Fifty Great Articles From 2017

It’s December, which means it’s time for me to collect my favorite print journalism of the year, which, in 2017, was an especially rich assortment of articles that saw an embattled industry (mostly) rise to meet a raft of dizzying challenges, including democracy itself hanging in the balance. It was a stunning period of reformation, provoked in good part by the likely illicit election to President of a racist, traitorous predator.

Let’s remember it wasn’t social media or search engines that took down the previously untouchable Harvey Weinstein but rather two very expensive pieces of reportage by legacy news organizations. As Facebook, Google and other Silicon Valley behemoths continue to fail, through indifference or incompetence, to support civil society, Sheryl Sandberg summarized the role of our new communications giants in the most tone-deaf manner: “At our heart we’re a tech company—we don’t hire journalists.” Thankfully, some companies do, and after this year, it’s clearer than ever that characters, 140 or even 280, mean little when divorced from character.

My apologies, as always, to those of you who did great work and aren’t on the list. I’m one person doing this on a shoestring, so plenty of outstanding writing escapes my attention or is gated beyond my sight. Normally I alphabetize the pieces by author surname, but some selections are grouped together by subject this year, so the entries appear in no particular order. Each selection is followed by my thoughts on the article and/or the subject.

Here, then, are 13,000 unedited words. What could possibly go wrong?

· · ·

1) “The Rise and Fall of Liz Smith, Celebrity Accomplice” (John Leland, New York Times)

Liz Smith was at the center of the culture, when the culture still had a center. Then the long tail of the Internet snapped her from the spotlight, as almost everyone became a celebrity and countless outlets allowed gossip to achieve ubiquity. The louche location of a newspaper no longer needed a name reporter any more than most blockbusters required a particular star. The pictures didn’t get smaller, but the people in them did. Like Walter Winchell, she outlived her fame.

No one deserved a steep decline more than Winchell, who Smith grew up listening to on radio when she was a girl in Texas in the Thirties. A figure of immense power in his heyday, Winchell was vicious and vindictive, often feared and seldom loved, the inspiration for the seedy and cynical J.J. Hunsecker in Sweet Smell of Success.

By the time journalism matured in the 1960s and college-educated industry professionals began saying “ellipsis” rather than “dot dot dot,” Winchell had no power left, and people were finally able to turn away from him—and turn they did. The former media massacrist was almost literally kicked to the curb, as Larry King recalls seeing the aged reporter standing on Los Angeles street corners handing out mimeographed copies of his no-longer-syndicated column. By the time he died in 1972, he was all but already buried, and his daughter was the lone mourner in attendance.

Smith was of a later generation, and unlike Winchell or Hedda Hopper, she usually served her information with a spoon rather than a knife—the scribe loved celebrity and access and privilege so much—though she occasionally eviscerated someone who behaved badly. Frank Sinatra was her most famous foe, and you had to respect her for not pulling punches based on the size of her opponent. In the 1980s, she was a major player. A decade later, as we entered the Internet Age and Reality TV era, her empire began to crumble. In 2017, at age 94, she wondered where it all went.

In one sense, Smith was like a lot of retirees pushed from a powerful perch. In another, because she worked in the media in a disruptive age, she had embedded in her the scars of a technological revolution that turned the page with no regard for the boldness of the bylines.

Leland expertly profiled the former power broker just four months before her death.•

· · ·

2) “The Power of Trump’s Positive Thinking” (Michael Kruse, Politico Magazine)

From Rev. Ike to Dr. Phil to Pres. Trump, America has embraced mountebanks of many types in religion and medicine and politics, asking only that they be skilled at satisfying our hunger to turn every last thing in the country into entertainment.

Norman Vincent Peale, a pastor and peddler of positivity, fit somewhere into that paradigm, offering a malleable feel-good philosophy that encouraged personal fulfillment over self-sacrifice, creating in the process the prototype for a narcissistic me-first faith that really took root during the 1970s and has never since retreated. It’s no wonder Donald Trump worshiped so devoutly at his altar. In fact, Peale presided over the serial groom’s first nuptials.

Oddly, the pastor spent the pre-WWII era worried that a demagogic faux populist would be elevated to the Oval Office, not realizing, of course, that one of his future parishioners would come closest to filling the bill. Despite his fear of American Fascism, it’s no sure thing that Peale would have been aghast at Trump’s ascent. The religious leader himself was known for some bigoted views and was deeply offended by the New Deal and any social programs aimed at mitigating the suffering of desperate Depression-ites. Was he so pliant that he could have twisted himself into a Trump supporter? No way of knowing, but he certainly played an important role, willingly or not, in the development of the Worst American™.

As Kruse ably demonstrates, Trump’s positivity long ago curdled into something pernicious.•

· · ·

3) “Inside the First Church of Artificial Intelligence“ (Mark Harris, Wired)

The implied religiosity which often attends Artificial Intelligence, a dynamic identified by Jaron Lanier among other technological critics, becomes explicit in the Way of the Future, roboticist Anthony Levandowski’s new Silicon Valley spiritual-belief system in which the Four Horsemen, should they arrive, will do so in driverless cars.

To be perfectly accurate, Levandowski, the pivotal figure in the current legal scrum between Google and Uber over autonomous-vehicle intellectual property, isn’t prophesying End of Days scenarios but is rather preaching that we are in the process of transitioning from a planet ruled by humans (not great guardians, admittedly) to one governed by what he thinks will be superior machines. If we get on our knees at his church today, he believes, we’ll be much more likely to be accepted tomorrow as docile pets by our new masters.

Techno-theocracy is nothing new, of course. During the disco-addled decade of the Seventies, such a religion was promoted by the computer-savvy, self-described messiah Maharaj Ji, a teenage guru from India who briefly came to prominence in America. From a 1974 profile of him by Marjoe Gortner:

The guru is much more technologically oriented, though. He spreads a lot of word and keeps tabs on who needs what through a very sophisticated Telex system that reaches out to all the communes or ashrams around the country. He can keep count of who needs how many T-shirts, pairs of socks–stuff like that. And his own people run this system; it’s free labor for the corporation.

The morning of the third day I was feeling blessed and refreshed, and I was looking forward to the guru’s plans for the Divine City, which was soon going to be built somewhere in the U. S. I wanted to hear what that was all about.

It was unbelievable. The city was to consist of “modular units adaptable to any desired shape.” The structures would have waste-recycling devices so that water could be drunk over and over. They even planned to have toothbrushes with handles you could squeeze to have the proper amount of paste pop up (the crowd was agog at this). There would be a computer in each communal house so that with just a touch of the hand you could check to see if a book you wanted was available, and if it was, it would be hand-messengered to you. A complete modern city of robots. I was thinking: whatever happened to mountains and waterfalls and streams and fresh air? This was going to be a technological, computerized nightmare! It repulsed me. Computer cards to buy essentials at a central storeroom! And no cheating, of course. If you flashed your card for an item you already had, the computer would reject it. The perfect turn-off. The spokesman for this city announced that the blueprints had already been drawn up and actual construction would be the next step. Controlled rain, light, and space. Bubble power! It was all beginning to be very frightening.

Harris composed a pair of pieces—read also: “God Is a Bot, and Anthony Levandowski Is His Messenger“—on the would-be Silicon Valley spiritualist, who, like many in the Singularity industry, worships at the altar of “intelligence,” a term far more slippery to define than many in the sector are willing to admit. The algorithmic abbot believes heretofore unimaginable machine IQ must equate to God. “If there is something a billion times smarter than the smartest human,” he says, “what else are you going to call it?” Well, perhaps the devil?•

· · ·

4) “The Strange Pleasure of Seeing Carter Page Set Himself on Fire” (Rick Wilson, Daily Beast)

In his wonderfully Hitchensesque hit job on black-market kidney peddler Carter Page, Wilson also tees off on dissolute Hitlerite Steve Bannon, describing him as “a man better suited to promoting bumfights than grand strategy.” While dunking on dotards won’t save the Republic, respect must still be paid to the most awesomely scathing piece I read all year.•

