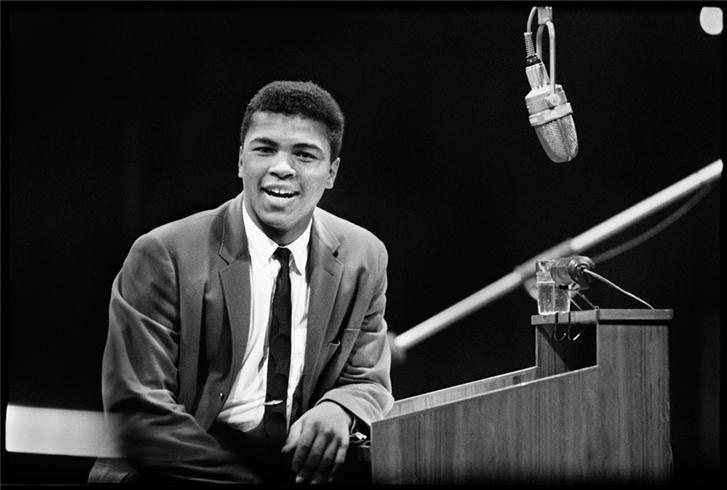

Muhammad Ali in 1972, after losing the “Fight of the Century” to Joe Frazier, on an Irish chat show hosted by Cathal O’Shannon. In Dublin to fight Alvin “Blue” Lewis, Ali was his usual mix of joking braggadocio and serious politics.

You are currently browsing articles tagged Muhammad Ali.

Tags: Cathal O'Shannon, Muhammad Ali

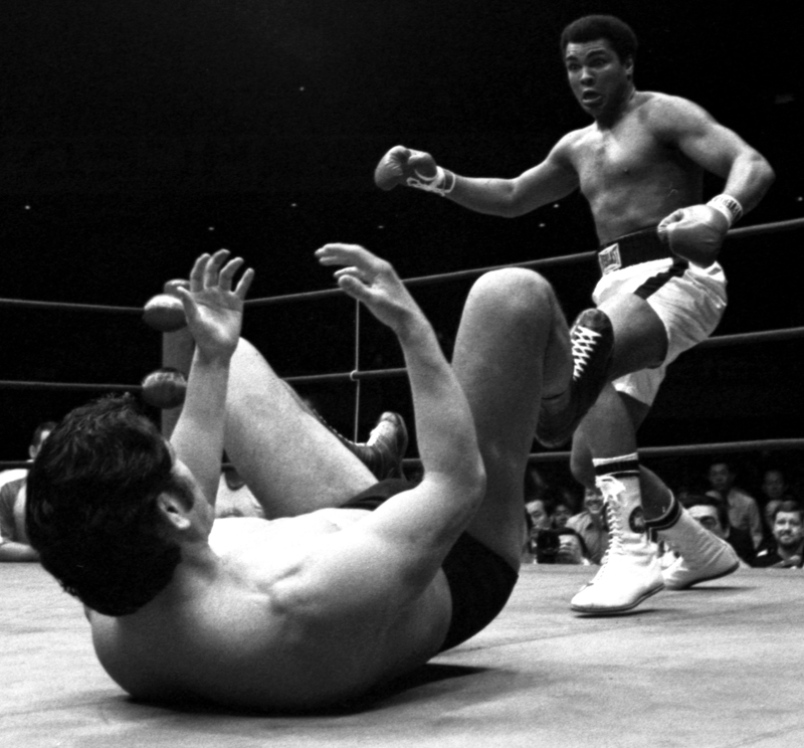

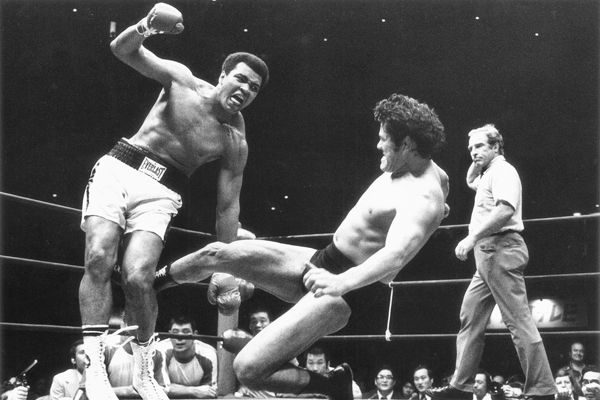

I’ve already posted the video of the “fight” between Muhammad Ali and Rocky Marciano, which was filmed scenes of the two then-undefeated heavyweight champions (the latter a long-retired one) with a computer supposedly scientifically deciding the winner. Ali needed a paycheck while living in exile in his own country during his military holdout, and Marciano wanted one more glow of warmth from the spotlight. It was to be his very last hurrah, as it turned out, as the older fighter died in a plane crash soon after the filming concluded. The sadness over his sudden death, the antipathy by some toward Ali during the Vietnam War, and the race of those feeding “expertise” into the computers, probably gave Marciano the hypothetical victory more than science did. In both boxers’ primes, I think Ali would have won convincingly. Here’s the brief copy from a 1970 Life magazine article that ran with photos from the film the week after it played in theaters:

“The only two heavyweight champions who never lost a professional fight are Rocky Marciano and Cassius (Muhammad Ali) Clay, and this has provoked many a nonprofessional fight among their fans. So Miami Promoter Murray Woroner decided to make a hypothetical ‘Super Fight’ of it, using a computer. First he matched the two champions and filmed 75 rounds of Hollywood-style fighting, finishing three weeks before Marciano’s death in a plane crash last summer. Then the skills and weaknesses of each fighter–as diagnosed by 1,500 sportswriters, fighters and managers–were programmed. The computer punched out a blow-by-blow reading and selected film segments were matched to it.

