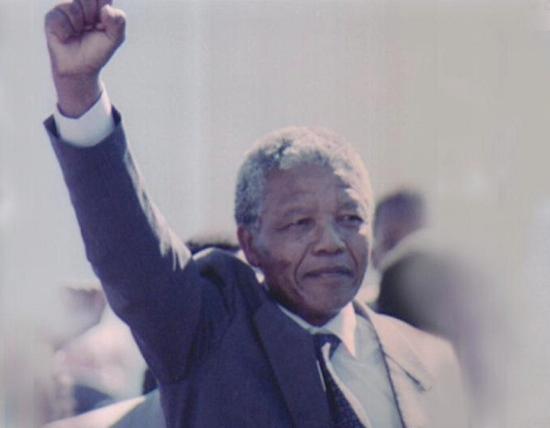

In a post at Practical Ethics, Dominic Wilkinson asks a thorny question that seems like a simple one at first blush: Should some people, who are considered exceptional, receive health care that others don’t? Of course not, we all would say. Human lives are equal in importance, and our loved ones are just as valuable as the most famous or successful among us. But Wilkinson quickly points out that Nelson Mandela, probably the most beloved among us during his life, received expensive and specialized care that would have been denied almost anyone else in South Africa. But how could we deny Mandela anything, after he sacrificed everything and ultimately led a nation 180 degrees from a civil war that could have cost countless lives? You can’t, really, though I would wager that Peter Singer disagrees with me. The opening of Wilkinson’s post:

“There are approximately 150,000 human deaths each day around the world. Most of those deaths pass without much notice, yet in the last ten days one death has received enormous, perhaps unprecedented, attention. The death and funeral of Nelson Mandela have been accompanied by countless pages of newsprint and hours of radio and television coverage. Much has been made of what was, by any account, an extraordinary life. There has been less attention, though, on Mandela’s last months and days. One uncomfortable question has not been asked. Was it ethical for this exceptional individual to receive treatment that would be denied to almost everyone else?

At the age of almost 95, and physically frail, Mandela was admitted to a South African hospital intensive care unit with pneumonia. He remained there for three months before being transferred for ongoing intensive care in a converted room in his own home. Although there are limited details available from media coverage it appears that Mandela received in his last six months a very large amount of highly expensive and invasive medical treatment. It was reported that he was receiving ventilation (breathing machine support) and renal dialysis (kidney machine). This level of treatment would be unthinkable for the vast majority of South Africans, and, indeed, the overwhelming majority of the people with similar illnesses even in developed countries. Frail elderly patients with pneumonia are not usually admitted to intensive care units. They do not have the option of prolonged support with breathing machines and dialysis at home.”