· · ·

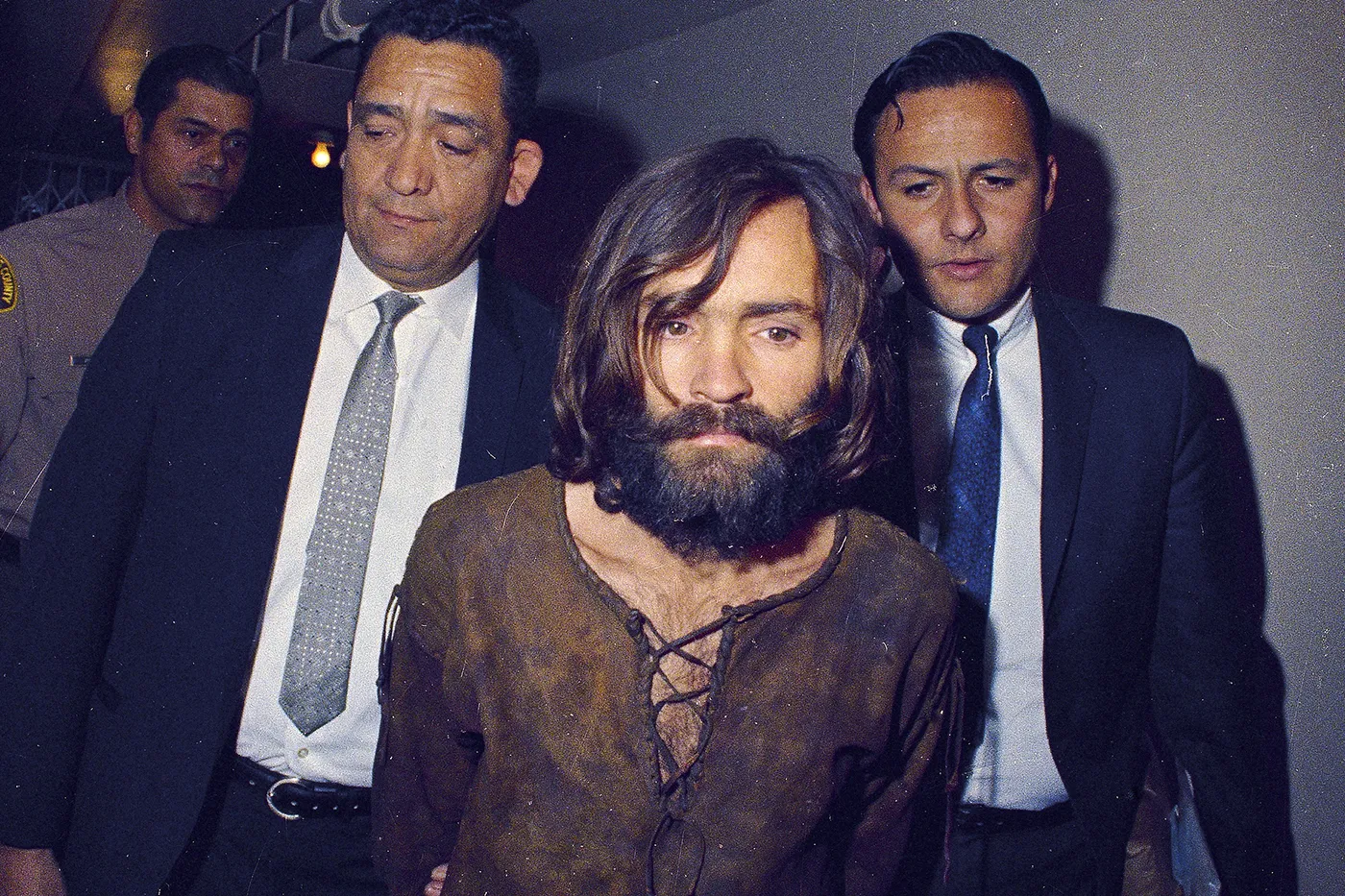

5) “Charles Manson’s Science Fiction Roots” (Jeet Heer, New Republic)

Manson’s long-anticipated dirt nap awakened a variety of disquieting thoughts, but only the febrile, idiosyncratic mind of Heer, the cultural critic and tireless Twitter wit, immediately did a deep dive on the connection between the creepy cultist and another pseudo-religious figure, explaining how the architect of the Tate-LaBianca murders was influenced by L. Ron Hubbard, the Sea Org Ahab who harpooned Hollywood.

Manson, who appropriately learned of Scientology during an early stretch in prison, was conditioned by his abusive childhood, drug use and delusions of grandeur to believe he would ignite a race-based World War III during the Sixties. His logic was absent but his timing exquisite, as California of that era was the rare milieu in which the predatory paterfamilias’ rat-faced rants didn’t initially stand out as exceedingly peculiar.

Manson soon proved himself a pathetic, murderous runt, though a uniquely American one with a Gump-like ability to cross paths during the open-door days of Los Angeles with celebrities from Dennis Wilson to Neil Young to Terry Melcher, the only son of Doris Day, the country’s immaculate mother. Once caged, he still managed to brush up against celebrities, making the acquaintance of Timothy Leary at Folsom in the 1970s. Manson was to some extent one of the last of the Western villains, truly infamous right before that description ceased being an insult.

In telling of Manson’s travels as a stranger in a strange land, Heer writes of perpetual-motion machines, telekinesis, Dianetics, Milton Friedman’s economics and other dubious expressions of the American imagination.•

· · ·

6) “The Nationalist’s Delusion” (Adam Serwer, Atlantic)

My favorite essay of the year, Serwer’s sharp, surgical take down of the received wisdom that “forgotten Americans” suffering from “economic anxiety” supported an orange supremacist like Donald Trump into the White House to send Washington a message. That plot line was abetted by sloppy reporting that repeatedly said Trump won the working-class vote, which is only true if you eliminate African-Americans from that category. And why, exactly, would you do that?

The writer provides historical context for his arguments, making a compelling case that recent disturbing occurrences like David Duke’s political rise and the bigotry of Birtherism were not isolated events but instead reminders that a wide swath of the nation was still carrying the torch of white supremacy. Sure, there are certainly a scary number of citizens struggling in the country’s extremely polarized financial reality, but Trump enjoyed support among the broad class spectrum of white voters, and interpreting his successful wooing of millions of Caucasians as anything other than cultural warfare is disingenuous. “He says what I’m thinking,” many of his ardent followers on the trail would offer, and considering what he was saying, the nature of the attraction was clear. Serwer methodically obliterates numerous lazy narratives hatched to explain away the obvious, credibly asserting that “had racism been toxic to the American electorate, Trump’s candidacy would not have been viable.”•

· · ·

7) “RT, Sputnik and Russia’s New Theory of War” (Jim Rutenberg, New York Times Magazine)

Jesse Ventura has decried how stupid Americans are, but without so many dummies, would he even have a career?

Pat Buchanan has been called the precursor to Trump because of their shared white nationalist platform, but Ventura is more precisely the current President’s political forefather despite being five years his junior. Like Trump, Ventura crawled from the wreckage of U.S. trash culture, pro wrestling and talk radio, to win a major public office (Minnesota governor) by utilizing off-center media tactics to portray himself as some sort of vague “outlaw truth-teller” while running against the “establishment.” He was an “anti-candidate” who made politics itself and the mainstream media his enemies, and the public got swept up in the rebellious facade of it all. His great joy in the process seemed to be that his upset victory, to borrow a phrase from Muhammad Ali, “shocked the world,” as if surprise and entertainment were the goals of politics and not actual good governance.

After a dismal term in office, Ventura bowed out of politics and fashioned some sort of career from crap TV (just like Trump), peddling asinine conspiracy theories (another thing he shares with Trump) and making appearances on Howard Stern’s radio show (yet one more similarity with Trump.) He did these things in part to make money but also because he’s an exhibitionist in need of a surfeit of attention. Sound familiar?

Now both men seem to have the same boss—an often-shirtless guy named Vladimir—as Trump suspiciously refuses to say a bad word about the adversarial nation that greatly helped his candidacy, and Ventura has decided to marry his egotistical horseshit to anti-Americanism on RT, Putin’s propaganda channel. The checks must be clearing because the fake wrestler announced on the inaugural episode of his new show that Russian interference in our election is fake news. “Where’s the proof?” Ventura asks. He’ll no doubt remain in a state of disbelief even should Robert Mueller provide copious documents and recordings. The murderous dictator that employs him will demand it.

Rutenberg’s report goes into the guts of the Kremlin propaganda machine, exploring how Putin is using Digital Age tools to reach across borders and into voting booths, rather than employing them to create a better tomorrow for Russia. As Bruce Sterling has written, “Technology is pursued not to accelerate progress but to intensify power.”•

· · ·

8) “Blade Runner’s Chillingly Prescient Vision of the Future,” (Marsha Gordon, The Conversation)

Even Disney devotee Ray Bradbury, who more than 50 years ago anxiously anticipated one fine day in the twenty-first century when Caesar would be “reborn” and again address the masses, this time via some sort of hologram, was leery about what might come to pass. “Am I frightened by any of this?” he asked. “Yes, certainly. For these audio-animatronic museums must be placed in hands that will build the truths as well as possible, and lie only through occasional error.”

Vision and speech recognition, cornerstones of Artificial Intelligence, will be utilized in a further assault on reality via generated media and other methods, should they fall into the wrong hands, which they will, of course, as they’ll be in all hands soon enough. A race for AI dominance among nations and corporations almost demands a boom in this sector. This means the veracity of everything from ancient history to the most recent trending topic will become even more muddled.