Seven possible endings were shot: a knockout, TKO and decisions for each man, and a draw. To foil any gambling capers, the seven endings were held in bonded secrecy until the last minute. When the film was shown at 750 theaters and arenas around the country last week, the result was dramatically uncomputerlike. Cut to simulated ribbons and even floored once, Marciano came back to knock Clay out in the 13th round. ‘It takes a good champion to lose like that,’ Clay smiled afterwards.”

Tags: Muhammad Ali, Murray Woroner, Rocky Marciano

In 1976, when he was already showing the early, subtle signs of Parkinson’s Syndrome, Muhammad Ali sat for a wide-ranging group interview on Face the Nation, in which he was mostly treated as a suspect by a panel of people who enjoyed privileges that were never available to the boxer. Fred Graham, the Arkansas-born correspondent who’s distinguished himself in other ways during his career, doesn’t come across as the most enlightened fellow here. Ali is even ridiculously criticized for a planned “bout” against Japanese wrestler Antonio Inoki.

Tags: Antonio Inoki, Fred Graham, Muhammad Ali

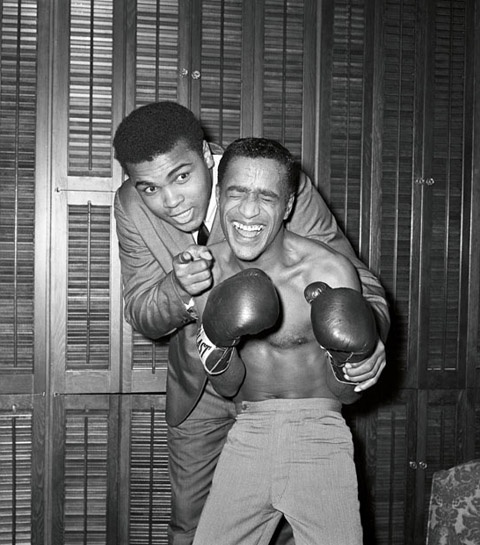

While subbing for Mike Douglas in 1970, Sammy Davis Jr., going through one of his phases, discusses Black Separatism and such with dethroned but undefeated boxing champ Muhammad Ali during his Vietnam Era walkabout.

Tags: Muhammad Ali, Sammy Davis Jr.

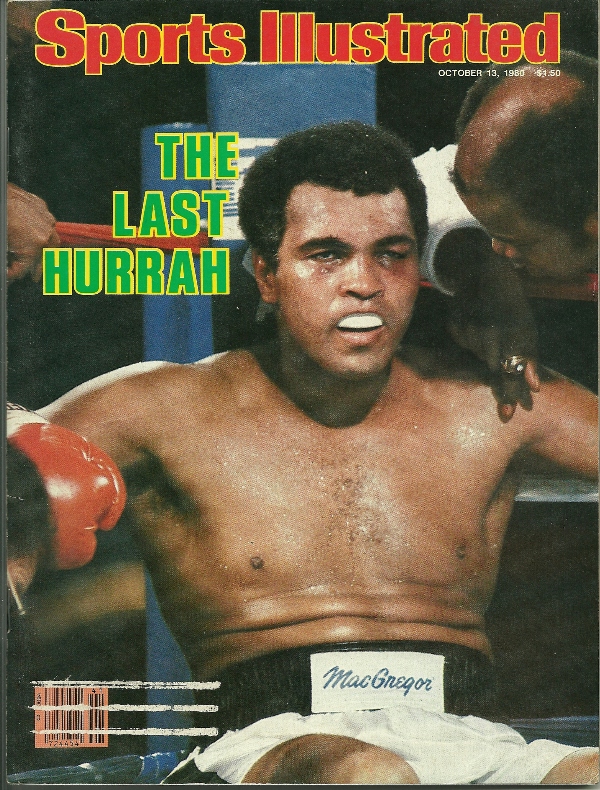

Muhammad Ali, jaw wired shut after having it broken by Ken Norton in just his second professional defeat, still managing to talk to Dick Cavett in 1973. He looks sad and shaken here and apparently considered retiring. Ali wouldn’t be quite the same sports legend if he hadn’t continued his career and fought Frazier twice more and Foreman once, but he’d not have suffered nearly the same neurological damage. By the time Ali boxed Larry Holmes in 1980, it was criminal he was allowed in the ring, his sad fate sealed.

