the world.

My companion crawled over at my call, but his less practised eye saw only a shapeless chunk where I indicated the form of the animal. But one after another, as I discovered them around us, I showed him horses in relief, two big clay lions, many engravings.

That convinced him, and for more than an hour discovery followed discovery. On all sides we found animals, designs, mysterious symbols, all the awe-inspiring and portentous trappings of ages before the dawn of history.•

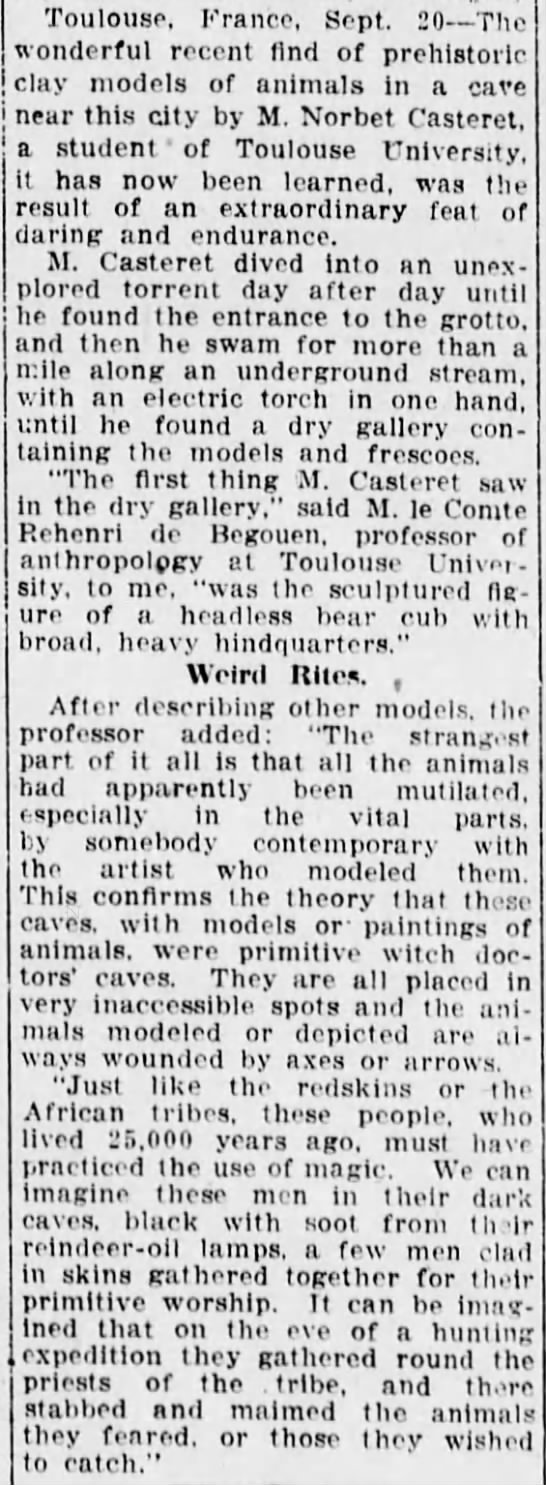

The following is an October 7, 1923 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article about the Upper Paleolithic trove, which focuses on clay figures that had been mutilated by their creators as part of a hunting ritual.