In an excellent essay about the meaning of the original Blade Runner prompted by the release of its sequel, Gordon wonders about the withering of memory in the presence of profound AI, as reality receives an “upgrade.”•

· · ·

9) “On the Milo Bus with the Lost Boys of America’s New Right” (Laurie Penny, Pacific·Standard)

Useful idiots hit the road when the Yiannopoulos yutzes rolled along with their pedophilia-approving British cult leader on an asinine tour of America during the latter stages of Trump’s equally ugly Presidential campaign. Unsurprisingly, these online provocateurs proved to be mice when too far from a mouse pad, cuck-calling cowards who threw tantrums when their taunts were returned. Penny’s compelling work reveals that though these walking dunce caps truly possess odious opinions in regards to race and gender, they weren’t nearly as invested in Trump actually becoming President as you might imagine. They mostly just wanted to break something on the outside because fixing the broken thing on the inside would require introspection, maturity and hard work. The journalist sums up the boys on the bus this way: “These are men, in short, who have founded an entire movement on the basis of refusing to handle their emotions like adults.”•

· · ·

10) “You Are the Product” (John Lanchester, London Review of Books)

Prior to dropping out of Harvard to turn Facebook into one of the most populous “states” on Earth, one that rivals even China, Mark Zuckerberg was a double major. One of those areas of study, unsurprisingly, was computer science. As Lanchester reminds in his excellent essay about the social network, the other concentration, psychology, is at least as vital in understanding how the entrepreneur was so successful in realizing the McLuhan nightmare of a Global Village well beyond what anyone else had been able to accomplish.

Zuckerberg didn’t really invent anything, as Friendster was already on the map. But his predecessor quickly faded while he’s developed the fastest growing service in the global history of business. His corporation’s amazing boom was and is driven primarily by three factors: The entrepreneur was at the right age to understand the trajectory of the market, he used his copious venture capital money to attract brilliant engineers and he purposely exploited a hole in our psyches. An Lanchester succinctly puts it: Zuckerberg had a keen understanding of the “social dynamics of popularity and status.”

That comprehension has permitted the company to “hire” a billion people to create free content for the platform each month, which would make Facebook by far the largest sweatshop in the annals of humanity, except even those dodgy operations pay some pittance. All you get for your efforts from Zuckerberg are “friends” and “likes,” which may be an even more lopsided return than receiving some strings of shiny beads in exchange for Manhattan.

The company might not have gone anywhere, however, had it not be for early seed money from Peter Thiel, the immigrant “genius” who was sure there were WMDs in Iraq and that Donald Trump would be a great President. What attracted the investor to the peculiar product was his reading of René Girard’s ideas on “mimesis,” which asserted that all human desires are borrowed from other people and we have an innate need to copy one another. The philosopher viewed this tendency as a human failing with sometimes grave consequences. Thiel, unburdened by a soul, saw it as an opportunity.

The blinding success of social media enriched Zuckerberg and Thiel, but is it good for individual users and society on a wider scale? This question is one the Facebook founder has probably never even entertained. His offspring can’t be a bad seed because he’s too deeply invested in it. Instead, after Facebook was deluged with criticism for its non-response to those who used the platform as a delivery system for Fake News during the 2016 Presidential election, Zuckerberg proposed a “solution” in his “Building Global Community” manifesto, one that essentially doubled down on the elements of his brand (extending connectedness and building “communities”) that are among the very problems. Certainly it benefits the company to downplay rather than neutralize Fake News, since Facebook, an advertising company, profits handsomely from such bullshit content.

Talk of a Zuckerberg run for the White House in 2020 has been all but silenced since the publication of Lanchester’s insightful, searing piece, as it’s clear he’s not even fully capable of running his virtual kingdom let alone a brick and mortar one. What seemed like an impenetrable fortress a year ago may now be stormed by regulators eager to do a job that Facebook (and Google and Twitter) either can’t or won’t do.•

· · ·

11) “Year One: My Anger Management” (Katha Pollitt, New York Review of Books)

The writer’s gloriously furious tirade vents about our country’s descent into the depths, which, although aided by the Kremlin machinations and FBI failings, was essentially a self-inflicted wound, one which feels like it could be a coup de grâce delivered to our own temple by nearly 63 million voters. The odious Trump cult, built upon the degeneration in American politics, media, education and finance, will end as sinister systems usually do, in some form of madness and death. Whether liberal governance itself is fatally wounded is still TBD.

· · ·

12) “The Digital Ruins of a Forgotten Future” (Leslie Jamison, Atlantic)

Ghost towns and other such abandoned plots are not only physical anymore but virtual as well, and soon enough the number of deceased will outnumber the living on Facebook and other social sites. In a fascinating, heady piece about the online virtual world Second Life a decade after most people left town, novelist and journalist Jamison looks at how another unintentional digital graveyard keeps its gates open, despite the once-popular hobby now mostly serving as a punchline. As the writer astutely notes, the derided and largely forgotten world of avatars is actually having the last laugh. That’s not only because plenty of people still find meaning in SL, often those hampered by disabilities and discrimination and dissatisfaction in the offline world, but because in a broader sense, the ideas of Philip Rosedale, the game’s creator, have conquered almost all of us. “If Second Life promised a future in which people would spend hours each day inhabiting their online identity,” she writes, “haven’t we found ourselves inside it? Only it’s come to pass on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter instead.”•

· · ·

13) “The First White President” (Ta-Nehisi Coates, Atlantic)

When my ancestors first arrived in America from Italy in the early decades of the twentieth century, they were not considered white. Even though each generation before me has been Italian-Americans married to other Italian-Americans, I am, in 2017, accepted as Caucasian. What changed?

It wasn’t skin color. I was welcomed into the race as a wedge against African-Americans securing a deserved place in the mainstream of U.S. life. Presently, in this nasty natavist period, Mexican-Americans are being rag-dolled by the Right, but is it impossible that in a few decades they too will have been awarded whiteness to further deny descendants of slaves? You can’t rule it out.

In an excerpt from We Were Eight Years in Power, Coates comments on a candidate who won the White House with not only the help of a murderous capo in the Kremlin but from a killer within, an angry mob that would surrender money, security, even democracy, to Make America Great White Again. In Trump they found an avenger with the zeal of a Klansman who believed it his mission to ensure the erasure from history of the first African-American President.

Am I as hopeless as Coates is about the U.S. getting race right someday? No, not usually, but let’s remember that I’m considered white, that nebulous and valued thing, at his expense.•

· · ·

14) “Oriana Fallaci, Right or Wrong” (Nina Burleigh, New York Times Book Review)

Fallaci was a merciless interrogator, though not a perfect one. Her hunter’s skills were used to perfection when cornering and toying with Henry Kissinger, who was beaten about the head by her paws until he acknowledged the complete uselessness of the Vietnam War. No, the former Nixon Secretary of State didn’t spend the bulk of his life in leg irons as he deserved, but there was this one deeply humiliating moment of comeuppance, which Kissinger later called “the single most disastrous conversation I have ever had with any member of the press.”

Fallaci was also prescient in her writing. During a 1960s interview with Hugh Hefner, she focused on his early adopting of isolating home technologies. He said to her: “I am in the center of the world, and I don’t need to go out looking for the world. The rational use that I make of progress and technology brings me the world at home. What distinguishes men from other animals? Is it not perhaps their capacity to control the environment and to change it according to their necessities and tastes? Many people will soon live as I do.”

Fallaci could sometimes be wide of the mark, like when she dubbed Alfred Hitchcock “Mr. Chastity” (Tippi Hedren begs to differ), or when she, in 1972, imagined Indira Gandhi a champion of justice. Three years later, Gandhi, rather than resign as Prime Minister after being convicted of election fraud, declared martial law, had her political opponents imprisoned and repealed many of the citizens’ freedoms. She had, in effect, become a dictator. Fallaci expressed bitter disappointment in her fallen idol. “I didn’t hide my regret and shame at having portrayed her in the past as a woman to love and respect,” she acknowledged. You could hardly blame Fallaci’s own devotees if they felt similarly jilted by the journalist’s own late-life fervency for Islamophobia, when the indefatigable stubbornness that had buoyed her for so long ultimately buried her in hatred.

In a review Christina de Stefano’s new Fallaci bio, Burleigh somehow manages in a little more than 1200 perfectly chosen words to capture the complexity and conflicts of a combustible career.•

· · ·

15) “The Most Famous ‘Undecided Voter’ Has Big Problems With Trump”

(Luke Mullins, CNN Politics)

Fuck Ken Bone and the culture he rode in on.