Tags: Dick Cavett, Ken Norton, Muhammad Ali

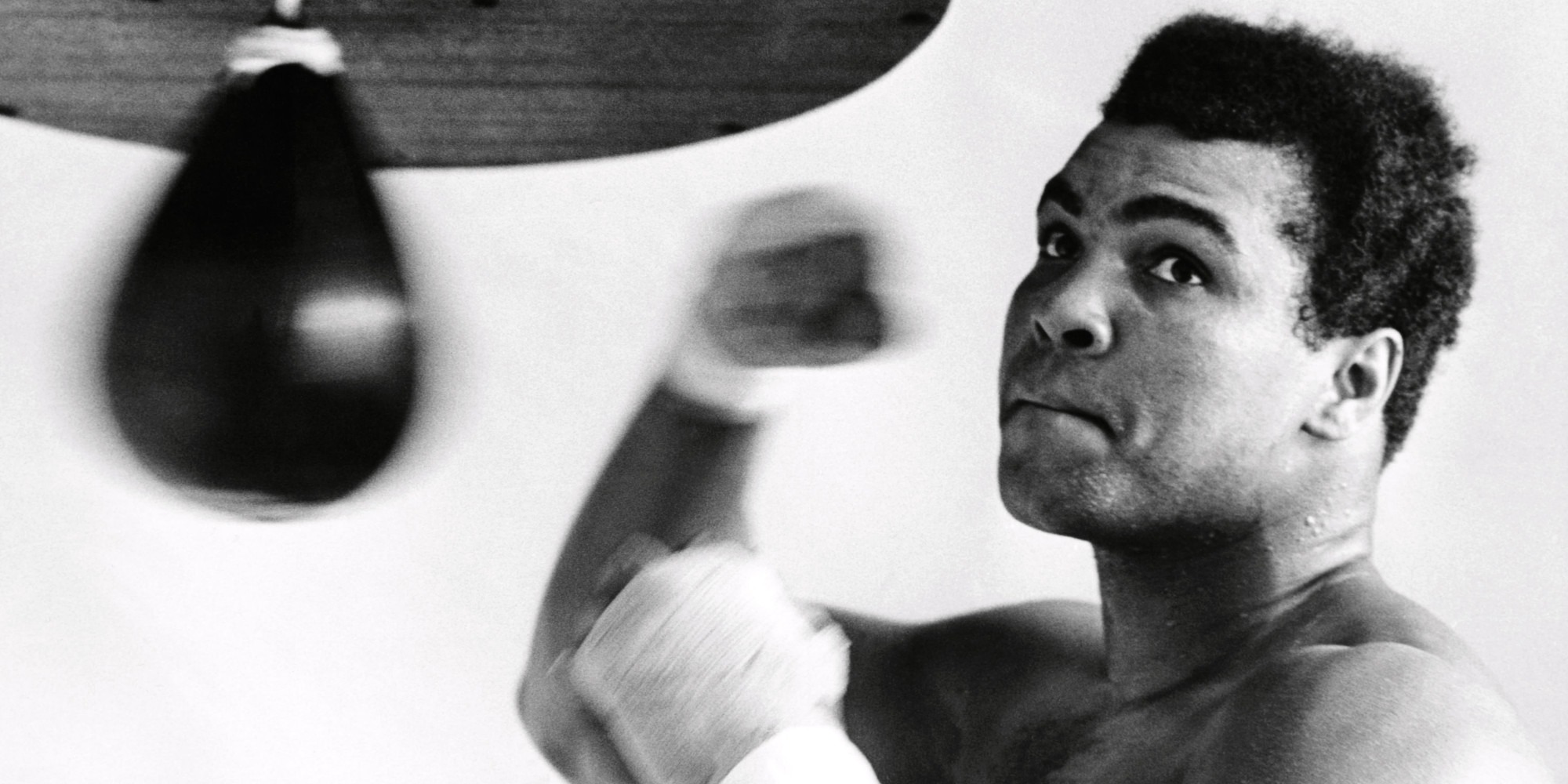

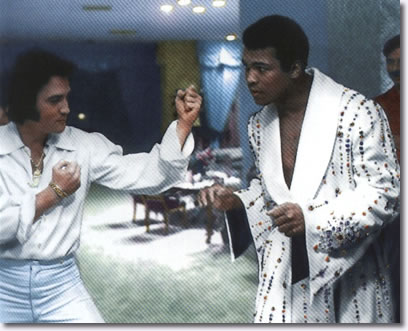

Muhammad Ali and Clint Eastwood hitting the speed bag for David Frost in 1970. Ali, who was in the midst of his Vietnam Era walkabout, was correct in saying that athletes from earlier periods weren’t as good as the ones of his generation, which wasn’t likely the conventional wisdom at the time.

Tags: Clint Eastwood, David Frost, Muhammad Ali

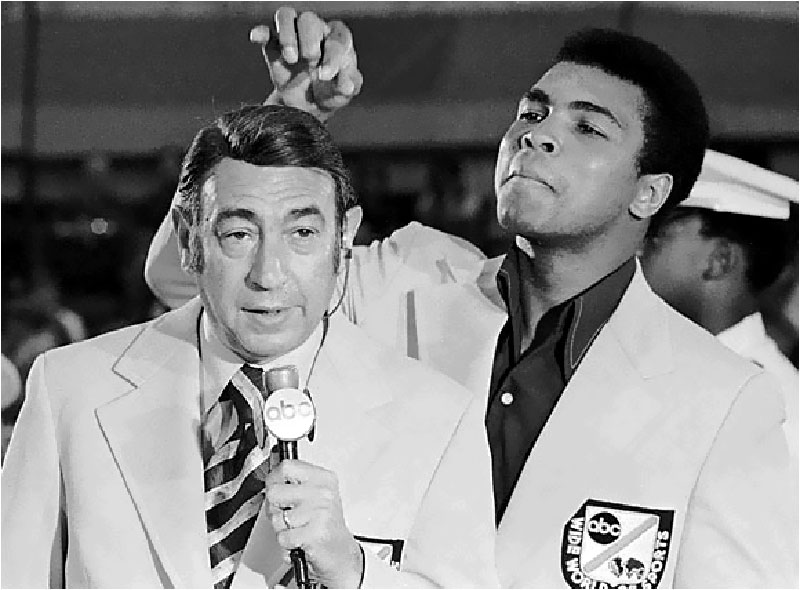

Howard Cosell guest hosts for Mike Douglas in 1972, welcoming (and baiting) his old sparring partner Muhammad Ali. The year prior, the boxer had lost for the first time in his career, to Joe Frazier in the so-called “Fight of the Century,” which is considered by some to be the greatest night in NYC history.

