On the face of it, the Multiverse seems so very sci-fi-ish, but common sense tells us how unlikely it is that life on Earth turned out how it has. If there were trillions upon trillions of chances humans with smartphones and lattes would result, that would be more plausible. Natalie Wolchover and Peter Byrne’s Quanta article looks at the growing acceptance of the many-universe theory and the difficulties in making measure of it. The opening:

“If modern physics is to be believed, we shouldn’t be here. The meager dose of energy infusing empty space, which at higher levels would rip the cosmos apart, is a trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion times tinier than theory predicts. And the minuscule mass of the Higgs boson, whose relative smallness allows big structures such as galaxies and humans to form, falls roughly 100 quadrillion times short of expectations. Dialing up either of these constants even a little would render the universe unlivable.

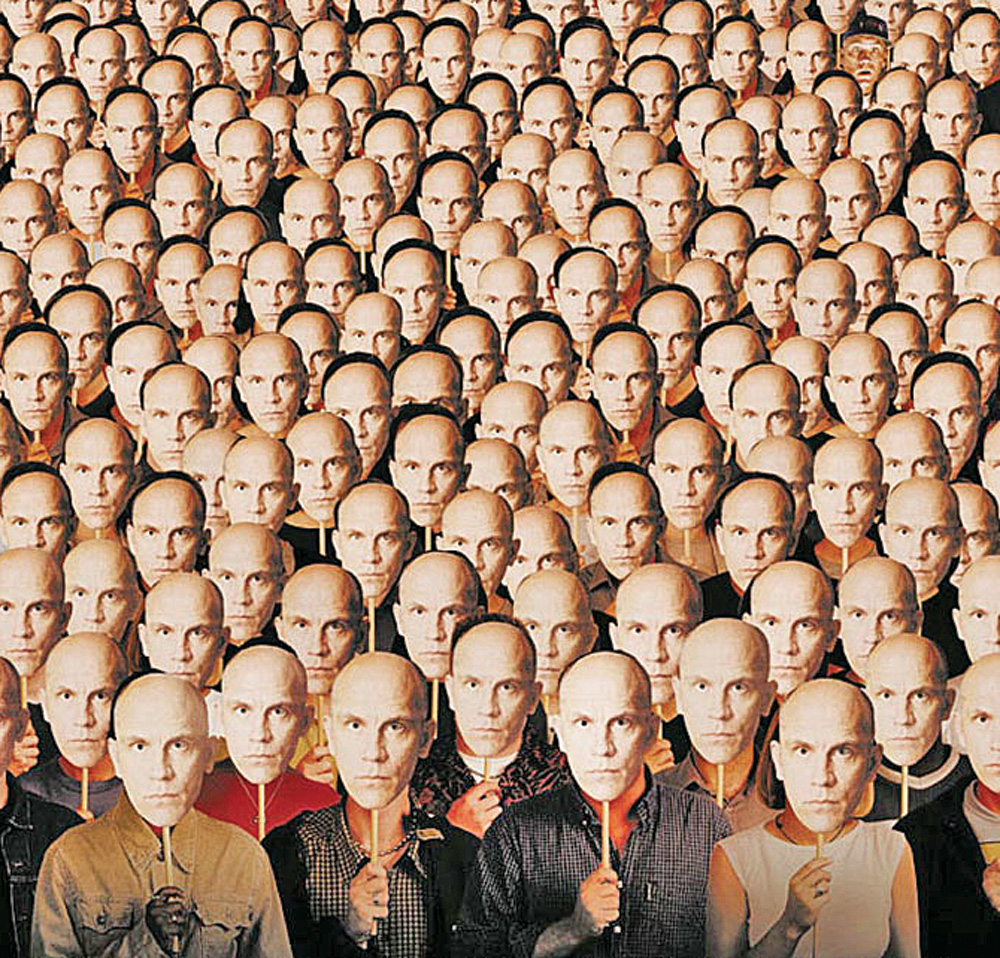

To account for our incredible luck, leading cosmologists like Alan Guth and Stephen Hawking envision our universe as one of countless bubbles in an eternally frothing sea. This infinite ‘multiverse’ would contain universes with constants tuned to any and all possible values, including some outliers, like ours, that have just the right properties to support life. In this scenario, our good luck is inevitable: A peculiar, life-friendly bubble is all we could expect to observe.

Many physicists loathe the multivere hypothesis, deeming it a cop-out of infinite proportions. But as attempts to paint our universe as an inevitable, self-contained structure falter, the multiverse camp is growing.

The problem remains how to test the hypothesis.”