Shame on the Undecided doofus of the 2016 Presidential debates himself for failing to take advantage of the endless educational opportunities in the country, remaining a barely formed adult fetus with the brain power of a bottle cap. Even more shame on those among us who felt it necessary to turn the red-sweatered sluggard into a meme, because Americans need to make every last goddamn thing into entertainment, to manufacture moments to fill the desperately dreary lives we’ve fashioned for ourselves, even if this stupidity can get us all killed.

Fuck the media for its role in the same, not only for making Bone a supporting actor in a national tragedy but for featuring as its star a racist, ignorant game-show host, helping to legitimize someone who should have been too low and louche to cut the ribbon at the opening of a brand-spanking-new adult bookstore, let alone be allowed to stain the sheets in the Lincoln Bedroom. And fuck the media again for continuing this dangerous bullshit. Should Mark Cuban run for President? How about Alec Baldwin? Will the Rock enter the race? Why aim so high? This comment is made with all earnestness: Our leadership is presently so dumb and dishonest that even Kim Kardashian would do a better job than our sitting President. Kim Fucking Kardashian.

The Illinois insta-celeb has apparently taken his eyes off of hacked Fappening photos of Jennifer Lawrence long enough to realize that Donald Trump isn’t doing a uniformly stellar job as President. Perhaps the unnecessary suffering of Puerto Ricans and U.S. Virgin Islanders and refugees and immigrants and poor people and non-white folks and even the white dummies who voted for a Simon Cowell-ish strongman has finally reached the slow-on-the-uptake Bone? Who knows and who cares. More likely, he’s just moving his mouth-hole again, making ignorant noises at random, because noise, not news, is what rules in this immature, ill-informed nation.

While Bone deserves to be ushered from the stage in ignominy like a contestant who flubbed the very first question on Who Wants To Be a Millionaire?, Mullins’ article about the man who knew too little still manages to be an illuminating look at contemporary fame.•

· · ·

16) “The Painful Truth About Teeth” (Mary Jordan and Kevin Sullivan, Washington Post)

17) “A Death in Alabama Exposes the American Factory Dream” (Gary Silverman, Financial Times)

18) “To Understand Rising Inequality, Consider the Janitors at Two Top Companies, Then and Now” (Neil Irwin, New York Times)

Radical abundance, we’re told by Silicon Valley stalwarts, will soon be the product of 3D printers and other cool tools, making it possible for everyone to share in material wealth. That would be wonderful, except that we already have radical abundance, with more than enough resources to shelter, feed and educate everyone in the world. A fair distribution is what’s lacking, and the same may be true tomorrow since the problem with creating a more level playing field isn’t just ineptitude but also an active campaign by some to maintain the imbalance.

It’s long been said that Americans who were poor weren’t really poor, not like people in other less fortunate countries. Is that so? Wealth inequality has become a national crisis, and there are some fully employed citizens in 2017 who make ends meet by regularly selling their plasma. Few think twice about this situation, which is, of course, part of the problem.

Jordan and Sullivan provide a devastating account of rural Maryland denizens living off well water and unable to care for their tooth decay because of our societal rot. Silverman does his usual excellent reporting and analysis in explaining why factory jobs recently reshored aren’t what they used to be. Irwin illustrates exactly how U.S.-based corporations, which used to take some civic responsibility to raise all boats, now leaves those in the most tenuous circumstances to sink.•

· · ·

19) “Silicon Valley Is Turning Into Its Own Worst Fear” (Ted Chiang, BuzzFeed)

There are dual, deep-seated reasons, I think, for the modern preoccupation with apocalypse, which has never been more prevalent than it is currently in literature and art. Part of the fascination has to do with a fear that we’re placing ourselves in a watery grave in the Anthropocene, a completely understandable reaction to what we’ve wrought with climate change. We may, however, be just as worried that everything we’ve created won’t disappear, that we’ll never be free of our dissatisfaction with the techno-capitalistic surveillance society we’re increasingly engineering. Is there no way out?

Deep Learning is making strong, often mysterious moves, leading many to wonder whether our cleverness, once it’s beyond our control, will be the death of us. It would be a scene like one late in the original 1973 version of Westworld, in which one dejected scientist says resignedly about the robots run amok: “They’ve been designed by other computers…we don’t know exactly how they work.”

Perhaps, but the more realistic and pressing concern may be a hopelessly corrupt corporate state driven by powerful new tools that mine and sell our previously private data. This predicament is analyzed by fiction writer Chiang, who wonders if technologists fear remorseless AI with no concern for our well-being because it’s a “devil in their own image.”

It certainly does seem that as the computers have gotten smaller, so have our dreams. Technology isn’t nearly the only issue plaguing us, but it also isn’t the magical answer to our ills so many thought it would be. It more accurately seems to be exacerbating them, perhaps driving us to system failure.•

· · ·

20) “America’s Future Is Texas” (Lawrence Wright, New Yorker)

Former Governor Rick Perry may be the most perfect living embodiment of the dumb-as-dirt side of Texas, the kind of supremely confident stumblefuck you could imagine firing a corn dog and sucking on a pistol. Inexplicably appointed Secretary of Energy by an even more inexplicable President, the king of brain cramps made this bold statement at a West Virginia coal plant this year: “Here’s a little economics lesson—supply and demand. You put the supply out there and the demand will follow.”

That is definitely not how that thing works.

Perry is, of course, far from the looniest Longhorn to hold office, and it would all be fantastically colorful to outsiders were it not for the outsize influence the state’s ballooning population has on everything from textbooks to temperatures.

In a 2013 Time cover story “Why Texas is Our Future,” economist Tyler Cowen, whose Mercatus Center is bankrolled by the Koch brothers and who has shown himself to be “weak on crime” while this Administration attempts to steal our democracy, wondered if the Libertarian impulse of the state would spread throughout the country. I argued that California might be a more likely template, that Texas may not even be the future of Texas given its brisk population growth and changing demographics, though we won’t know for sure for awhile.

In making his argument, the economist hadn’t addressed numerous potential threats to his theory:

• Growing Mexican-American voting power goes unmentioned. It likely won’t help Republicans in that state or nationally in the near future.

• The politicians who favor the type of policies Cowen thinks are the future (little or no social safety net) are usually rejected at the ballot box. Trump won by running against his true intentions.

• You can’t assume that the influx of new citizens from disparate places to Texas won’t alter its political landscape. New arrivals may initially be attracted by no state income taxes, but they may grow weary of some of its less-appealing side effects.

• It’s hard to see how Texas’ seemingly endless cheap land could apply to most smaller American states. The supply just isn’t there. Zoning-law changes can help somewhat, but you can do just so much with so little.

• Vast stretches of Texas may be uninhabitable or, at the very least, far less inviting in a few decades, those oil wells doing their damage despite what the state’s elected climate-change deniers believe.

• It’s certainly not Cowen’s responsibility in predicting the future to skew his opinions to the more humanistic path, but I think he’s way too fatalistic about Americans accepting greater and greater income inequality. His view of the future is pretty chilling and it needn’t be realized. Sure, automation will become more prominent, but we do not have to politically allow our country to become an even more extreme version of haves and have-nots, adopting the policies of the state with the nation’s highest uninsured rate and an appalling poverty rate for women and girls.

Even beyond these obvious reasons that Texas today will likely not be America tomorrow is the simple fact that the state has been wildly gerrymandered by Republicans to distort the reality of its actual character, a process that has been duplicated across the country. Texas is purpler than it used to be, though still red, but much of its population runs up against its more backwards Jesus-rode-dinosaurs daffiness. Redistricting is a trick both parties have historically employed, and one that needs to end. The U.S. not truly and accurately represented is a Republic headed for disaster.

Wright, who spent most of his life living in the state and wrote for Texas Monthly, considers, as Cowen did, that the state may be a bellwether nationally—but does so from a very different perspective. The journalist’s headline implies Texas’ volatile, fractious politics, an “irrepressible conflict” writ even larger than we understand, may await us all.

While covering this year’s 140-day state-legislative session that played out like a dynamite factory visited by a wildfire, Wright provides an excellent tour through many of the historical and contemporary characters, policies and processes that make up the extreme politics of a state where it’s legal to shoot wild pigs from helicopters with machine guns. It’s more or less wartime reportage.

The combustible session often saw average conservatives trying to restrain the fringe-right ones, a group of white men aiming to build a wall around the future, which seems successful in the state at the moment, though it may actually be a death rattle from a population that’s been eclipsed.•

· · ·

21) “Tiny House Hunters and the Shrinking American Dream” (Roxane Gay, Curbed)

There’s nothing wrong with refusing to buy into our consumerist society, because for some, less truly is more. “Downsizing,” however, has always been a euphemistic cover for darker forces at play. The term was first coined in the 1970s to convince empty nesters they would die of loneliness if they continued residing in homes where they raised their children, as if having quiet time to contemplate inside of familiar walls was somehow strange and inappropriate. What’s more, it was considered almost selfish for older folks to continue taking up so much space. Make room for productive people.