Tags: Howard Cosell, Joe Frazier, Muhammad Ali

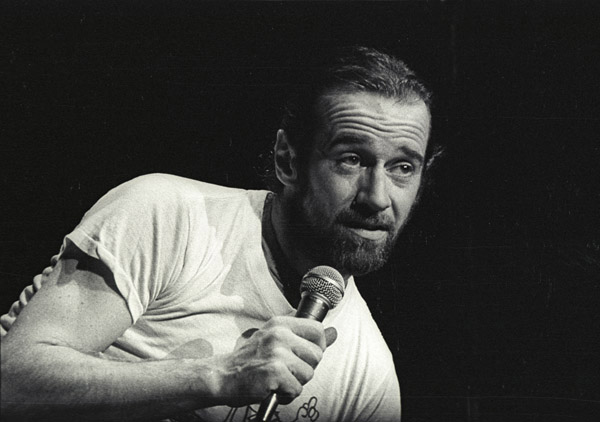

George Carlin on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1971, perfectly explicating the illogical reasoning behind Muhammad Ali’s forced Vietnam Era exile, as the fighter prepared for his first bout with Joe Frazier. Carlin’s performance was broadcast during the final few months of Sullivan’s 23-year run on CBS.

Tags: Ed Sullivan, George Carlin, Muhammad Ali

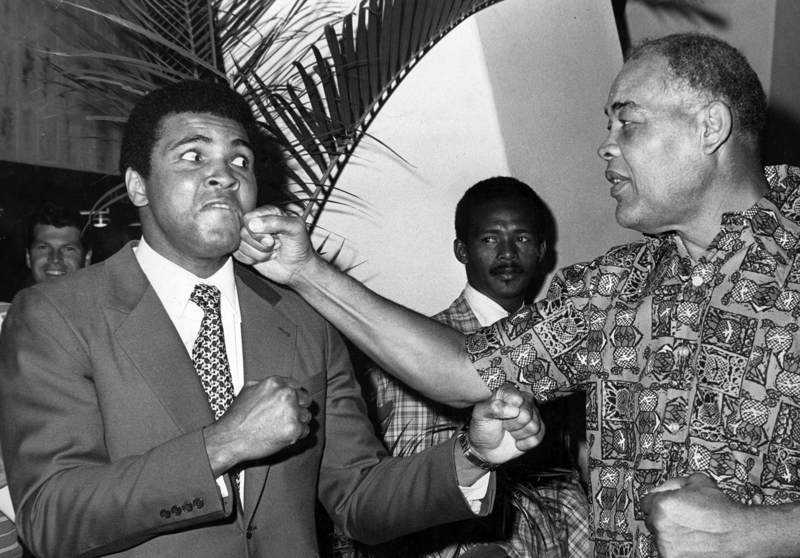

Muhammad Ali and Joe Louis seldom had a good word for each other–“Slow Joe Louis” was one of the nicer things Ali called his predecessor—and it wasn’t just joking. Louis picked Sonny Liston to win both Ali-Liston fights, and Ali never really forgave him. Louis seemed to be jealous of the brash younger fighter who was set to eclipse him.

This 1966 clip captures the two heavyweight egos when the men were actually working together briefly, with Louis acting in an adviser capacity. But Ali’s stance on the Vietnam war, among other issues, soon led to a bitter falling out.

Tags: Joe Louis, Muhammad Ali

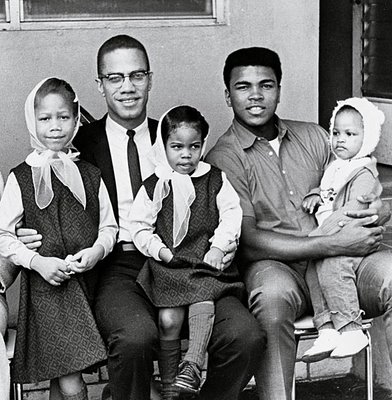

In this 1965 TV meeting with female members of the press, Muhammad Ali discusses Malcolm X’s estrangement from Elijah Muhammad’s brand of Islam. That means it had to have been recorded somewhere from January 1 to February 20 because the minister and activist was murdered on February 21 of that year.

Tags: Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali

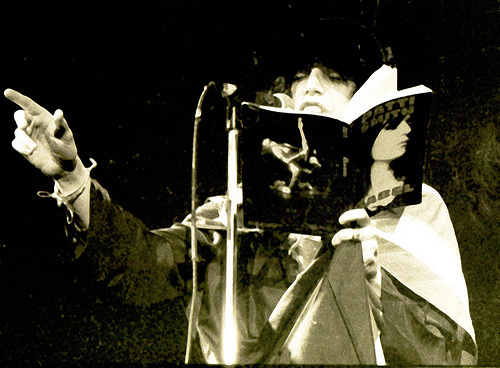

Patti Smith in 1978 visiting Mike Douglas to allegedly promote her book, Babel. Mike doesn’t approve of her looks. She didn’t have to put up with that crap in Penthouse. The host and guest surprisingly spend time discussing Muhammad Ali losing to Leon Spinks. Smith was apparently friends with Ali.

Tags: Leon Spinks, Mike Douglas, Muhammad Ali, Patti Smith

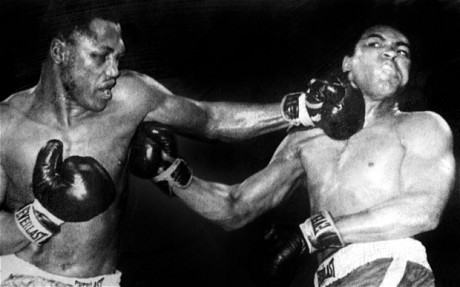

I’m firmly in the camp that believes Muhammad Ali legitimately beat Sonny Liston twice. The second fight, in 1965, caused so much consternation because Ali scored his knockout on a so-called “phantom punch” (which was actually an anchor punch). Howard Cosell corralled Jack Dempsey, Rocky Marciano, and journalists Jimmy Cannon and W.C. Heinz to discuss the controversy.

Postscript: Marciano “fought” Ali four years later via computer, right before perishing in a plane crash. In 1968, Heinz co-wrote the novel M*A*S*H under the pseudonym “Richard Hooker.”