The word’s been repurposed during this time of yawning wealth inequality to put a smiley emoji on the new normal of citizens being unable to afford reasonably sized homes (and hopes). The country can now be divided into those with millions and billions and the majority surviving paycheck to paycheck, flying by the seat of its pants with no landing strip in sight.

In her insightful essay about the Reality TV show in which Americans seem a little too gleeful about having to stuff their aspirations into a shoe box, brilliant author and cultural critic Gay considers the eye-popping price tag of what’s commonly considered the American Dream, which may be a bill of goods as well as unaffordable to most.•

· · ·

22) “A Likely Story,” (Mimi Kramer, Medium)

When Tina Brown was the Editor-in-Chief of the New Yorker, she would comment that “cuteness” was a factor in hiring writers. It seemed like more than a flippant remark. That was the world she wanted to inhabit, one in which appearance, in a number of ways, was preeminent. It’s a mindset that’s added little to the culture.

There were many changes the New Yorker needed to be make in 1992 when Brown was brought in to perform as a wrecking ball for the then-staid institution. Many of her reinventions weren’t the right ones, however. David Remnick often gives his predecessor credit for doing the heavy lifting in recreating the title, but female writers and editors (besides herself) were often pushed from the foreground on her watch. It’s only deep into Remnick’s reign that this egregious shift has been largely remedied. Hollywood and celebrity became central to the publication under Brown, and I will never forgive her for allowing Roseanne to guest edit an edition, the cheapest ploy in magazine’s history. (That’s no offense to Roseanne, an excellent comic, but to the Editor-in-Chief who put her in that ridiculous position.) In addition to paring down the staff of scribes who’d ceased being useful, Brown also drove out many great and productive writers.

It’s no shock Brown ended up in business with Harvey Weinstein—they were always on the same team. Funny, in retrospect, that Brown’s first cover featured a punk. Her punk phase was as genuine as Ivanka Trump’s.

In Kramer’s essay, the former New Yorker theater critic not only crafts one of the most intelligent pieces on shitty men in media and elsewhere but also excoriates Brown, her former boss, with unsparing precision.•

· · ·

23) “Your Animal Life Is Over. Machine Life Has Begun.” (Mark O’Connell, Guardian)

If we don’t kill ourselves first and we probably will, the Posthuman Industrial Complex will ultimately become a going concern. I can’t say I’m sorry I’ll miss out on it. Certainly establishing human colonies in space would change life or perhaps we’ll do so through engineering as a precursor to settling the final frontier. As Freeman Dyson wrote:

Sometime in the next few hundred years, biotechnology will have advanced to the point where we can design and breed entire ecologies of living creatures adapted to survive in remote places away from Earth. I give the name Noah’s Ark culture to this style of space operation. A Noah’s Ark spacecraft is an object about the size and weight of an ostrich egg, containing living seeds with the genetic instructions for growing millions of species of microbes and plants and animals, including males and females of sexual species, adapted to live together and support one another in an alien environment.

There are also computational scientists among the techno-progressivists who are endeavoring, with the financial aid of their deep-pocketed Silicon Valley investors, to radically alter life down here, believing biology itself a design flaw. To such people, there are many questions and technology is the default answer.

In an excellent excerpt from To Be a Machine, author Mark O’Connell explores the Transhumanisitic trend and its “profound metaphysical weirdness,” profiling the figures forging ahead with reverse brain engineering, neuroprostheses and emulations, who wish to reduce human beings to data.•

· · ·

24) “Growing Up in the Shadow of the Confederacy” (Vann R. Newkirk II, Atlantic)

Stone Mountain may as well have been Ground Zero for the Lost Cause, the systematic plan of the vanquished of the Civil War, led by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, to win the postbellum information war via a variety of revisionist media—statuary, textbooks, etc. In a break from the universal truism, the losers were allowed to write history, which is how Robert E. Lee was reinvented as an “honorable man” and violent treason perplexingly came to be known as a “noble effort.” This propaganda’s reverberations continue to this day, with White House Chief of Staff John Kelly recently giving voice to this dangerous distortion.

The mammoth Confederate monument carved into Georgia rock was originally begun by sculptor Gutzon Borglum, who was approached in 1915 by the UD of the C to fashion an unprecedented, larger-than-life tribute to the half-slave side of America. Make no mistake about what drove the endeavor: The initial model included a Ku Klux Klan altar, no surprise since the terrorist group was among the main financial backers of the vast artwork. Borglum was no doubt hired in part because of his great skill, but his deep nativist streak and KKK sympathies were also reasons for the offer and his acceptance of it. (He was ultimately fired from the project due to disputes with his bosses, and a succession of replacements saw it to conclusion over five decades. Borglum, of course, eventually created Mount Rushmore.)

What was writ large on Stone Mountain proliferated throughout the country, with more than 700 Confederate statues dotting small towns and big cities, even in Union states like Ohio. The Ku Klux Khakis descended on Charlottesville this past August to protest the removal of one such memorial, committing murder before the weekend was done.

Newkirk, a North Carolina native, recounts his experience growing up in an “occupied territory” in the shadows of one such monument, which loomed above him as a reminder and a threat. As he explains in his powerful article, disputing those who claim these are homages to heritage and not enduring symbols of supremacy, “stone men and iron horses are never built without purpose.”•

· · ·

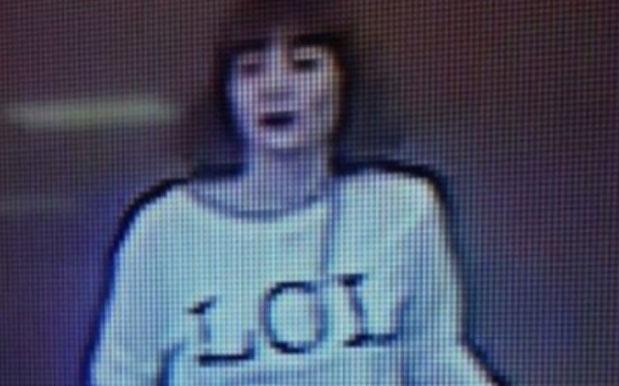

25) “The Untold Story of Kim Jong-nam’s Assassination” (Doug Bock Clark, GQ)

The Kardashians have, against all odds, stretched their 15 minutes of fame into a decade-long residency in a Warholian vomitorium, making a mint from their less-than-brilliant careers. Kris Jenner is a monstrous person who was happy to shamelessly sell her soul as well as her daughters to the highest bidder in exchange for some recognition and a string of shiny baubles. Even if she hadn’t been so good at her disgraceful line of work and they’d never managed to attract an unblinking spotlight to their famous-for-nothing act, they would have been a damaged brood drowning in their own tears. With that mother, they were doomed from the start.

The only important questions are what enabled the Kardashians to be famous, and why do so many people all over the globe wish for the kind of notoriety they possess? The first question is easier to answer. Two technological changes made the brand possible: A decentralized media allowed for an explosion of channels on TV and the Internet which created an overwhelming need for cheap content and new stars, and the advent of computer-based non-linear editing systems for video made such Reality fare technologically simple to piece together. The second query is more knotty. There is currently a hole inside us that makes many crave for attention beyond all satisfaction. The Kardashians may best represent that dynamic, but they are far from alone.

In Clark’s excellent exegesis of Kim Jong-nam’s Malaysian airport murder, he writes of how simple it was for North Korean agents to dupe fame-hungry young women into unwittingly committing murder with a nerve agent by convincing them they were merely participating in a hidden-camera Reality TV show. As shocking as the wetwork was—and it was deliberately so bizarre to send a chilling message to the world—you could hardly blame the clueless culprits for failing to recognize the ruse, not in a world of endless cameras and emotional cruelty, in which reality and fiction have become so blurred.•

· · ·

26) “What Happens If China Makes First Contact?” (Ross Andersen, The Atlantic)

Despite the millions poured into Harry Reid’s phantom UFO-detection program, citizens with their suspect saucer “sightings” have long given the search for extraterrestrial intelligence a bad name in America as assuredly as Timothy Leary made the potential medical benefits of LSD long unspeakable. But considering how much is out there—including stars like our sun and planets like our own—the odds are that we’re not alone.

China is set up to hear first if extraterrestrials make contact with humans any time in the foreseeable future, since that nation has invested most heavily in the technology necessary to enable such a meeting of the minds. Does it matter if a totalitarian regime is at the head of the line to greet the otherworldly? (That’s supposing, of course, that China remains autocratic.) Probably not, considering the Earth-shaking enormity of the event, one that would likely render any political designations meaningless. Of course, some probably felt the same about the original Space Race, and that didn’t turn out to be true, with numerous practical advantages subsequently enjoyed by America. But the realization of a close encounter with alien life would dwarf even boots on the moon.

Its realization of a village-clearing SETI telescope makes clear, however, that China is committed to science as America has taken a sharp turn from it, at least at our highest levels of government. If the autocratic state surpasses the U.S. and the rest of the planet in not only alien detection but also in solar panels, supercomputers, physics, etc., China would possess a soft power to go along with superior hardware, which would have a profound effect on world order. China’s dominance isn’t fait accompli, of course, as its poisonous dictatorial politics is a serious impediment to scientific growth. The valuable messiness of democracy may ultimately be a natural outgrowth of its continued development.

Andersen, a uniquely interesting writer and thinker, traces his trek to China’s premier SETI setup, home of the “world’s most sensitive telescope,” which looks like a caved-in Apple campus dotted with oil rigs, visiting along the way the novelist Liu Cixin and revisiting the populous state’s scientific history.•

· · ·

27) “Conservatism Can’t Survive Donald Trump Intact” (David Frum, Atlantic)

Erstwhile patriot and so-called Sensible Republican Lindsey Graham has thrown in with the traitorous Trump, so if he isn’t secretly working for the Mueller investigation, temporarily sacrificing his good name for the greater cause—not likely—either one of two possibilities is likely true: He’s being blackmailed over something personal, or he now realizes that the wide-ranging probe will also ensnare him, not an impossible outcome since he gladly pocketed Blavatnik money.

From the start, I’ve argued the GOP establishment probably wasn’t bolstering Trump because of tax cuts or Supreme Court seats (items more easily delivered by Mike Pence) but more likely due to the Kremlin’s tentacles reaching deeply into the party’s apparatus. The increasing attacks on Mueller by elected Republican officials and Fox News talkers suggest the same. Many aren’t endeavoring to save Trump but themselves.

If not only Trump is a turncoat but the entire party becomes identified as such, how will it recover should this inside job of a coup be put down? Frum, who’s done resolutely outstanding work during these troubled times, believes there’s no path back. The writer isn’t suggesting any party-wide wrongdoing as I have but is instead addressing how conservative thinkers have bent to the will of their putative leader and his most ardent adherents. The writer ultimately feels this ideology as it has been recently defined will not stay afloat in America after the crew’s pledge of allegiance to Trump, who’s both captain and mutineer.•

· · ·

28) “Chronicler of Islamic State ‘Killing Machine’ Goes Public” (Lori Hinnant and Maggie Michael, Associated Press)

Engrossing feature about Iraqi historian and blogger Omar Mohammed going undercover in Mosul to bear witness to IS atrocities, risking his own life to catalog an awful moment in time and give a name to both perpetrators and victims of monstrosity, even as he’d left his own identity behind. “Trust no one, document everything,” was the mantra of the “Mosul Eye,” as his readership—and the threat to his life—grew. Viewing beheadings and behandings eventually caused him to crack, but soon he was back on the beat, filling his spreadsheets and posts with accounts of torture and murder. Eventually, he bribed his way out of the country so that his documents wouldn’t disappear along with his life, continuing his journo-activism abroad from Turkey. A stunning act of bravery related brilliantly by Hinnant and Michael.•

· · ·

29) “Creating the Honest Man” (Kai Strittmatter, Süddeutsche Zeitung)

A terrifying report about the Chinese government’s attempt to build a ubiquitous surveillance state to quantify, judge and “guide” its citizens, using algorithms and facial recognition software to monitor everything from bill payments to bicycle rentals to blood donations, in order to “civilize people.” It’s an ungodly mix of behavioral science, technological overreach and totalitarianism. Right now this “Social Credit System” is just a voluntary app, but in a couple of years it will no longer be optional, and the process won’t just measure what nationals have done but will predict what they’ll next do. The measured will be divided into “good” and “bad” and rewarded and punished by an Office of Honesty’s computer calculations. As Strittmatter explains in his cogent article, it’s a “dictatorship that is reinventing itself digitally.”•

· · ·

30) “From Louis Armstrong to the N.F.L.: Ungrateful Is the New Uppity” (Jelani Cobb, New Yorker)

Certainly I wish Colin Kaepernick had voted in the Presidential election and encouraged others to do so, because no matter how disenfranchised you may feel in a system, you still live within it, as do many others who are more vulnerable than you, too young or old to fend for themselves. But there’s not much else this generous, civic-minded athlete hasn’t done right since he began sitting out the national anthem in 2016 to protest race-based police brutality, soon thereafter taking a knee to show respect to the flag even while refusing it his salute. From paying for business suits for recently released inmates to providing financial support to lower-income students, he’s a son of America of whom we should all be proud, even if he’s been called a “son of a bitch” by our most overtly racist President since Woodrow Wilson.

Cobb delves into the lexicon of oppression, recalling a time not so many decades ago when black Americans were deemed “uppity” if they didn’t go along with a program that defined them as less and questioned a system that favored their white counterparts. It was a term of admonishment but also a threat. Jack Johnson, who pulled no punches, was ruined because of his refusal to “know his role.” Even Louis Armstrong, who didn’t deliver knuckles to the nose but music to the ears, was castigated for his infrequent expressions of anger over the country’s unequal dynamic.

Kaepernick and other well-paid African-American athletes and entertainers who’ve made the stand for greater justice have recently begun being labeled “ungrateful,” which, of course, implies they should be thankful for all that they have because it’s only the largesse of white Americans that allows for such a thing. Trump, a Bull Connor of a condo salesman who made it to the White House on white-supremacist signalling, has unsurprisingly tried to turn a plea for fairness into a wedge issue. As Cobb eloquently explains, he is a “small man with a fetish for the symbols of democracy and a bottomless hostility for the actual practice of it.”•

· · ·

31) “Self-Taught Rocket Scientist Plans to Launch Over Ghost Town” (Pat Graham, Associated Press)

We tell ourselves stories in order to live, sure, but what if we tell the wrong ones?

Yes, there’s always been a strain of madness in American society, but the sideshow was ushered into the center ring in recent decades. The zealots, cranks and crooks have become the norm, or at least enough of the norm to tip the balance. Not that our country wasn’t sick before the Digital Age. Donald Trump’s rise, which began before Russian bots and Reality TV, perfectly traces our decline into system-crushing corruption. Now numerous erstwhile pillars of our nation shake and probably will fall. That will be messy, but it’s actually the best-case scenario: It’s still possible things remain standing and the fraudulent consume whatever justice remains.

Graham’s profile of a self-taught U.S. rocket scientist who believes the Earth is flat is a perfect metaphor for American exceptionalism run aground.•

· · ·

32) “Why Arendt Matters: Revisiting The Origins of Totalitarianism” (Roger Berkowitz, Los Angeles Review of Books)

What’s good for book publishers is not necessarily healthy for a society, which has been proven recently by Hannah Arendt’s work returning to fashion with a fury. According to her teachings on totalitarianism, Trump, despite his authoritarian aspirations, wouldn’t yet qualify as a despot, but as Berkowitz advises in his sobering essay, liberal governance can die by degrees.

Trump has relentlessly attacked institutions and mores as he continues to reinvent himself as something of an American Mussolini. Beyond besieging traditions, the system of checks and balances and the Fourth Estate, he has “shown a willingness to assert his personal control over reality,” as the writer asserts, offering to his faithful an alternative world that won’t, and can’t, be made manifest, but can serve as a safe haven from the truth.

When Berkowitz composed this piece in March, he wondered whether Trump would have to learn to exist within the Republican Party machinery in order to succeed. Instead, the GOP has shrunk itself to fit inside his pocket. The author suggests a return to the “Jeffersonian project of local self-government” to ward off the death of liberty, but such a shift won’t protect us in the present tense. Totalitarianism may be spoiled by Mueller or the masses or by the perpetrators’ sheer sloppiness, but it remains on the table. Nothing can truly shock anymore, a clear indicator of our deeply troubled situation.•

· · ·

33) “A Most American Terrorist: The Making of Dylann Roof” (Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, GQ)

American concerts, schools and even churches are no longer safe from terrorists, usually white men with guns. Ghansah brought a well-honed analytical eye, gorgeous writing skills and a profound psychological insight to one such horrifying case, turning out a remarkable account of a lone-wolf lynching bee, a strangely quiet 21-year-old man who entered a South Carolina church intending to kill as many black people as possible.