Tags: Howard Cosell, Jack Dempsey, Jimmy Cannon, Muhammad Ali, Rocky Marciano, Sonny Liston, W.C. Heinz

When Muhammad Ali was asked where he got his great and playfully arrogant interview skills, he frequently credited seeing a clip of Gorgeous George, the wrestler who gained national fame in he 1950s as a narcissistic TV presence. Years later, it’s said that Ali realized that the one who had actually influenced him was another blonde grappler, Freddie Blassie. He had gotten them confused. In this 1976 clip, Tonight Show guest host McLean Stevenson and Ed McMahon welcome Ali and Blassie as the two hyped a mixed boxing-wrestling match featuring the Greatest versus Japanese wrestler Antonio Inoki.

Postscript: In 1990, Inoki, who had entered politics the year prior, was sent to Iraq to negotiate with Saddam Hussein for the release of Japanese hostages. Inoki secured their passage and converted to Islam later that year (Muslim name: Muhammad Hussain). He’s since had a contentious career in politics, even being elected to a seat in Japan’s Upper House.

Tags: Antonio Inoki, Ed McMahon, McLean Stevenson, Muhammad Ali, Saddam Hussein

Tags: Muhammad Ali, Nikki Giovanni

Muhammad Ali visits with Dick Cavett in 1978 in the wake of his loss to Leon Spinks. Ali, now slowed and beloved, would win a rematch in his final great moment as a boxer, but he really, really should have been retired for several years at this point.

Tags: Dick Cavett, Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali came close to boxing the ears of Joe Namath during a 1969 installment of the talk show hosted by the Jets quarterback. This was during the period when the boxer when the boxer had been stripped of the heavyweight championship for refusing to serve in the U.S. military, and he was in no mood. Oh, and George Segal and his facial hair dropped by.

Tags: Dick Schapp, George Segal, Joe Namath, Muhammad Ali

Wilt Chamberlain was a remarkable athlete (basketball, volleyball, track and field), but it’s probably a good thing he never realized his dream to fight Muhammad Ali. Howard Cosell presides over the ridiculousness, as he often did.

From East Side Boxing: “Springtime, 1971. Inside an office within the Houston Astrodome, a most unusual negotiation is about to take place. Seated at one end of the table is Muhammad Ali, former Heavyweight Champion of the World and self-proclaimed greatest fighter of all time. Next to him: Bob Arum, the former Justice Department attorney turned boxing promoter who had worked with Ali since his 1966 fight with George Chuvalo.

A few minutes later, they are joined by one of the most imposing figures in all of sport, the towering titan of professional basketball Wilt Chamberlain. Ali and Chamberlain knew each other well and had appeared together on numerous occasions in the past, from television talk shows to press conferences addressing civil rights issues. The purpose of this meeting, however, was far different from their previous encounters.

Today no media cameras are present, no reporters scramble for sound bites. The two most famous athletes in the world isolated themselves within the cavernous empty stadium to quietly discuss an event without precedent in the annals of sport. For on this day, Muhammad Ali and Wilt Chamberlain will agree to face each other in a 15-round boxing match, to be held in the Astrodome on July 26, 1971.

For Chamberlain, fighting Ali represented the pinnacle in his quest to conquer not only his own sport, but the entire sporting world.”

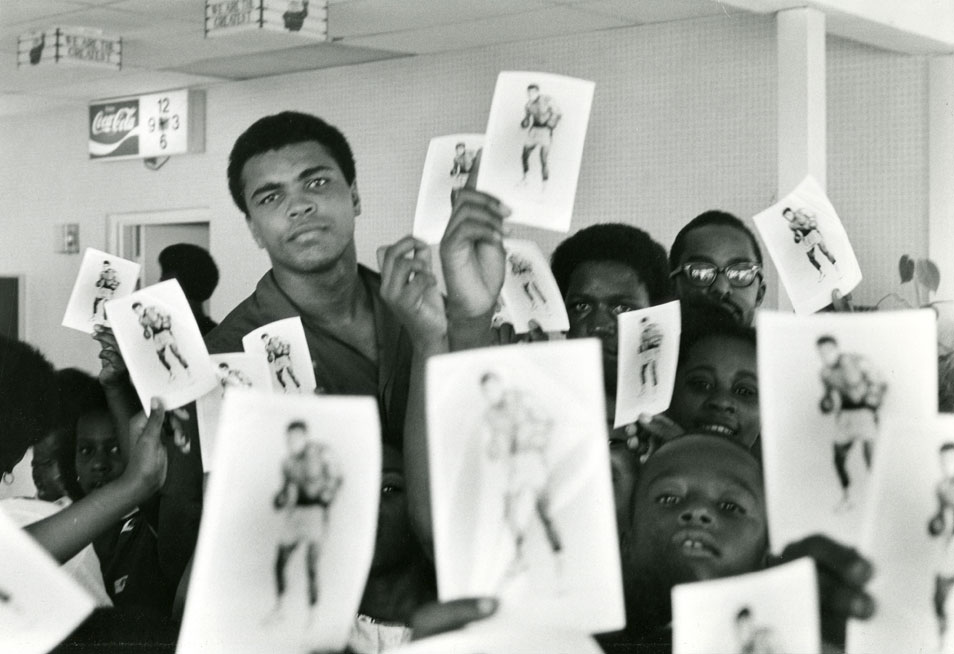

I worshiped Muhammad Ali when I was a child, and I never watched boxing again after he began to slur his speech. There’s a great and heartbreaking Albert Maysles documentary about Ali preparing for his 1980 fight with Larry Holmes–a match that never should have been made. Ali was old, slow and already showing signs of Parkinson’s syndrome, and he was marched into the ring against the best heavyweight in the world at that time. There are moments in the doc (which isn’t online, but is sometimes replayed on ESPN Classics) in which Ali tries to convince himself that he’ll find some way to outwit Holmes–and time itself. But the reflexes and bounce were gone and soon the mystique would be as well. The fight was a travesty and anyone who profiteered from the destruction of a great champion should have had their licenses revoked.

Here a sluggish Ali does the pre-fight promotional shuffle with Merv Griffin:

A piece of Muhammad & Larry:

Tags: Albert Maysles, Larry Holmes, Merv Griffin, Muhammad Ali

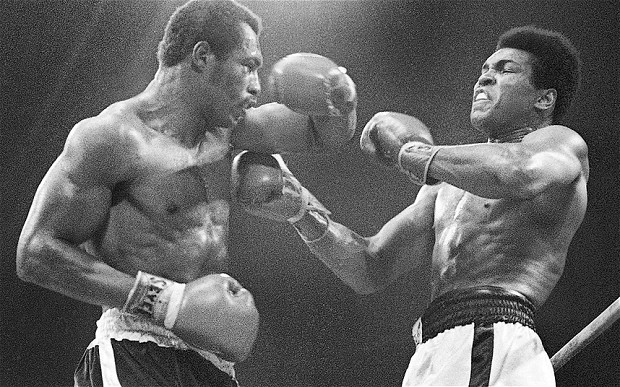

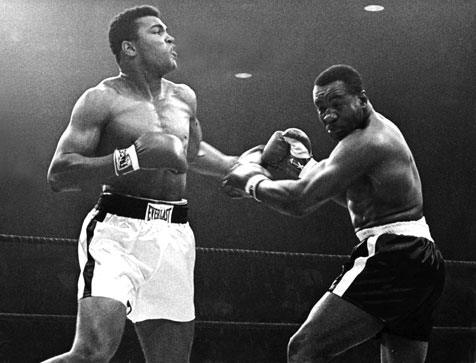

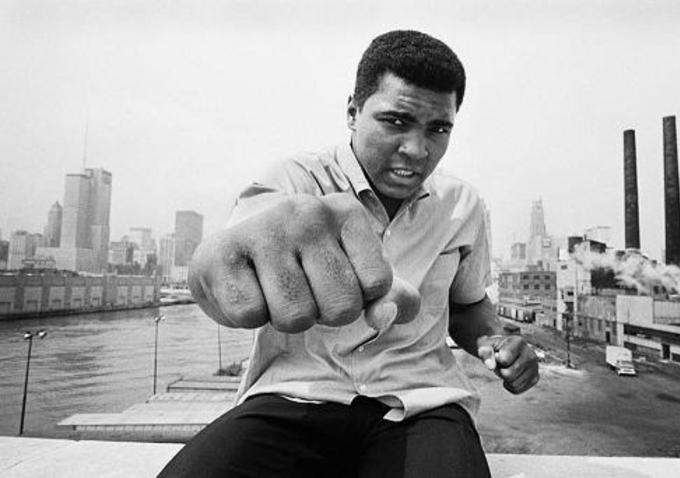

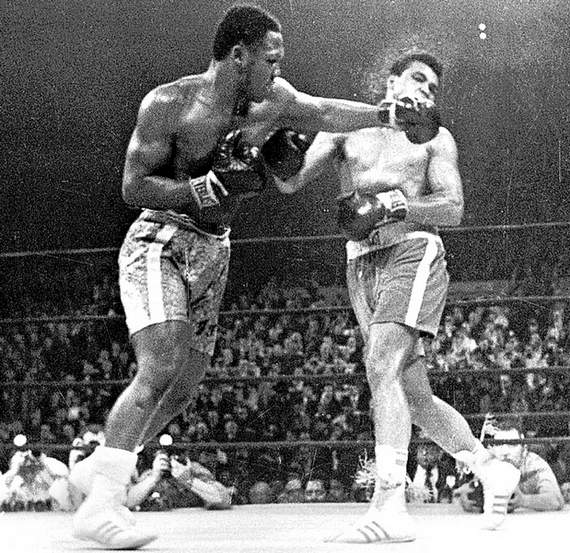

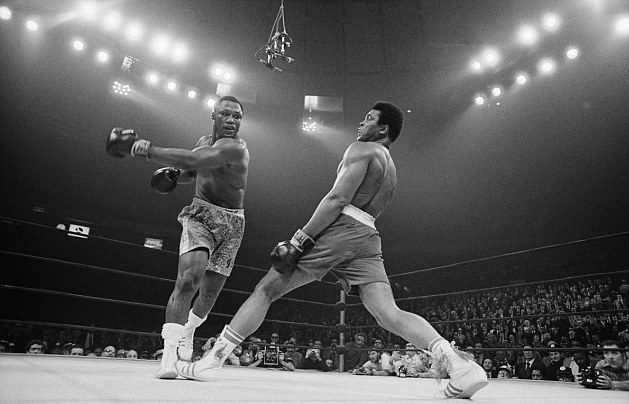

Pete Hamill refers to the evening of the first Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier fight, which took place on March 8, 1971 at Madison Square Garden, as “perhaps the greatest night in the history of New York City.” Maybe. Of course, it would have been amazing to be in Times Square when WWII ended or to hear Abraham Lincoln speak at Cooper Institute in 1860 or to be there in 1927 to watch the ticker-tape parade for Charles Lindbergh after his transatlantic solo flight.

But Ali-Frazier was no doubt very special, considering the political backdrop of the former Cassius Clay being stripped of his title and two of the greatest heavyweights ever meeting while each was still undefeated. Just prior to the fight, Life magazine published a cover story by Thomas Thompson about that anticipated match, “Battle of the Champs.” An excerpt:

There is almost an obscene aura of money hanging over the fight. It might seem to be the ultimate black man’s revenge–each fighter getting his $2.5 million. But the white man will, as per custom, get his. The promoter of the fight is a 40-year-old California theatrical agent and manager named Jerry Perenchio whose clients include Richard Burton, Andy Williams, Johnny Mathis and Henry Mancini.