The writer digs beneath the easy narrative sold by monolithic media reports which depicted a congregation of endlessly forgiving African-Americans, revealing in the trial-coverage portion of her piece the deep well of rage against the unrepentant defendant, who appeared as a “young, demented monk with a tonsure.” Interviewing dozens of the defiant mass murderer’s relatives, teachers, classmates and coworkers, Ghansah succeeds in the challenging task of creating a portrait of a cipher of a man who committed an unspeakable crime—and the culture that produced him.•

· · ·

34) “What Putin Really Wants” (Julia Ioffe, Atlantic)

Vladimir Putin is stuck in the twentieth century, a dinosaur subsisting on old oil wells, guiding his nation toward existential risk as he settles for being a global troll rather than trying to remake his state to meet the challenges of a new millennium. That’s because he’s tremendously corrupt and not especially bright.

That his gambits aimed at destabilizing Western democracies have worked thus far is a clear indicator of societal decline in nations that embraced grifters selling Brexit and MAGA. Putin hasn’t pulled himself up as much as we’ve allowed ourselves to be lowered into his grave. He will ultimately be remembered, when he is dead or arrested, as anathema to sound governance, and one whose trail of personal evil likely extends much further than currently known.

Ioffe has steadily turned out outstanding work monitoring Kremlin intrigue, and in her best article of the year, she visits Russia to probe the computer culture that’s enabled Putin to seem omnipotent rather than the poseur he actually is, while analyzing the meaning of his attempts to hack history. It’s a complex tangle, and as the reporter writes: “Both Putin and his country are aging, declining—but the insecurities of decline present their own risks to America.”•

· · ·

35) “The Reclusive Hedge-Fund Tycoon Behind the Trump Presidency” (Jane Mayer, New Yorker)

36) “Robert Mercer, the Big Data Billionaire Waging War on Mainstream Media” (Carole Cadwalladr, Guardian)

There’s been an argument made by some economists (Libertarians, mostly) that if all Americans are growing richer it doesn’t matter if wealth inequality is ballooning. Two big problems: The all-boats-rising dynamic has been largely absent in recent decades, and even if money did move in such a manner, the vast resources held by a relative few would still allow them to exert undue influence on media, law and politics.

We witnessed such forces at work prior to the 2016 Presidential campaign when Peter Thiel shuttered Gawker by bankrolling the Hulk Hogan lawsuit, arguing it was righteous to do so because the blog was a “sociopathic bully.” That he soon thereafter began supporting a racist troll into the White House revealed a shocking level of hypocrisy. Thiel claimed that his attack on the media was a singular event, but Charles Harder, the lawyer who helped him kill Nick Denton’s company, began work on similar lawsuits.

In the political realm, the Kochs and the Mercers, who had long desired to force their .001% worldview on the country, became unfettered and largely inscrutable after the democracy-cracking Citizens United Supreme Court decision. Robert Mercer, along with the help of his daughter Rebekah, invested tens of millions in abetting fringe politics, conspiracy theories, Breitbart racism, Milo madness, Cambridge Analytica gaming and climate change denialism, when not busy playing with his $3 million Nile-sized toy train set. Mercer may be brilliant with computers, but he’s also a cuckoo with a choo-choo who believes nuclear war may be healthy and that the Civil Rights Act was a mistake. He will spend what it takes to miniaturize the government, reinvent it as an oligarchy or run the whole thing off the tracks, whichever comes first. His money is dark in more ways than one.

Mayer does her usual amazingly lucid work in breaking down how we arrived at this ignominious moment and explaining where it all may be heading. Cadwalladr continues to be invaluable for her effort to follow the money and make sense of the documents as she uncovers links connecting Mercer, Assange, Farage, Trump, Bannon and other suspect characters aiming to upend democracy.•

· · ·

37) “The Way Ahead” (Stephen Fry, stephenfry.com)

I’m given pause when someone compares the Internet to the printing press because the difference in degree between the inventions is astounding. For all the liberty Gutenberg’s machine brought to the printed word, you couldn’t slide one into your pocket, nor was it connected to billions of other such devices. It overwhelmingly put power into the hands of professionals, and while the eventual advent of copiers and other devices meant anyone could print anything, the vast majority of reading material produced was still overseen by gatekeepers (publishers, editors, etc.) who, on average, did the bidding of enlightenment.

By 1969, Glenn Gould believed the new technologies would allow for the sampling, remixing and democratization of creativity, that erstwhile members of the audience would ultimately ascend and become creators themselves. He hated the hierarchy of live performance and was sure its dominance would end. “The audiences [will] become the performer to a large extent,” he predicted. He couldn’t have known how right he was.

The Web has indeed brought us a greater degree of egalitarianism than we’ve ever possessed, as the centralization of media dissipated and the “fans” rushed the stage to put on a show of their own. Now here we all are crowded into the spotlight, a turn of events that’s been both blessing and curse. The utter democratization and the filter bubbles that have attended this phenomenon of endless channels have proven paradoxically (thus far) a threat to democracy. It’s acknowledged even by those who’ve been made billionaires by these new tools that “the Internet is the largest experiment involving anarchy in history,” though they never mention when some semblance of order might return.

In Fry’s excellent Hay Festival lecture, the writer and actor spoke on these same topics and other aspects of the Digital Age that are approaching with scary velocity. Like a lot of us, he was an instant convert to Web 1.0, charmed by what it delivered and awed by its staggering potential. Older, wiser and sadder for his knowledge of what’s come to pass, Fry tries to foresee what is next in a world in which social media cannot only help topple tyrants but can create them as well, knowing that the Internet of Things will only further complicate matters. Odds are life may be both greater and graver. He offers one word of advice: Prepare.•

· · ·

38) “Too Many Americans Live in a Mental Fog” (Noah Smith, Bloomberg View)

I’ve never felt nostalgic about “Mean Streets” New York, even if I don’t particularly like what’s replaced it, with runaway gentrification and a tourist-trap Times Square. When I was a child growing up in Queens during a rougher time in NYC history, incinerators spewed “black snow” over us when we played outside. The grade school I went to and apartment building we lived in were coated in asbestos until the city forced its removal. Usually really nice neighbors would stagger down the street completely drunk a couple times of week or get into fights when they were high, when they weren’t busy working or trying to care for their families.

These things come back to me sometimes. Like when I learned that fellow Queens native Stephen Jay Gould suffered from mesothelioma or when the news first broke that Flint children were essentially being raised on lead water or when the opioid crisis took hold.

In one of his best columns, Smith wonders about the silent costs of environmental problems, drug use and poverty. It’s a topic that’s discussed infrequently in the public realm since it’s easier (though costlier) to react to effects than causes. Occasionally someone will write an article about the far higher percentage of past traumatic brain injuries among convicts and wonder about causality, but that’s the exception. I’d love to read a study that traces the outcomes of those who play several years of tackle football in childhood against those who don’t.

Smith looks at the situation mostly from the economic costs of a brain-addled populace in the time when America has become chiefly an information culture, but successfully treating the foundational issues would relieve personal pain as well as better us broadly in a globally competitive business world.•

· · ·

39) “Departing AP Reporter Looks Back at Venezuela’s Slide” (Hannah Dreier, Associated Press)

Julian Assange was always a dubious character, but he probably didn’t begin his Wikileaks career as a Putin puppet. That’s what he’s become during this decade, however, helping the Kremlin tilt the 2016 U.S. Presidential election with coordinated leaks and serving in the post-election period as a defender of Donald Trump, as the Commander-in-Chief attempts to gradually degrade liberty and instill authoritarianism in America.

Assange’s most recent gambit was to warn of mass violence in the U.S.—encourage it, actually—by promising that the disaster unfolding in Venezuela would be replicated here should Trump be ousted from office for any number of nefarious acts that may be uncovered by Robert Mueller or other investigative officials. The analogy is dishonest since Venezuela’s decline is the result of gross mismanagement, not any political conflict. But large-scale civil unrest in America would be an ideal outcome for the Kremlin, which longs to destabilize the most powerful democracies.

Venezuela is going through a crazy-dangerous moment, for sure, and while the U.S. has a markedly different history and traditions, we could certainly will slide further toward such a nightmare if Trump and Assange get their way.

Dreier’s harrowing report reflects on her last days covering Venezuela’s fresh hell.•

· · ·

40) “Harvey Weinstein Paid Off Sexual Harassment Accusers for Decades” (Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, New York Times)

41) “From Aggressive Overtures to Sexual Assault: Harvey Weinstein’s Accusers Tell Their Stories” (Ronan Farrow, New Yorker)

Several of America’s most prominent institutions are simultaneously threatening collapse. That’s likely for the good, ultimately.

The gravest danger is in Washington, of course, where a Manchurian Russian candidate made his way to the White House with a Putin push and is sick enough to be willing to destroy democracy to save himself. A complicit, corrupt Republican Congress seems intent on allowing the Berlusconi who dreams of being a Mussolini to do just that. Only Robert Mueller’s team and tens of millions of citizens may be able to prevent such an outcome. One way or another, the whole thing is coming down and Trump will be covered in disgrace. The shape the rest of us will be in is TBD.

Janice Min is correct, I think, when she says it was a sexual predator like Donald Trump and his anti-women agenda landing in the Oval Office that caused Harvey Weinstein to finally be defenestrated from the penthouse. While that may have been the original impetus, the movement now has a life of its own. It was long overdue, and hopefully it’s only prelude.

As I wrote in the introduction, let’s remember it wasn’t an app hatched in Palo Alto that ended Weinstein’s monstrous behavior but rather the costly journalism turned out by a pair of legacy news organizations. Without this challenging reporting, all that’s become known in the aftermath would still remain undetected, undiagnosed, untreated.

In addition to the two articles listed above, also recommended are the follow-up pieces (“Weinstein’s Complicity Machine” by Kantor and Twohey again, along with Susan Dominus, Jim Rutenberg and Steve Eder; and Farrow’s chilling “Harvey Weinstein’s Army of Spies“). Stellar reporting and analysis were also done in this area by many others. To name just a few: Yashar Ali of Huffington Post, Rebecca Traister, Susan Fowler, Jia Tolentino and Emily Steel (the latter of whom documented some of the gross behavior at Vice, the American Apparel of journalism).

Most important of all, however, may have been Susan Chira and Catrin Einhorn’s NYT report on the harassment of women at Ford Motors. Most Americans don’t work in the so-called glamour industries, and it’s not as easy getting attention focused on abuses in blue-collar industries. No victory will be complete if reform fails to make its way from the opening credits to the end of the assembly line.•

· · ·

42) “The Secretive Family Making Billions From the Opioid Crisis” (Christopher Glazek, Esquire)

43) “The Family That Built an Empire of Pain” (Patrick Radden Keefe, New Yorker)

44) “Seven Days of Heroin” (Dan Horn and Terry DeMio, Cincinnati Enquirer)

The War on Drugs did not extend to the Sackler family, the dynastic dealers of opioids who’ve paid handsomely for the naming rights to galleries and gardens at A-list museums and universities, with billions they collected from poisoning the American well. It’s essentially blood money, the collection of which was enabled by a corrupt and sometimes naive medical industry, curious FDA decisions and a legal system that sent no one to prison despite felony convictions earned by numerous executives of the clan’s Purdue Pharma.

The pain-management business transformed the Sacklers in just over two decades from millionaires to billionaires, as they promoted OxyContin as less addictive than older-generation opioids. Always supremely careful with their reputation, the family has steadfastly kept their distance from the carnage they abetted, all but erasing their name from their outsize part in the pillification of America. The family has instead enjoyed admiration as it funneled some of its Oxy profits to Oxford University and other top-drawer institutions.

That cloak of invisibility has recently begun to be lifted by journalism, including a pair of stellar pieces of reporting this year by Glazek and Keefe, each of whom details the process behind the profits and lives lost to the scourge. “We were directed to lie,” one former Purdue sales rep tells Glazek. “Why mince words about it? Greed took hold and overruled everything.” As a recovering Long Island addict tells Keefe of his behavior after getting hooked: “I just created a hurricane of destruction.” The Sackler family has yet to be so honest about their role in the violent storm.

Focusing exclusively on the consumer side of the epidemic, Horn and DeMio and dozens of reporters, photographers and videographers combined to create a multimedia account of one week’s death and turmoil wrought by their region’s single greatest health crisis, putting a human face—many of them, actually—on a needless American tragedy.•

· · ·

45) “Trump’s Dictator Chic” (Peter York, Politico)

Fidel Castro attempted to hide his extravagant lifestyle, but he was an outlier among despots of recent vintage, most of whom have taken pains to cultivate conspicuous displays of wealth, which they believe projects unassailable power. It’s a sort of autocratic architecture, a weaponized interior design. Big, shiny hotel-esque hideousness was the preference of Nicolae Ceausescu, Saddam Hussein and Muammar Qaddafi, all of whom seemed to have uniformly possessed a child’s comprehension of what affluence should look like: a Vegas casino in which the house always wins.

The new millennia has continued with much of the same, though zeros have been added at the end of the number with rampant kleptocracies like the one in Russia, among other tyrannical regions of the globe. With the election of Donald Trump, a dictator whose tin pot is painted gold, the White House now has a figure given to ridiculous gaudiness, and his use of the Oval Office as a cash register for himself and his family is an unsurprising extension of this vulgar motif. It’s the prosperity gospel of mansionaires like the Osteens, adopted by a President who prays only for his own fortune.•

· · ·

46) “Woman Says Roy Moore Initiated Sexual Encounter When She Was 14, He Was 32” (Stephanie McCrummen, Beth Reinhard and Alice Crites, Washington Post)

Bold, dogged work by a trio of reporters and brave testimony by victims helped bring to heel, if just barely, the morally repugnant Alabama politician. Journalism can only do so much, however, even when its operating at its best as in this case. The rest depends on the citizenry. That a bigoted, theocratic, alleged child rapist came within a whisper of the Senate says something awful about the state we’re in. (That someone with many of these same terrible traits became President says the rest.) Those who voted for Moore knowing exactly what he is are heinous, but perhaps more dangerous are the supporters who didn’t accept what was obvious, choosing instead to live within a convenient delusion. A society that’s given up on objective reality in a large-scale way is doomed.•

· · ·

47) “The Hollywood Exec and the Hand Transplant That Changed His Life” (Amy Wallace, Los Angeles Magazine)

A gripping tale about a hale Hollywood exec who mysteriously suffers septic shock, somehow survives what should have killed him, loses at least part of all his limbs in the aftermath and undergoes a remarkably complicated and seldom attempted surgery. A nerve-wracking medical drama and inspirational story that Wallace expertly relates with the touch of a sportswriter.•

· · ·

48) “John Boehner Unchained” (Tim Alberta, Politico)

It’s an American tradition to rehabilitate political crooks, clods and liars of years gone by who are no longer in possession of power to do grave damage, which can make them seem harmless in retrospect. Kissinger is identified by many as wise statesman rather than mass murderer; Goldwater, the architect of society-busting Reagonomics, was the kindly man who shared anecdotes with Jay Leno in the 1990s; and George W. Bush is now an interesting outsider artist, not the guy who broke the world through incompetence and dishonesty. Forgiving is one thing, forgetting another.

The same tendency is currently at play with John Boehner, the weepy and often destructive former Speaker, who in his retirement is willing to say shitty things about shitty Republicans in between Marlboro drags and coughing fits. Some in the media and populace applaud because he was never as bad as Trump, but let’s recall that he was one of the agents who led to our current calamity.

Alberta’s fascinating piece is a portrait of Boehner at rest (or as close to it as he can manage).•

· · ·

49) “A History of the Future: How Writers Envisioned Tomorrow’s World” (John Gray, New Statesmen)

The Austrian physiologist Eugen Steinbach began researching “reactivation,” his term for the process of making the aged young all over again, in the 1890s. He promoted the use of “brain extracts” for all and developed for men a type of vasectomy that would allegedly repurpose semen into an internal youth serum. It was bollocks, but the procedure still helped the doctor gain fame—if not the approval of his medical peers—because people rightfully fear death, a hideous and permanent condition. A 1941 report in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle marveled at how the octogenarian, yet seemingly ageless, Steinbach was to go horseback riding on his birthday. What a remarkable specimen he’d turned himself into! He croaked three years later, however, like a mere commoner who’d been unenlightened about the bold ideas of educated men.

Today Alphabet aims to “cure death,” Libertarian putz Peter Thiel has vowed that HGH injections and other high-priced treatments will allow him to live to 140 (god help us all if so) and Singulatarian Ray Kurzweil pursues immortality by downing handfuls of supplements daily and trying to upload his brain into computers. Let’s hope for his sake it doesn’t wind up housed in Google Docs.

Don DeLillo’s 2016 novel, Zero K, takes on this fervor among the super-rich for an endless tomorrow: “We are born without choosing to be,” a character says. “Should we have to die in the same manner?” Well, we should search for better cures and longer lives, but there’s something creepy about the over-promising and narcissism of contemporary Silicon Valley immortalists who hope to escape societal collapse by fleeing to New Zealand and to outrun the Reaper through a combination of chemistry and computers. They talk about wanting to rescue the world, but they mostly want to save their own asses and stock options.

In Gray’s mixed review of Peter J. Bowler’s book about the hopes and fears provoked by what passes for progress, the philosopher examines the longstanding anti-death movement through Steinbach, Serge Voronoff and other historical crackpots, and interprets more technological utopias and dystopias that have sprung from laboratories and the humanities to fill our dreams and haunt our nightmares.•

· · ·

50) “Will We Have a Civil War?” (Keith Mines, Foreign Policy)