Perenchio is a pleasant man who wears monogrammed shirts and who would seem to be more at home beside a Beverly Hills swimming pool than at ringside of Madison Square Garden. But he is so far cleverly navigating his way through the turmoil. “I feel like I am smack in the middle of the court of the Borgias,” he said the other day. “So far I am being sued in various lawsuits totaling $58 million, and I have people calling me for tickets–the same people who, before the fight, I couldn’t even get on the telephone.”

The fight will be seen in at least 350 closed-circuit locations in America totaling 1.7 million seats, at prices ranging from $10 per ticket to $30. (Top price at Madison Square Garden is $150, but scalpers are already getting $500 per ticket.) “There’s never been anything like it in my lifetime,” says Perenchio, “very possibly since time began.”

Promoting the fight has not been without its problems. Perenchio simply took the map of America and the world, carved it out into various sections, and set a price tag on each for the closed-circuit rights. If the price was met, the rights were granted. If not, they were withheld. So far, more than 20 auditoriums in the U.S. have been withheld from potential entrepreneurs because of Muhammad Ali’s conviction on draft evasion charges.

The fight will be seen live in Canada, Peru, Argentina, Mexico, Japan, and in England at 4 a.m. There would be considerably more outlets if there were enough time. ‘We only had two months really to promote it,’ complained Perenchio. “We’re like a guy in an orchard with only a limited amount of time to pick the fruit. We can only get at the lower branches.”

Perenchio is not overlooking any way to make money from the event. Besides the expected $20 million to $30 million gross anticipated from the fight itself, he is selling the rights to the souvenir program, between-rounds commercials, a special poster and post-fight movie–to be delayed for six months–for a total of $4 million. “We haven’t sold it yet, in fact we’ve only had a few offers of $500,000 or $250,000. We just don’t want to schlock it.”

On top of all this, Perenchio actually plans to seize both boxers’ trunks and gloves so that he can auction them off later. “If they can sell Judy Garland’s red Oz shoes for $15,000, then we should get at least as much for these,” he said. “We get a little blood on the trunks, it makes them all the more valuable.”•

Tags: Joe Frazier, Muhammad Ali, Pete Hamill, Thomas Thompson

Life is a fight that’s long and bruising, the score changes regularly yet surprisingly, and no one really wins in the end. And that’s for the fortunate ones. When we’re at our best or worst, it seems like it will go on forever, that no fall or rise is possible. But the sands shift and the tides are unimpressed. We can spend our time marking down who’s leading, but we’re all falling behind.

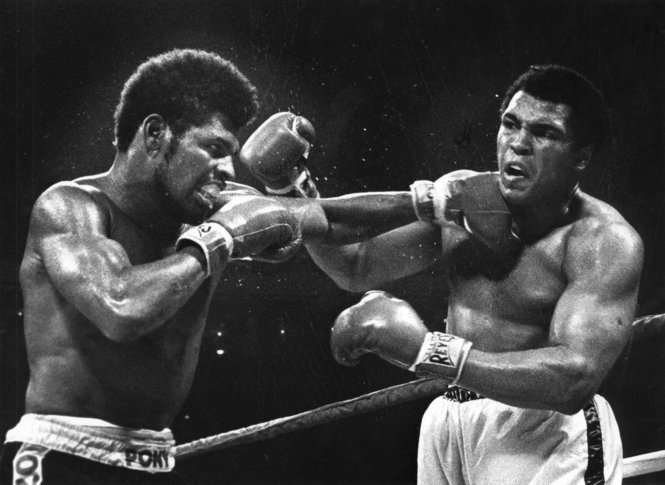

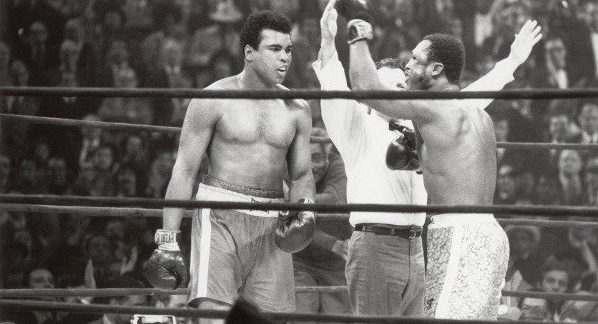

Two fighters, Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, brought out the best and worst in one another. Their three fights in the early 1970s made them legends and made them old. Ali used ugly, racist words to describe his fiercest opponent. It was the Greatest at his lowest. Frazier relished Ali’s eventual physical decline, diminishing himself in the process. They were both winners, but it wasn’t enough–the other had to lose. Ali seemed better about letting go of the feud in later years, but let’s remember that he won two of the fights. From “The Lonesome Death of Smokin’ Joe Frazier,” Tom Junod’s 2011 Esquire piece about the rivalry that couldn’t end on its own terms:

“The only time I ever met Joe Frazier was in downtown Atlanta, outside the arena used as a boxing venue during the 1996 Summer Olympics. The week before, Ali had once again “shocked the world” when he was handed the torch at the opening ceremonies, and then he elicited both pity and awe when he shakily climbed the stairs and ignited the Olympic flame. Despite winning the gold medal in the 1964 Games, Joe wasn’t invited to the stadium that night, and now he was selling T-shirts in a jerryrigged shack outside the boxing arena, just another of the carnie barkers who infested downtown during the games and turned Atlanta into an eyesore. His son Marvis — the former heavyweight contender who had been knocked out as if by a gunshot by a Larry Holmes right hand and then almost killed by Mike Tyson — was working the shack, making change. ‘Hey Joe!’ I said, and walked up to him as my father had 25 years earlier. He held out his hand horizontally, and held it still. ‘Hey Joe!’ I repeated, and Joe, looking at his hand and then at me, said with a familiar smile: ‘Still steady.’

He was saying that he had won. He was saying that while Ali was a rattling relic with Parkinson’s Syndrome, he, Joe Frazier, was still steady, and capable of keeping his hand still. He was saying, above all, that wherever Ali was, he, Joe Frazier, put him there, and that he was vindicated by the split decision handed down by the fullness of time.

Now Joe Frazier is dead, and Muhammad Ali has once again miraculously outlasted him. But that’s the thing about fighting your battles over the fullness of time: You fight when you’re a young man, and you fight until the final bell. You keep fighting when you’re an old man, and you keep fighting to the death.”

Tags: Joe Frazier, Muhammad Ali, Tom Junod

It’s difficult to think of another American who had a life just like Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry, better known as polarizing comedian Stepin Fetchit. Born in 1902, Perry used a stereotypical lazy-man persona to become the first black actor to reach millionaire status. History hasn’t been kind to his screen character, as blacks and whites alike came in time to see it as degrading. But Perry felt otherwise; he believed it was a means to an end. He thought that his on-screen buffoonery, stereotypical as it was, transformed the popular perception of a black man in America from one of a fearsome or predatory figure to that of a lovable clown. And he felt he paved the way for other people of color to become screen stars who didn’t have to play the fool. Perhaps he’s right, though it’s still incredibly painful to watch. Perry became a lightning rod for criticism during the Black Power movement of the 1960s but never backed away from his beliefs.

A tangent: When he was young, Perry was friends with embattled boxer Jack Johnson. (They must have been quite the pair–the fighter who enjoyed making whites nervous and the entertainer who wanted to reassure them.) After he joined the Nation of Islam during the 1960s, Perry supposedly taught Johnson’s “anchor punch” to another controversial African-American heavyweight, Muhammad Ali. The Greatest used the maneuver to defeat Sonny Liston in their second fight. At the 8:00 mark of this passage from the 1970 documentary A.K.A. Cassius Clay, Perry and Ali ham it up for reporters.

Another Perry tangent, this one horribly tragic: His disturbed son, Donald Lambright, who used his stepfather’s name, committed what appeared to be a number of racially motivated murders. From the April 7, 1969 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette:

Johnson said Lambright slept with a .30-caliber rifle in his bed.

‘Donald said he needed protection from whites,’ Johnson said. ‘He was paranoiac at the time.’

Johnson said Lambright was friendly with many black militant leaders and was a member of the Republic of New Africa, a black separatist organization.

‘Donald thought he had the answers to a lot of problems. And he felt the only way some of them could be resolved would be through violent action.’

At 9:14 a.m. yesterday, state police said, Lambright and his wife entered the Pennsylvania Turnpike where it crosses the Delaware River from New Jersey.

About 45 minutes later, Lambright began shooting.

Witnesses said most of the firing was done as he drove along, slowly weaving from lane to lane. They said he fired into eastbound traffic. Now and then he pulled over and fired from the roadside.•

Tags: Donald Lambright, Lincoln Perry, Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry, Muhammad Ali, Stepin Fetchit

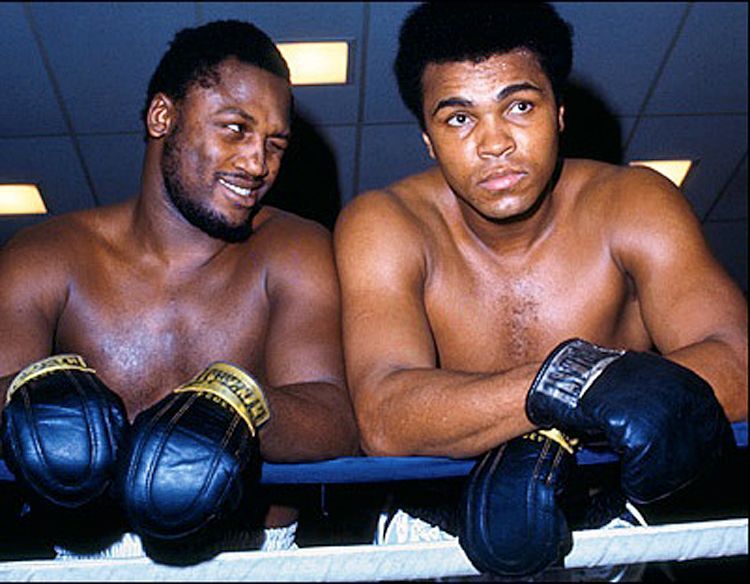

Muhammad Ali just made an appearance in London for the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games. Here’s footage from another Ali jaunt to that great city, when he recorded a special 1974 interview program. The boxer and activist was diminished physically at this point, mostly due to two titanic bouts with Joe Frazier. Neither fighter was ever the same again.

Tags: Joe Frazier, Muhammad Ali

I think Muhammad Ali in his prime would have beaten Joe Louis in his. But legendary trainer Cus D’Amato, who was still to mentor Mike Tyson down the line, argued in favor of the “Brown Bomber” when he and Ali debated the point in 1970, during the uncrowned champ’s Vietnam Era walkabout.

Tags: Cus D'Amato, Muhammad Ali

While Muhammad Ali was exiled in his own country over his refusal to perform military service in Vietnam, he “boxed” retired great Rocky Marciano in a fictional contest that was decided by a computer. Dubbed the “Super Fight,” it took place in 1970. The fighters acted out the computer prognostications and the filmed result was released in theaters. Marciano summed up this moment of Singularity the best: “I’m glad you’ve got a computer being the man that makes the decision.” A piece of the film:

Tags: Muhammad Ali, Rocky Marciano

Looking back to an odd incident from 1981, as “The Greatest” turns 70.

Tags: Muhammad Ali, Walter Cronite